The Gap Between Education and India’s Labor Market

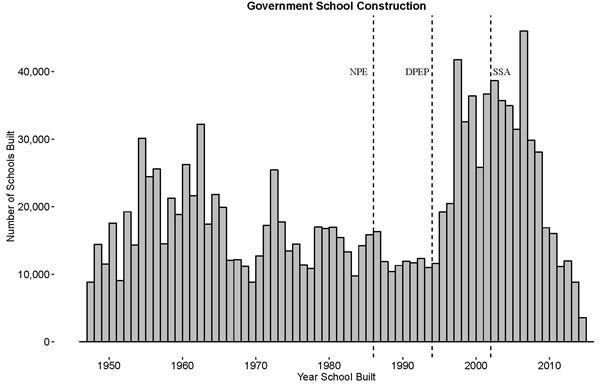

Over the last thirty years, the Indian state has done a remarkable job ensuring its citizens have access to education. Beginning with state-level policies such as the Andhra Pradesh Primary Education Programme and Shiksha Karmi in Rajasthan in 1984 and 1987 respectively, and culminating in the Right to Education Act at the Centre in 2009, the legislative and programmatic attention to education has been tremendous. And with that, there has been a genuine expansion in access and provision at the primary level. In the Figure below, I use historical data from the District Information System on Education (DISE) on the year a school was built to show how the number of government schools across the country has increased relative to three major Central Government education policies, the National Policy on Education in 1986, the District Primary Education Programme in 1994, and the aforementioned Right to Education Act.

Given that it has now been approximately sixteen years since the passage of Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, the first central level effort, what has this flurry of activity brought? Encouragingly, there have been real wins over time. India has nearly universalized access to education and is now educating more people, including girls, for longer than it ever has before. The programs have built schools, gotten children into schools, and had them stay in school for longer. Additionally, it seems like this is also increasing employment and wages. A paper by Gaurav Khanna at the University of California, San Diego, finds that an additional year of schooling has high returns in the labor market, and that large-scale policies to expand education, such as the District Primary Education Programme, redistribute income from high-skilled to low-skilled workers. These are real achievements to celebrate. But this is about where the cheer ends.

On the learning front, the picture is far less rosy. Year after year of results from the Annual State of Education Report (ASER), released by the NGO ASER, has shown that student learning at the primary level is low and not getting better. In 2017, ASER shifted its focus from children at the primary level to ask what is happening with older children between 14-18. Here, the news was no better. Math and reading ability for students in this age group were poor and well below what the government’s own standards suggested they should be. While the government’s own National Achievement Survey is more encouraging, it is not by much. India’s performance in the 2009 Programme for International Student Assessment tests (more commonly known as PISA) was so controversial that India did not reenter PISA again (although India has decided to re-enter for 2021). This story of low learning levels is well known to many.

What should we make of these two contradictory findings? On the one hand, access to education has increased, this is showing real returns on the labor market, and it is redistributing income from high-skilled to low-skilled workers. On the other hand, learning is low for young and older children, is not improving, and is poor even in comparison to other countries. A new concern is beginning to emerge with the growing demographic bulge of large numbers of young adults exiting the school system and entering the workforce. The promises of the education system are failing on more than just quality, and this could have dire consequences for those promised the world.

A new genre of non-fiction has emerged over the last couple of years tracing the gap between the aspirations and realities for India’s youth. Journalists Somini Sengupta and Snigdha Poonam have both written books profiling this new young aspirational class, and many of their dashed aspirations. In both, we find a number of young Indians struggling to find their place in the world. Promised much by their educational attainment, they find their hopes dashed when they emerge into the adult world, with jobs that either fall short of expectations, or a lack of formal employment altogether. Some of those profiled emerge angry, sad, and isolated. So while education has worked to reduce some inequalities, this has still fallen short of promise and the much harder to measure metric of aspirations.

My own work suggests a similar concern—those that have gone to school for longer are less likely to be trusting of a wide number of public institutions in India. Using the Indian Human Development Survey, I find that those children that gained access to education as a result of the DPEP then live in households that are less trusting of public institutions. More concerning, those “DPEP children” are adults today with their political preferences and economic aspirations. Why is this happening? The data suggests that while these individuals are earning more money, they are also doing this in different parts of the labor market: the unorganized and short-term contractual labor. Again, the gap between aspirations and reality has led to resentment.

This traces developments in other regions of the world such as Latin America that has seen the rise of a cohort of youth colloquially called “Los NiNis,” which stands for “Ni Estudian, Ni Trabajan” meaning “They neither study or work.” According to the World Bank, approximately 20 percent of youth in Latin America between the ages of 15-24 are neither in school or working.

So what can India and other countries do? There are two solutions: fix schools or fix the school-to-work transition. While fixing schools is clearly important and there is much to be done here, placing undue faith in schools as the sole panacea for this cohort will likely not solve the larger problem of a large number of youth who enter a labor market not as rewarding as promised and cause further distrust in the education system. Schools cannot be blamed for both their own failings and the failings of the outside world.

That leaves us with fixing the school-to-work transition. And here, most solutions lie with the state. Public sector employment—the much desired sarkari naukri—has not grown apace with the growth in India’s population. According to Devesh Kapur, public sector employment has actually decreased over the last decade. So an expansion of the public sector is clearly in order. While this will not absorb all of those looking for employment, it will help absorb some as well as addressing some of India’s public management issues. Next, some combination of general training, labor market matching, and support for employers in hiring young adults is required. Here, the results for middle and low-income countries are encouraging. Programs that are tailored to beneficiaries, have strong programs for following-up with participants, and include a number of complementary interventions such as both training and employment matching have found long-term success. And to scale this up to a level that will make a dent in India’s school-to-work transition will require some involvement from the Indian state.

It is clear that the question of how to integrate youth into larger society is a universal one that spans more regions than just India. The solution, however, likely does not lie with education. While there are many shortcomings of the education system in India and elsewhere, the question for society is about how to best integrate the young when they have left compulsory schooling but have yet to find work. It is here that further progression through the education system will run head long into frustrated expectations as a result of poor integration into labor markets and larger society. To paraphrase W.E.B. DuBois, the problem of the 21st century is the problem of youth employment.

Emmerich Davies is an Assistant Professor of Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education; a Faculty Associate at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs; and a co-convener of the Brown-Harvard-M.I.T. Joint Seminar on South Asian Politics.

India in Transition (IiT) is published by the Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI) of the University of Pennsylvania. All viewpoints, positions, and conclusions expressed in IiT are solely those of the author(s) and not specifically those of CASI.

© 2018 Center for the Advanced Study of India and the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved.