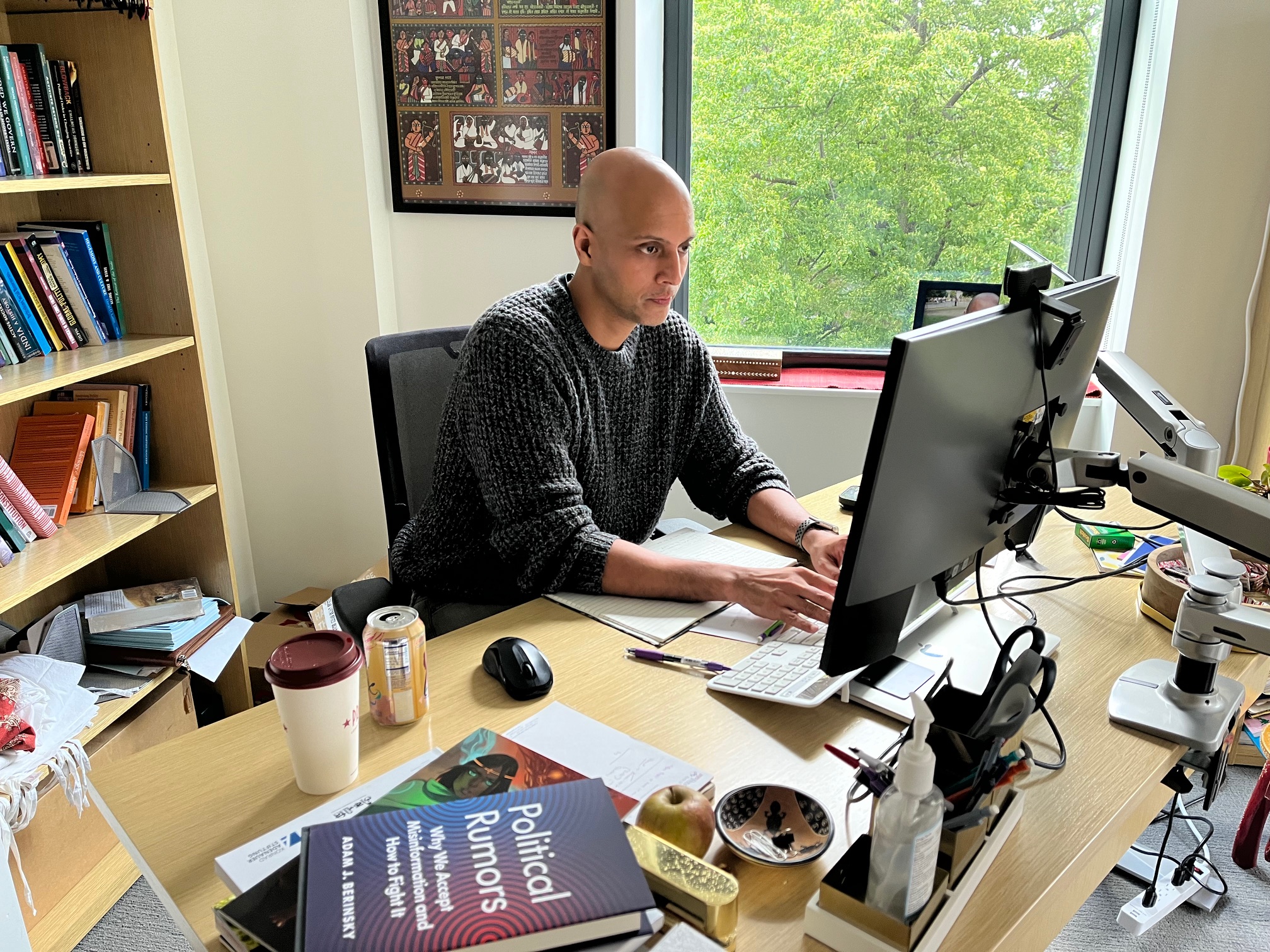

CASI Deep Dive: Tariq Thachil on CASI and the Complex Challenge of Studying India in the United States

Tariq Thachil took over as Director of the Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI) at the University of Pennsylvania in July 2020, just as the world was grappling with the uncertainty of a global pandemic. He steps down in June 2025, at a time when American academia faces a new wave of pressure—from funding challenges to deepening questions about the role of international students and academic freedom. Thachil’s five-year tenure may have been bookended by crises, but it was also marked by a surge of interest in India—an era that CASI was uniquely positioned to navigate and shape.

What did it mean to steer CASI through this moment? How has the growing attention on India—from donors, students, and the public—reshaped the role of a university-based India center? Why is there such a disconnect between how India is studied in the U.S. and the questions that matter within India itself? And what lies ahead for future leaders of institutions like CASI?

CASI Managing Editor Rohan Venkat sat down with Thachil to discuss building research bridges between India and the U.S., why American political science can sometimes miss the mark on India, and how running a center like CASI has become a far more complex—and consequential—task.

Rohan: Tell us about your pathway to CASI.

Tariq: My path to CASI began when I came to CASI as a graduate student and found it to be quite refreshing. As a political scientist, I had not been in a space like CASI. I felt like I had a divided life between an “area studies” community in which there were very few political scientists, and a disciplinary community where there was really not that much focus on India. I'd often be the only India scholar in the room. CASI was one of the few places where everybody was focused on discussing India, but there were also many from either my discipline or adjacent disciplines.

Ever since then, I have been very enmeshed with CASI. At different stages of my career, I came back—as a junior faculty member, as a tenured faculty member, to present, to participate in workshops, etc. From very early on, I had the feeling that it was a unique space, and so I was very excited about the possibility of being part of that space as director when the opportunity came up.

Rohan: Just to understand, what made it unique to you?

Tariq: Two things. One, a lot of the typical venues where somebody who works on India or South Asia got an interdisciplinary area studies engagement in the US were at places like the Madison South Asia conference, or even going to other South Asia centers, which were very valuable for me. But those centers really are dominated by particular disciplines—history, anthropology, etc. This is not about assigning blame, but fields like political science, economics were very underrepresented in those fora. CASI was really the only place where I could see a blending of people who were from disciplines that were adjacent to mine in the social sciences, but were fundamentally interested in India. The Center also encouraged you to frame your research, and provided feedback with a sharper emphasis on connecting to debates and discussions happening within India, and not simply in the American academy.

That was different from what I had experienced in the US at either South Asia centers, on the one hand, or within my discipline, on the other. It was intellectually unique. And that made me feel attracted to the idea of directing CASI, because I did see it as a space that spoke to my interests in cultivating both social scientists who really put India front and center when thinking about their projects, but also Indologists who were interdisciplinary.

Rohan: What did you see as your task when you took over?

Tariq: My first response is a somewhat prosaic one, but one of vital importance when thinking about academic centers. CASI, for all its successes, was not very financially stable when I came in. And honestly, the first task was the unglamorous work of making it financially stable, which was especially difficult in 2020, at the outset of the budgetary uncertainties imposed by the pandemic. The second: CASI’s prior directors had done an amazing job of fostering policy-oriented conversations both in India and about India in the US, especially with respect to India’s political economy. I wanted to preserve that, but also broaden CASI even further as an interdisciplinary space to include contemporary historians, anthropologists, sociologists. It's not that CASI had had no interactions with those disciplines, but I wanted to increase the proportion and space being given to them, and the scope of collaboration that CASI engaged in and supported across a wider swath of the university.

Then, organizationally, I wanted to institutionalize CASI. As with many centers in their earlier days, CASI had relied on a lot of transient populations—visiting fellows and part-time researchers. I wanted to build up the everyday research capacity at CASI, among both faculty and non-faculty. We still have lots of people who are visiting and coming through, including yourself, but putting a faculty associate director in place as a permanent appointment, expanding our postdoctoral program from one fellow to three, starting a pre-doc program, expanding the number of PhD fellows—all of those things increased the everyday “peopling” of the Center.

Tariq Thachil in conversation with filmmaker Mira Nair (2023 Saluja Global Fellow Lecture)

Rohan: I want to ask about the broader environment over the course of your tenure. You started off during Covid, and you’re ending just as some fundamental questions are being asked about academia in the US. How did that impact what you set out to do?

Tariq: I took over at the apex of the onset of Covid. For me, that meant learning how to do a new job at the time that the job itself was fundamentally different. To run an India center where you couldn't bring people from India, you couldn't send people to India—students or faculty—you couldn't really do research in India...a lot of our research, which relies on interactions with human subjects, was not ethically possible at the time. A lot of the core activities of CASI couldn't happen.

An underappreciated negative was that a lot of centers, including ours, depend on fundraising, which was uniquely difficult to do during the pandemic—not to mention, it was such a difficult time in India. As a center you're trying to figure out a way to contribute or have events that shine a light on what's happening in India during the pandemic, but at a time where you also feel very painfully disconnected because you're not there. That was an intellectual challenge.

One way we tried to address this challenge was by moving to a fully virtual platform for all our events, which allowed us to showcase a lot of voices within India. A very high proportion of our webinars from that time featured scholars and practitioners from India, which budgetarily we're not otherwise able to do. Also, a lot of our audience for those events came from India. One of my favorite things was how hungry people were for scholarly content at the time.

We had a lot of students signing on, not just from the elite universities of India, but also regional universities. They would write to me afterwards saying, "We never thought that we'd be able to attend a University of Pennsylvania event or an Ivy League event and hear from this speaker or that speaker, and even ask a question." That part stayed with me and is the main reason we've maintained at least some virtual programming post-pandemic.

It was a difficult moment, but it also provided opportunities to force us to reorient. Even with India in Transition, our bi-weekly publication, which you edit, we conducted a review during the pandemic and found that the Hindi IiT page was actually the most visited part of our website—which was surprising to all of us—and forced us to rethink our assumptions about who our audience was. That was when we increased the number of translated languages that we published in IiT—not just in Hindi, as we did before, but also into Bengali and Tamil.

While I came into CASI at a challenging time, the current moment is, to me, a much more pernicious and precarious one. Covid was a universally shared challenge. Right now, universities in the U.S., including Penn, are being specifically targeted and constrained. Not just CASI, but all centers are going to have to reckon with how to navigate this moment in terms of making decisions about the preservation of academic freedoms, the pragmatics of protecting the students and faculty and intellectual communities that you house and support, and the budgetary uncertainties staring us all in the face. None of these decisions are simple, and the implications of any decision are complex. That's one of the things that I've learned in this job. It's all very well to take particular strong lines, but often you, as the director, a tenured professor, will not pay the consequences for drawing those lines. It'll be international students affiliated with you on visas or staff members or contingent faculty, or even staff working internationally, who will bear the brunt of any fallout.

How do you navigate these decisions, not just with your own personal reputation in mind, but all the interconnected and often more vulnerable people who are associated with and supported by the center? The importance of navigating such thorny questions will only be ratcheted up. So yes, my five years at CASI have been bookended with these two very different kinds of challenges. Without minimizing the trauma of the global pandemic, it is fair to say from the specific perspective of academic centers like CASI, I feel more troubled about this current moment than I did in 2020.

Tariq sharing a collaborative moment with Senior Visiting Scholar Adam Ziegfeld during a CASI workshop.

Rohan: There’s an interesting contrast there, because even as this period has had its difficulties, it has also been a time when interest in India in academic circles has gone up. There seems to be more money, more donors, more India centers popping up. You said there were not many places like CASI when you were younger. Is that changing?

Tariq: Yes. There are opportunities now that were just not available even 10 years ago, let alone 15 or 20 years ago. It's worth acknowledging that. There are many more centers devoted to the study of not just South Asia, but India specifically. CASI was the first such center at a US university, but there are other India initiatives or India-focused centers that have been set up now. That is its own interesting intellectual phenomenon, because a lot of the support for such centers really seek to identify India as its own source, really not wanting to support a center that is largely about South Asia and whatever that means as a regional idea. That current has only grown over time. A lot of the support, a lot of the donor money is really interested in de-hyphenating India from South Asia and thinking about it as its own country for study. While CASI, in many ways, spearheaded the idea of an “India Center,” I have concerns about this larger effort to separate the study of India, especially at a time when collaborative thinking and engagement within the region of South Asia feels as urgent than ever.

With respect to this rising interest in India, it’s not just among donors and alumni, but also current students. The number of students who I have, for example, taking my class—democracy and development in India—which I have taught a version of for almost 20 years now, has gone way up. The proportion of students I have who are non-Indian or not of Indian heritage has also gone way up. It's over half of the class now. When I started teaching at Yale in 2009, only about 20 percent of the class was non-Indian or non-Indian heritage students. So, the change is not just among donors and alumni, but among students. And even in the intellectual environment of the US in general, interest in India has gone up. That offers an important opportunity for centers like CASI to secure support, visibility, to expand and support research, to increase faculty hiring on India. That's all to the good.

Even as we no longer suffer from the problem of irrelevance—just shouting to have India be considered relevant as an object of study for the university—the concern now shifts to being more careful and judicious with the support that you're going to take, or not take. In terms of fundraising, there might be a lot of interest in funding a center on India. But what are the imperatives of donors? Earlier we struggled to find any donors. Now you may have multiple people who are interested, but it is important to be very clear about the motivations for that support. Will there be explicit or implicit pressures for the center—in sharing its programming, its research activities, its ability to remain impartial or even critical in its commentary?

Beyond such concerns about intellectual freedom, there is also often a misconception among donor communities about the role of academic centers like CASI. Often, the desire is for them to function like a think tank like Brookings or Carnegie; having lots of glitzy, high-profile events that are on the circuit of India hands and foreign policy communities. In my opinion, that is really not the comparative advantage of places like CASI. We are, first and foremost, a university-based academic center. Which means our mission should be centrally about conducting deep research, fostering new generations of scholars, and educating students—none of which are in the wheelhouse of think tanks. So, part of my job is to both explain this difference as well as convince this newly infused class of donors that it is worth pursuing and supporting.

Rohan: To then focus on the research side, I’ll draw you back to a piece you wrote with Milan Vaishnav right before you came into this role, entitled “The Strategic and Moral Imperatives of Local Engagement: Reflections on India.” This also connects with a few things that a previous CASI director, Devesh Kapur, wrote in an IiT article as he was leaving this position, titled “The Study of India in the United States.” Before I ask you to reflect on those thoughts, what was your argument in the piece?

Tariq: Devesh’s piece and ours were making distinct arguments, but they were both jointly motivated by developments in some social science disciplines, primarily economics and political science. Increasingly, the kind of work we were seeing being done on India in these fields was in service of the disciplinary imperatives of, in our case, US-based political science, and often at a remove from the big questions animating scholars working in India. Just to give you one example, which was true in 2018 and I think sadly is still true. If we think of the dominant electoral phenomenon in India today, it's been the rise to dominance of the BJP and the leadership of Narendra Modi. I don't think US-based political science, absent maybe one or two pieces, has had anything especially useful to say about that. I'd be hard pressed to find a book coming out of the US that offers us a great explanation of what might be the most significant political development in India in the past decade.

On the other hand, we've had a proliferation of studies of the working of local democracy, of the workings of affirmative action quotas, and the functioning of local governments, which is very important. I, myself, have worked on local urban politics during this time. But if you were reading US-based political science on India during the past decade, you would come away thinking this has been an era of unprecedented decentralization, devolution of power, and that the most important tier of government in India is local government, and the most significant political issue is that of caste and gender quotas. Yet much of what we know from scholarship and policy-oriented writing from India itself suggests the country has experienced considerable political centralization. And while affirmative action is no doubt important, the focus it receives is disproportionate to its importance, simply because it is an issue amenable to establishing causality. After my first book, on the rise of the BJP pre-Modi came out, I remember a senior scholar in my department telling me I should really focus my future work on gender quotas, because they are randomly assigned! That's the kind of disconnect we were talking about.

Rohan: Where does that disconnect come from? Is it just the gestational period of academia? Is it the interests of academics trying to conform to the US academy?

Tariq: I think conformity plays a big role, and in our disciplines, a big driver of conformity comes from particular methodological trends. The imperatives of positivist social science in political science and economics, the attention to causal inference, has elevated the study of certain questions, and sidelined others. I'm not quite as critical as I think Devesh was in his piece about this development. I think there are lots of merits to that form of scholarship, and useful things to learn from it. But I do agree that there have been considerable costs to the increasing homogeneity in our fields in terms of what we study, the kind of work that is valued and that will get you jobs, get you tenure. The strategic incentives to produce research have pushed it in the direction of very micro-level work, and thematic areas that lend themselves to particular methodological techniques. There is no doubt creative work being done, but I do feel it has led to only being able to ask certain kinds of questions and completely ignoring others.

I don't think it's that scholars in the US are unaware of these other political phenomena or economic phenomena that might be of interest. But they don't see it as strategically feasible to work on those topics and publish in the kinds of journals that they need to, in order to have successful careers in the US. The chances that you can get tenure in a top department in the US working on India, certainly in my discipline of political science, and produce work that is of interest to a broad community in India has become more difficult.

Maybe the biggest place where I see that is in teaching. A lot of the pieces that our community writes, we don't actually teach to undergraduates or it's difficult to teach it to them in an India class. When I'm looking to have these readings that summarize big developments in India on a given topic, it's typically not peer-reviewed journal articles coming out of US political science or economics departments that I'm assigning. And that wasn't as true one or two generations ago. A lot of the top scholars working on these topics were writing the pieces that we could assign to students back then.

Now, of course, something has been gained in terms of the precision, the kinds of data and empirical evidence that we have access to and are generating. There is a lot of valuable stuff that has come out of these intellectual trends, but something has been lost as well. And that was what was motivating the hope of a corrective that Milan and I were talking about.

Rohan: How are those two trends interacting? From the outside, one might imagine the proliferation of India centers and the student interest in India might counteract the built-in expectations of American academia, allowing scholars to focus on things of more interest to those in the country. But actually, the rise of interest in India has not been such a big phenomenon that it can upend more structural trends in your disciplines.

Tariq: I think that's right. We have to be very humble running a modest-sized regional study center. We are not going to change career incentives and the academy. But what we can do, what CASI has tried to do and definitely something that I have tried to do, following that piece with Milan, is to offer scholars in the US—who are dedicating their lives to understanding and studying India—the kind of feedback that might embed their research more firmly within the communities they study. One question I ask scholars is whether they seek and receive any criticism or constructive commentary on their work from a room full of people who know India really well.

You've attended the political economy workshop that CASI runs. The scholars who attend are people who will get a lot of comments on the best methods to use and the best models to run from lots of different audiences. But perhaps CASI is one of the few venues where they will get 35 people in the room, all of whom know India well. People who can say "Well, here is a problem with that data source," or "Here is somebody who's working on that in a university in India who you might connect with," or "We don't know whether we would actually use that term, which is a Western framing that will not resonate with India audiences for these reasons.”

If we are optimistic about the potential for such conversations, there is a role for centers like CASI to curate communities that will provide that kind of engagement. And to do so for disciplines like political science and economics, for which this problem might be most acute.

But the role of such a community can be even broader, which is to foster a wide interdisciplinary community where every week you are engaging with a speaker from a very different disciplinary background. Interdisciplinarity is one of the most overused terms in academia. It's celebrated by almost everyone, but practiced by very few.I can say that now with some authority after directing CASI. You can say you champion interdisciplinarity, but almost always, it is anthropologists who come to the anthropology talk, economists come to the economist talk, and relatively rarely do they come to each other’s talks.

But if you can create a community where such cross-field interactions do happen and you actually do the work of coming every week to engage with people on their terms from different disciplines, there is real learning to be had that might also influence the way you do research. Our pitch is that even if you are narrowly concerned with your career, you might actually do better and more creative work even within your discipline. So, there is a strategic incentive that you might actually come out with something and an idea and an approach that distinguishes you from the 20 other people who are doing a version of what you are doing. Because with that increasing conformity, there's also increasing homogeneity. And so, this might actually be a way to foster a comparative advantage if you're willing to put in the work.

Tariq listening to vocalist Shubha Mudgal (2025 Saluja Global Fellow) as she speaks to Penn students.

Rohan: The idea of the Center as being, in some ways, an interdisciplinary counterweight to the department, perhaps?

Tariq: Exactly. Especially for junior scholars, I think that the department and the “discipline,” in the Foucaultian sense, weighs heavily on you. Understandably so. And I don't think we're trying to disrupt that. People have to get jobs and make their careers. But I think we are providing a little oxygen so that you have other voices in your head, so that you can still be aware of a broader conversation in which your work is being situated. And maybe it gets you to make the marginal effort: you write a piece for India in Transition and an audience beyond your discipline, or for an interdisciplinary community. Even just the act of coming to give a talk at CASI, we tell every speaker, “This will be an interdisciplinary audience, there will be maybe only 20 percent from your discipline.” I've seen people have to then frame their talks differently and make them more accessible, less reliant on jargon, less narrowly embedded within specific literature. And even that is an intellectual exercise that is useful for everybody to do.

An anthropologist may lean in more into their ethnography when talking at CASI because they know that that may be the most accessible to an interdisciplinary audience. An economist may actually shorten their fifty-thousand slides showing the robustness of their study design and spend more time situating the larger phenomenon they're trying to study. There is value in that. And again, we're trying to be humble about how much this can do, but just being known as that kind of space, even for people early in their career, is valuable.

And then for people who are more senior, the idea is to provide a space to say, "Well, you're now at a stage where you can afford to maybe take more risks, embed yourself in a community that asks questions a little bit differently than what your discipline demanded." But even if you decide to do that, where do you look to for models of people who have done that? And one place might be to look up the events list of CASI and see—"okay, who are the senior scholars who came there?" Typically, we try and invite those people who we think are making that effort.

Rohan: You've covered, to my mind, two elements of what you laid out in that paper with Milan. But there’s a third that you also discussed in an interview with Penn Today as you were starting off at CASI. And this is the importance of taking your research back to India and connecting to the research community back there.

Tariq: That is super important. The point we made was that engagement with local communities in India should be both for strategic and what we call, for lack of a better term, moral reasons. Strategic in the sense that we actually think it makes your work better. If you're not getting your work vetted by Indian communities, you could make very, very fundamental errors, like using the wrong phrase or the wrong translation for a key concept in a survey. Or the use of data sets that seem great, but which a lot of local journalists, scholars, or policymakers will point out have many problems. So, there are strategic reasons for more rigorous scholarship. We define rigorous often in very truncated ways, but part of “rigor” is actually having work vetted by the communities you're purporting to study.

The “moral” reason we note is, are you actually asking questions that are of importance to people in India? Sometimes you could have a very rigorous paper on something that a local community finds utterly trivial. It is useful to actually face that music in the hope that it would influence you in the future to do better.

In the piece that I wrote with Milan, it was a lot about us sharing our work in India and getting feedback. But my thinking with CASI has made me realize that the number one thing we can do is provide our resources and platform for voices within India to connect with scholars—in the US, but also with others from different academic communities in India. CASI's role in that has been twofold. One, we curate academic events in India for academics and scholars to present their work, and usually those feature predominantly India-based academics. That's really important, to showcase voices of all the terrific work that's being done in India, not just helicoptering in as Ivy League professors to share our findings with an India-based audience.

The second is bringing people to Penn and to CASI. To really think, what would make a meaningful opportunity for not just an academic but a journalist, a policy maker, a practitioner? How can we offer them value in taking time out of their busy lives in India to come to a place like CASI and Penn? A lot of it is to give people time and space to have thoughts and develop projects that the daily grind prevents, and also to integrate within a broader network at Penn, go and give talks at other places in the US, and then use CASI as a space to facilitate that. Those two things are different ways in which we work with intellectual communities in India. Having them come and populate our Center also provides some of the engagement that we were talking about earlier, as does showcasing those voices in India. Those have been the two pillars of what CASI has been trying to do. One great example was hosting the data journalist Rukmini S., who is a mutual friend of ours, during a time when she was conceiving and beginning to execute a fantastic new initiative, Data for India. I think being at CASI gave her both time and space to work on that idea, as well as opportunities to get input from scholars and practitioners at a formative time. She, in turn, helped organize and curate a hugely successful data webinar series for us, featuring a lot of folks from India to whom we had not previously given a platform.

Tariq and CASI Non-Resident Scholar Adam Auerbach display their co-authored book, Migrants and Machine Politics (Princeton University Press, 2023).

Rohan: We talked about what’s happening in the US to academia. What is happening in India, too, is relevant. On one hand, there seem to be more universities and centers showing up, attempting to take their work to a wider audience—and to keep talent in the country. On the other, there are key questions of both academic freedom but also the complex incentives of returning/staying in Indian academia, something that another CASI hand, Neelanjan Sircar, has occasionally talked about.

Tariq: We're in a moment where there are different challenges in both countries that CASI is situated between. We already spoke about the challenges in the US right now, and those are newly salient. But the challenges in India have been apparent for some time, and intersect with CASI in a couple of different ways.

We all know of the significant and growing constraints on critical and open intellectual inquiry for academics and research communities in India, in particular, in the fields we work in and the topics we work on. Centers in the US are not immune from such duress, especially in the age of social media.

Previously, a lot of what these centers like CASI did was only locally visible. I have talked to former directors about this. When they were running CASI, very few people outside of CASI, let alone Philadelphia, knew what was happening at the Center. That is no longer true. Whatever we do is known everywhere, including in India. And that is both an opportunity for engagement and it's also a challenge. Because any larger controversy that not just CASI, but a given speaker might be enmeshed in, now has a much higher potential to become inflamed. Navigating those currents, again bearing in mind all the different constituencies that depend on CASI at Penn and in India, therefore becomes all the more difficult.

These pressures also intersect with the new currents in the US in strange ways. One example is the study of caste. Speakers who talk on the issue of caste come from a range of different perspectives. There are demographers and sociologists working on compositional or occupational shifts within caste populations, political scientists working on changes in caste voting, or scholars within the critical caste studies tradition. Yet often when we have a speaker whose talk has caste in the title, we receive criticism from within both the U.S. and India, an odd email asking, "Why are you platforming conversations on this divisive issue?" These voices often echo a growing strain of commentary within the Indian diaspora in the US, echoing particular narratives in India, that sees any discussion of caste as inherently divisive and unnecessary. Interestingly, we now also hear some eerily similar echoes from “anti-DEI” voices within the U.S. who see discussions on caste as troubling illustrations of an overemphasis on questions of diversity, inequity, and inclusion.

This example illustrates the challenge. For me, it is impossible to imagine running an India center without curating substantive discussions on caste, but that is an issue that is now in the sight lines of powerful communities in both the US and India. To me, this should not result in us shying away from these conversations, but it does signal the increasing difficulties in preserving spaces for these discussions. These challenges were more significant for me than for past directors of CASI, and I think will be even more significant still for the next director. They will have to manage walking the fine line of preserving space for open discussion while maintaining all the different elements needed for the institution to survive and thrive. All I can say is that I don't think there's any magic formula for doing so. It has to be a careful, considered set of decisions. But it is over a terrain that is increasingly tricky.

Rohan: For me, that brings up the question—to your mind, what is the role of an India center at a US university? And how is that different from a think tank, or the department, or policy advocacy and so on?

Tariq: I think university centers like ours are really foundationally about research, and supporting research. Ideally, first and foremost, supporting the research of younger scholars. We've talked about all these different challenges for academics. But the people who face all these challenges most acutely are graduate students, PhDs, postdocs, who are trying to make a career and facing all of the currents we've talked about, but in extremely vulnerable stages of their life. What can a center like CASI do to support their work?

At the same time, in supporting young researchers, what can a center like CASI do to promote certain kinds of research from US scholars that is embedded in India? Because in India, your research will necessarily be embedded in the country and conversations happening within it. But in the US, there's a real danger that the research on India can increasingly become disconnected, for reasons we spoke about.

What can CASI do? It can select and promote scholars, especially younger scholars, who are not swimming against disciplinary currents, but are really trying to do their best to be as embedded in India, even when it may not always be their most straightforward career incentive. We can provide at least some of those career incentives by giving them postdoctoral fellowships, or graduate fellowships, or space to publish in India in Transition, or come and give a talk, or be invited to our workshops—showcasing their work and saying that these are the kinds of people that we want to support.

For example, we have three postdocs. We have an informal rule to have them from different disciplines, and to pick people who are doing work that we see is deeply attentive to context and speaks to the interests of scholars beyond their discipline. Sometimes those kinds of contextually embedded, interdisciplinary scholars fall through the cracks of traditional department hiring. So, can we be a space that provides at least some support and platform for that kind of work? I think that, first and foremost, is our mission, to help shape the intellectual currents in the US around the study of India in ways that are productive. And for me that means work that is deeply embedded in India. It can go in many different directions, but it is really rooted in deep connections and time spent and engagement with India and intellectual communities in India.

Tariq flanked by former CASI Directors Devesh Kapur and Marshall M. Bouton

Rohan: In the 2018 paper, you mentioned that some of these elements are specific to India, because it is large, and has a lot of anglophone research. I’m curious, as head of CASI, did you have a chance to draw from experiences of the leaders of centers or equivalent institutions focused on other geographies?

Tariq: I absolutely have. I think one distinctive feature about India relative to many other geographic areas, and especially other low-income countries, is the surfeit of younger scholars working on India in US universities, who are from India. As one observation specific to my own discipline, I'm in the process of doing a review of research on India published in US political science journals since the 1960s. One trend I can already see is that a lot of the early scholarship in the field was being done by non-Indian scholars, who also held a lot of the senior, faculty positions in leading universities. And they did lots of good work—so this is not a narrow argument about identity credentialing.

But it has been heartening to see the increasing representation of political scientists from India in US-based academic research on India. And this has also shaped the kind of work they can do, as many of these scholars come into graduate school with language skills, and have personal experiences in India. Of course, there remain significant limitations to this trend, most notably that those coming from India are from highly elite class and caste backgrounds. In fact, CASI’s predoctoral program, which I established, hopes to address this issue in a modest way by emphasizing the selection of underrepresented students from India to come to CASI to work as research assistants, and get help in applying to US PhD programs.

