CASI Deep Dive: Swapna Kona Nayudu on Non-Alignment as Civil Disobedience and Nehru’s Blind Spots

Jawaharlal Nehru still looms large over India. The ideas and ideology of the country’s first prime minister continue to shape debates about its past and future. As a giant of the freedom movement and the leader who steered India through Partition and into its postcolonial life, Nehru left a lasting imprint on the nation’s political institutions and its global outlook. Yet, Swapna Kona Nayudu argues, Nehru remains under-studied, and his thinking is often flattened—both by admirers and critics.

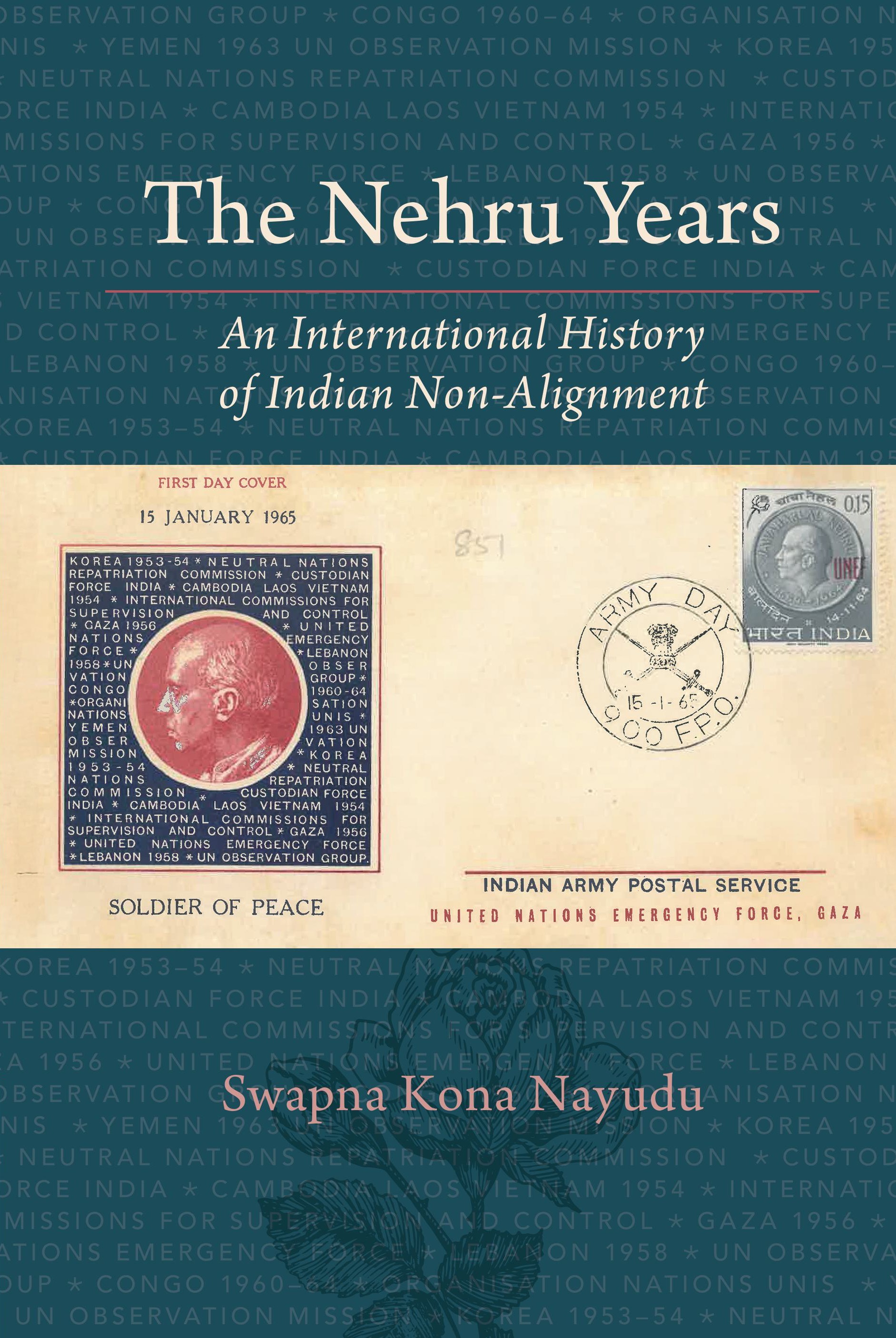

In The Nehru Years: An International History of Indian Non-Alignment (Cambridge University Press, 2025), Nayudu—a Lecturer in Social Sciences (Global Affairs) at Yale-NUS College—revisits one of the central ideas that shaped Nehru’s foreign policy: non-alignment. Commonly seen today as a Cold War-era attempt to avoid being drawn into rival geopolitical blocs, Nayudu shows that non-alignment had far deeper roots in Nehru’s anti-colonial worldview—long before the Cold War had begun.

“Non-alignment is anti-imperial politics that predated and outlived the Cold War,” Nayudu writes. “The early life of the idea was an iterative process, with waves of unmaking and articulating political thought… [which] began in the late nineteenth century and came to a crescendo with the collapse of the Soviet Union.”

The Nehru Years enlarges our understanding of this often-invoked concept by tracing its intellectual lineage—through figures like Mohandas “Mahatma” Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore—and by examining how non-aligned India actually responded to Cold War flashpoints, including the Korean War, the Suez Crisis/Tripartite Aggression, the Soviet invasion of Hungary, and the Congo Crisis.

CASI Managing Editor Rohan Venkat spoke to Nayudu over Zoom and email about her motivations in tackling Nehru and non-alignment, the lack of a “Nehru studies,” the idea of non-alignment as a form of civil disobedience and the former Indian prime minister’s blindness to race.

Rohan: Tell us about your background in academia and how you arrived at this book.

Rohan: Tell us about your background in academia and how you arrived at this book.

Swapna: My first degree was in history, after which I was trained in International Relations with a specialization in security studies. Then I had a few years of working in policy. I was in South Asia for a while—in New Delhi, in Sri Lanka, in Kabul. I then went back to England to do my PhD at King's College London with Sunil Khilnani and Claudia Aradau, King’s College London. I also dabbled in international law, and I think you can see all these interdisciplinary strands come through in the book. Since completing my PhD, I've primarily worked on the Cold War in Asia, particularly India in the Cold War. I also work on the UN, including peacekeeping, and global political thought.

Rohan: That’s a big range of things. Where does it put you in terms of discipline today?

Swapna: I've been very lucky—all the departments I've been at since my doctoral studies, including the Department of War Studies at King's College London, were fundamentally quite interdisciplinary. The reason I went to King's was because I was more interested in focusing on studying war than doing it through a particular discipline. When I arrived at the Department of War Studies, I loved the fact that we had geographers and historians and political scientists and everyone thrown into the mix. My primary PhD supervisor was a trained philologist, for instance. So, we had quite a good mix of people. I would say I mostly do political history. In a sense, my home department is always politics, and I'm always worried about calling myself a historian. But having now produced historical work, hopefully that claim is not too dubious.

Rohan: Tell us the genesis of this project. Where did this book come from?

Swapna: When I arrived at the Department of War Studies, I knew I wanted to work on India, and I wanted to work in the mid-twentieth century period; the founding of the Indian nation, but also the founding of the United Nations. I was quite interested in that crossover, but I didn't know exactly what I wanted to do with it. I was coming from a critical security studies perspective, so the idea really was to go into the archives, find material, and let the research question take shape organically.

That's what eventually happened. I spent a lot of time at both the National Archives of India and the Nehru Memorial Museum & Library, as it used to be called. I concluded that we needed some retelling of the fundamental axis on which India's external affairs was first formed. For instance, in one of my journal articles, I worked on the founding of the Indian Foreign Service. I was quite interested in the question of how a new nation begins to have diplomatic ties or begins to have a diplomatic presence.

A lot of these questions that I had academically became more and more driven as I interviewed erstwhile diplomats. I spent a lot of time interviewing the first few batches of Indian diplomats, like Ambassador Maharaja Krishna Rasgotra and Ambassador Eric Gonsalves. They were all wonderful in illuminating my view of that time. The more time I spent with them, I also realized that a lot of these policies were put together in the spur of the moment, as and when needs arose. And India was very closely examined by other powers as well, both the great powers and other nations that were looking to decolonize or had recently decolonized.

It gave me a sense of that moment being really alive in their minds and helped me animate what seemed really dead and far away in the books. I started thinking about how India chose not to align itself with either of the blocs and how that impacted, so strongly, its position, which is why one of the chapters in the book is called “A Lonely Furrow.” I was quite interested in seeing how Nehru managed to take that position without isolating India. How does someone say no to everything that is current in world politics and then still carve out a position for the nation state, which is so new, so fresh?

Obviously, in many ways, this was happening even before India was independent. So, I had to go back further in time. That's where the book came from. Asking how does one nation have such a meteoric rise in international affairs after being newly independent and refusing to side with anybody? This was quite puzzling. I wanted to look at how it was actually carried out. Someone in a recent review of the book called it very granular. And the reason for that is because I wanted to know how these things actually took place on a daily basis. We understand them as lofty ideas, but how does one actually go about making something like this happen?

Rohan: Forgive me if this is too pithy, but why return to non-alignment? Why return to Nehru?

Swapna: I came to this topic because of my interest in the idea that politics had become subsumed by war, conflict, and ideas of security. When we look at the Cold War, which, from its origins to its consequences, spans nearly the entirety of the twentieth century, we think of conflict as inevitable. Our thinking around this sort of warmaking is also captivated by binaries—capitalism vs. communism, US vs. the Soviet Union, north vs. south. I wanted to look at these questions anew, only to find out through an extensive reading around India’s founding moment, that others before me had also been motivated by this unrest with two-pronged thinking, and had resisted it quite staunchly through thought, word, and action. I wanted to tease out what this resistance looked like and what solidarities it employed.

The scholarship, particularly in International History, that does look at these sorts of questions is also rightly interested in the subaltern narratives of these resistance movements, especially around feminist voices and Afro-Asianist solidarity. I think those are exceedingly important projects. But when it came to the view from India, I thought that the centrist, statist, governmental view had not been studied enough either. So, I decided to excavate what the center was saying.

Rohan: You mentioned getting into the archives and an interest in the period. Did you always know that it would be heavily foregrounding Nehru as a personality? Or is it something that emerged as you started focusing on the material at hand?

Swapna: Not at all, actually. I didn't have Nehru on my mind when I went into the archives. A lot of the focus was actually on Gandhi and Tagore. I was very interested in these two figures. But when I went into the archives, I found that they were completely absent by that point because it was all completely driven by Nehru. And the more I did the interviews with the diplomats, that also really helped me understand his centrality to the project. I started off thinking about Gandhi quite a lot and then moved at some point to realizing that if I wanted to do non-alignment, it would have to be Nehru.

Rohan: For readers who, as you say, might be more familiar with thinking of non-alignment through the lens of Nehru, where do Gandhi and Tagore fit in?

Swapna: Before I answer that, I wanted to say that during the time I was doing my PhD, there was also a sudden surge of writing on Gandhi. There was Faisal Devji's great book, The Impossible Indian. Ram Guha, of course, has his seminal volumes. And there was quite a lot of other writing. Karuna Mantena was doing work on Gandhi as a realist. There was this new way to situate Indian thinkers, not just in global political thought, but also in International Relations. That propelled me to start thinking about figures other than Gandhi who could, perhaps, be situated similarly. And I found that Nehru was quite difficult to place in these categories.

I remember having a conversation with a pretty big intellectual influence on me and saying "Oh, I was interested in Nehru studies," and this person said, "That field doesn't exist, Swapna. It's only Gandhi studies." And I remember thinking, but why doesn't it exist? Because if he's had such a huge impact on India's international affairs, then why don't we have anything that's about him? In terms of the archives, Ram Guha did a talk in London many years ago where he said to students that they should go look at Nehru’s five-volume Letters to Chief Ministers. And I was thinking, there's all this material, including The Selected Works—his own writing; why isn't anyone using that in a comprehensive way? Of course, since I started doing my work, others have also published books using those materials. But this is to say that the interest also came from what was in the materials.

In terms of Tagore and Gandhi, for me, they became really important in the book as sources of thought for Nehru. I kept flitting between reading Nehru as Gandhian and Nehru as Tagorean and trying to figure out which parts he had borrowed from whom. The Gandhi-Nehru relationship is chronicled vastly, and there's a lot of material on that, but not so much on Nehru and Tagore. I was wondering why that was the case and wanted to dig deep. The more I read up on Nehru's travels to China and his view on Asia, the more I could see Tagore peep through. There was a lot of this Tagorean inflection, and it wasn't as Gandhian when it came to international affairs.

I was quite interested in the mixing of methods. There's this Tagorean view of what Asia is like, mixed with a Gandhian method of negotiation and mediation. What was Gandhi if not a great diplomat? A lot of the statecraft is from Gandhi. I was quite interested in how these two sources of thought become a third and completely different approach in the person of Nehru and in his political thought. That's where these two figures come in.

Rohan: You draw on Gandhi’s belief in negotiation—anti-colonial but never anti-British—as something Nehru drew on in his non-alignment thinking. It was even a reason to have discomfort about the NAM…

Swapna: Yes, I think there was a real belief that the door must always be open, and a fear that a new grouping might convey more boorishness than intended. Nehru was quite cautious about India not becoming entwined with others’ issues.

Rohan: To take the other element of the book—non-alignment—you write, “One of the anxieties driving this book was ahistoricism of narratives about non-alignment and attendant inaccuracies.” What do you mean by that? Are the inaccuracies popular or academic?

Swapna: I think there's not enough academic work to make the claim that the academic work is not sophisticated enough. There's been a huge lull between the 1960s and now. After the 1960s, until Srinath Raghavan wrote War and Peace in Modern India, there was almost nothing for a very long time. There might have been some books here and there, but nothing that had a huge impact. Academically, I think a lot of work was done when Nehru was still alive. There are certain inflections and biases there from it being contemporary history.

Today, there is some very interesting work and scholarship that came out over the past decade. But the issue is with writing in the public sphere. I think that there isn't much understanding, but there's also quite a lot of focus on the unraveling of non-alignment. You asked about a popular misconception that I have to keep clearing up. For me, it's the idea that non-alignment failed in 1956 with Hungary, in 1962 with China, or in 1971 with the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union. There's always this anxiety around the failure of non-alignment. Let's chart it. Let's bring it down. Let's talk about when non-alignment ceased to be important or completely failed. And I think that that's actually quite redundant as an approach, and we need to get past it and stop talking about the rise and fall of non-alignment and just talk about what kind of ideas were generated when it was very much alive and active.

Rohan: To lay readers, it might come as a surprise that Nehru and non-alignment are under-covered. Where do you think that comes from? Is it simply a paucity of available work, is it that the academy moved on, is it Western centrism?

Swapna: Three things, I would say here. First is the idea that the Cold War did not “happen” in India. The Cold War is always happening elsewhere, with consequences for India. That idea is being debunked with a huge fresh wave of literature from Cold War history, about the Cold War in Asia in general, and Southeast Asia and South Asia. That is one big change. The second is disciplinary. International Relations as a field is not—and was not for a long time—very popular in India. Whenever it was taught in India, it was taught very much through a Western curriculum. We didn't really think of, for instance, Gandhi as a subject for IR. So, that change is very new and not still fully functional in that sense.

On the history side, however, I draw a lot from the Subaltern Studies Collective. But the collective was pretty much focused on the colonial period or on domestic social-cultural histories of India. The international as a space is not a key subject for them. And so those thinkers, historians, and political scientists who would have perhaps given this period or this subject a fair treatment have not quite been motivated by these questions.

Nehru's international affairs, I would say, is not as extensively studied as his domestic actions. He was in office for 17 years, he was India's first prime minister, he was one of the founding figures, etc. So, of course, there's a lot of work on him and scholarship about him, but I’m not sure how much of that centers on non-alignment, especially after the 1960s.

Rohan: You're making the argument in the book that we need to situate non-alignment outside of the Cold War and also take it away from the non-alignment movement or the idea that India was neutral. Could you tell us a little bit about what you are setting out within the argument of the book?

Swapna: You've touched upon three facets of the book. First and foremost is this idea that non-alignment and neutrality are the same thing. This is actually more prevalent in western scholarship on India. So, to a large extent, that argument is made in the book not for Indian audiences, but for audiences outside India trying to understand Indian politics. A lot of that has to do with the history of the first World War and the ways in which we understand countries like Switzerland and their positioning. Non-aligned states like India, Egypt, Yugoslavia, etc., which are post-second World War, get thrown in with that understanding. A lot of my work in the book is to disrupt that and to separate them from each other and talk about how, for want of a better phrase, this is more of a positive neutrality, where the nation is very active and, just like I had said earlier, it's not isolationist. It's not a position removed from the politics of the day. In fact, non-alignment propels India to be even more politically active.