That said, even the limited representation of scholars from India we see is not true of other regions. Take, for example, the study of the region that in the US is referred to as “sub-Saharan Africa,” where there really isn't that kind of pipeline of scholars from the region. Or even other South Asian countries, there's a much smaller pipeline of scholars coming from Pakistan, even smaller still coming from Bangladesh or Sri Lanka. There’s no one country from sub-Saharan Africa that quite dominates faculty positions in the same way as India does for South Asia. And that's also true for Latin America. And that dominance can perversely crowd out the potential for growing the study of non-Indian South Asian countries. This is especially true if departments in the US continue to regard one faculty member from South Asia as sufficient, which has often been true even at the well-resourced universities in which I have spent my career. Compared to other regions, such as Latin America, there remains a far lower appetite for multiple hires of faculty working on South Asia. In such a constrained setting, the scope for hiring South Asianists working outside India remains limited.

Rohan: What do you think most people get wrong about having to run a center like this? What are the misconceptions that you have to face frequently, from donors, students and so on?

Tariq: From donors, the misconception is what an academic center is. In particular, a big misconception among donors is that the central life of our kinds of centers are high profile events. Or platforming government officials. Or having our research papers immediately shape public policy, which is both unrealistic, and for many academics, not necessarily desirable. And often there are misconceptions about the timelines of university research and conversations. A lot of what we do takes time, but that is also our comparative advantage. We are never going to have 70 commentators ready to comment on, say, the Indo-Pak conflict today. Instead, it'll be to make progress on long, thorny questions that may take years and years to collect data and analyze.

But equally, there are also misconceptions about donors among academics—and often a condescension or unwillingness to engage with these communities. The misconception among people in academic communities about places like CASI is twofold. One is that very few academics, even faculty, are aware that the nitty-gritty of running a center, including fundraising, is a huge part of these spaces. They aren't just spigots that have easy access to resources for activities. Academics are used to engaging with centers just as places that can provide support or resources. But I've been surprised by how poor an understanding most academics have of the supply side of what makes centers run. We're used to departments that don't have to necessarily engage in those activities in their own ways.

Somewhat irritating to me is that many academics express condescension or unwillingness to engage with donor communities, even as they are eager to request financial support. I am often told by faculty that they don’t want to have to explain their work to non-academics, and especially potential donors. But, leaving aside larger debates on philanthropy as a model, if you want to run a center in these spaces, you have to be willing to do that translation work of explaining our mission to folks who work in very different institutional settings. We shouldn't expect people who are not involved in university life or our institutional spaces to fully understand what they do and why. For example, most donors may not understand the value of a postdoctoral fellowship. It's not a role whose value is intuitively obvious to somebody outside academia. But once you do explain it well, many donors are receptive, which is how we were able to build our program.

Another misconception among academics is what it takes to host academic programs. I understand it, but we receive many requests from people saying, "We want to come, we're in the US, or the East Coast, and we'd love to come and give a talk." And I think the misconception is with what constrains us from accepting all such offers. It isn’t our desire, or the quality of the scholar’s work. It is the sheer work involved in ensuring engagement with their visit.

Especially in the US, even at Penn there's not a natural constituency of 100 people who will come to an academic seminar on India. Actually, getting people to engage with scholars' work—and this may be very humbling for scholars to hear, but I would include myself in this—involves having to really recruit your audience every single time. There is no natural departmental constituency for what centers do. There is no natural undergrad constituency for an academic talk. You could do something in Delhi and have 50 people show up without blinking. That will not be true here. And so, I think there's often disappointment that we cannot have even more and more and more events, and that the limiting factor is just the speaker’s availability or travel costs. It's not. The grinding work is in ensuring a robust turnout for the people we have come to CASI, and ensuring their visit was worth it.

The CASI team enjoying summer in Philadelphia

Rohan: Do you want to tell us what you'll be working on next, what you'll be doing next? You’re not leaving Penn…

Tariq: No, I’m not leaving Penn. I'm just moving up one floor, back into the political science department, and will still remain very connected with CASI, and happily so. I think that next year, I'll be working on a couple of projects. One is looking at policy-making around air pollution and the politics of policy-making on air pollution. Trying to understand why it's not a more electorally salient issue, which, given the level of the public health crisis in India, is an interesting question. The second is a long-standing research project on smalltown governance and on the challenges that small towns in India face. These are towns with less than 100,000 people, which is the vast majority of urban centers in India. But most research on urban policy, which is what I've been working on in the last decade, really focuses on million plus cities. Those are the two big areas that I'm interested in.