In terms of going beyond the Cold War, again, I want to rephrase that a little differently because when we say beyond, we often understand that this means non-alignment extends beyond 1991 and the fall of the Soviet Union. What I'm trying to say is that it existed before the Cold War, and it continued to exist after the end of the Cold War because it had already existed before the Cold War. An argument in the book is that non-alignment is not a response to the Cold War, and therefore the end of the Cold War doesn't mean anything to non-alignment as we understand it as political thought. Now, if we take it as a foreign policy approach, of course there are changes once the Soviet Union goes away, because that's a huge change in the way the international system functions. Any nation would have to adapt its foreign policy to that. But I'm also quite interested in its life before the Cold War—Tagore and Gandhi and the political thought behind non-alignment.

The book also talks about how the Cold War is actually a second-order question. The first issue at hand here is non-alignment as a response to questions of peace and empire, which are seen as mutually incompatible. This idea that Western nations would colonize large swaths of Asia and Africa to keep the peace and to help the uncivilized govern themselves is hugely destructive for Indian thinkers. And they're thinking that something has to be done about this. Non-alignment comes out of that very deep anti-colonial sentiment. Because decolonization and the Cold War are overlapping periods, we have some intertwining there that sometimes gets confused with periodization. Those are conceptually two things happening at the same time, but it doesn't mean that non-alignment becomes limited to that period of history.

Rohan: Partly that sense of it being of the Cold War comes with how it has been appraised more recently. But I like the way the book grounds it in the anti-colonial movement, describing non-alignment as coming out of civil disobedience. Tell us a little bit more about its genesis before the Cold War?

Swapna: I can speak to what you said about civil disobedience. Both those words are so striking in their coinage as descriptors of non-alignment. Civil, because active participation in international society is quite important to non-alignment. But also, disobedient because this very international society is in the throes of conflict, and this conflict is playing out on the basis of blocs. And non-alignment is not just a refusal to be in either bloc, but also a denunciation of the blocs, on the whole, as a system. It's quite interesting because they want to actively participate in this society while fundamentally reordering it. And I think that that's so ambitious. That’s actually very exciting to study.

Rohan: In the book, you then set out to see how this played out, in the Korean War, in the Suez Canal Crisis/Tripartite Aggression and the Soviet invasion of Hungary, and then the 1960s conflict in Congo. What drove you to these moments?

Swapna: The subtitle of the PhD thesis on which this book is based was “Critique, discourse and practice of security.” The idea was that there's a critique of security as ordering international politics. Then there's discourse where there's a lot of discussion about what this means, what this will mean for India, what it means under different circumstances. And then there's practice where India basically says, "Okay, we have to use force to keep the peace." We move quite a lot along that arc, and a dismantling, almost, of the original ways in which non-alignment was thought. I was quite interested in picking up case studies that would demonstrate that arc, but also in looking at different parts of the world: Asia, Europe, and Africa. In terms of the diplomatic history, it was quite interesting to see how they were all approached differently.

The book functions on multiple levels. In terms of the actual political thought, I wanted to look at various figures who had informed the ways in which Nehru and the Indian Foreign Service were thinking about these conflicts. In Asia, in the Korean War chapter, you have Tagore. In the chapter on the Suez Canal crisis with Egypt, there's this correspondence from diplomats talking about how Egypt might be in Africa, but it has its face turned to Europe. So, there's this coming to terms with Arab nationalism. And then with the Soviets, it's always interesting, India's interface with Soviet notions of empire or aggression or nationalism. I wanted to pick up a case study that looked at anti-colonial nationalism, but from within the second world. And so, we have that with Hungary. And then the Congo for me was very interesting because it was the first peacekeeping mission where Indian troops had used force. Because I wanted to talk about the practice of security, it all came together in that way.

Rohan: There is one way of looking back at non-alignment and seeing it as purely a rhetorical device, which is heightened by the question of how Nehru handled the Soviet invasion of Hungary (refusing to condemn the USSR even as India clearly took Egypt’s side on the Tripartite Aggression/Suez Canal Crisis). The sense I get from the book is that it was more grounded in the politics of the time, so I wanted to ask how you might respond to a cynical reading of non-alignment.

Swapna: In any work on Nehru and using Nehru's writing, especially because he wrote so much and he spoke so much, the question of rhetoric is always in the room. How much of this is actually intended as political action? A lot of Nehru's writing, I have tried to view not as rhetorical but as pedagogical. He needs to constantly educate his diplomats, the people who work for him, the ministers, etc., because of this idea that India is a very young state and he's running the country. There is a sense that everyone has to be taught how to be political and how to function in this world. Whilst doing that, of course, there is some amount of political-speak which comes into the picture.

More precisely with Hungary, I think that one of the functions of trying to remain non-aligned at that time is also to continuously speak to both blocs. And it's much easier to keep speaking to both blocs when none of them is in the middle of an aggression. That's why if you notice I have the Suez Canal crisis (when Israel, France, and the UK invaded Egypt) and Hungary in the same chapter. Why do we not criticize Nehru for speaking to the British and the French while the Suez Canal crisis is on? When he does that, it’s mediation, but when he speaks to the Soviets, it's pandering. That seems a bit unfair, which is why I put those two together.

Having said that, I do think that this moment represents an unraveling of the idea of non-alignment. Because there is a delay in his responses and there is a reluctance to alienate the Soviets. That does cast somewhat of a shadow on Nehru’s handling of the crisis. The reason the chapter is so detailed is because we're trying to get to the point of understanding what's going on in his mind at this time, and why the ministry of external affairs is doing what it chooses to. From a purely technical point of view, not having had a mission in Budapest really hampers India's response to the crisis. But again, India is only nine years old as a nation state at this point. Naturally, it cannot have diplomatic missions all over the world. So, some of the reasons why that episode turned out the way it did are rather technical.

But in terms of a more macro view of non-alignment and what happened to non-aligned thinking around the time, I do think that it was a moment where there was some unraveling. It's a bit of an inside joke in my mind because when someone picks up the book and it's called The Nehru Years, and it's a history of non-alignment, I don't think people are expecting the book to be critical. And I think that I am interested in it because I view it as, in the end, a failed political project. Even so, there's always something to learn from it. Even if it eventually failed, whenever that might have been, the decline also teaches us so much because even during the decline, it had such a hold on India's external affairs. So, one can only imagine at its peak how powerful an idea it might have been.

Rohan: You write at some point in the book that “Nehru is not a thinker of our century.” Why?

Swapna: Nehru is seen as an institution builder because he built so many institutions, but he's much more than that. Perhaps only second to Gandhi, he really suffers from an oversimplification of his thought. There's a lot of burdening him with ideas or labels that are quite simplified. And a lot of this oversimplification comes from those who look at him with admiration. Those who look at him with adulation end up seeing him as a source of relief in these present political times.

After spending a long time, more than a decade, looking at his writing, I have concluded that he was very good at maneuvering the international space, and he created a space for India to move about in, internationally. And he was an extraordinarily prescient man. He could really see conflict coming from quite the distance. Those are very particular skills that had a very particular function in that historical moment. For instance, he was incredible in the ways in which he supported the UN. At some point, the UN secretary general was writing him private letters asking him to support the UN, because without it, the UN would fall or fail.

What India does today at the UN, we cannot, in a sense, borrow from that historical moment. It would be quite discordant to think about his ideas and transplant them to the UN of today or India's role at the UN today. In that sense, I do think that he was extraordinary for his moment in time. But that moment is now behind us. One of the fears with engaging in this sort of work is to try and transform those ideas into ones of today. And I think that as tempting as it might be, these legacy questions always land us in a soup. And so, I'm quite wary of doing that.

Rohan: Another critique of Nehru comes up in the Congo chapter, on how Nehru and India, at the time, looked at Africa and sought to fit African questions within non-alignment. You describe it as a blindness to race in the handling of both the Congo situation as well as Africa broadly. What do you mean there?

Swapna: The summary argument is that race is a deeply contentious historical issue in African politics already in the 1940s and 1950s. It's already at the crux of decolonization in African politics. And I think there is a parallel and separate Indian experience of that racialized politics both in Africa and outside of it, as we know from, for instance, Gandhi's experiences in South Africa. So, there's a certain multi-layered racialization going on there that Indians experience in a very different way.

Nehru simply viewing all of this through the lens of Afro-Asianist solidarity was just inadequate as an approach. Bringing African nations to the Bandung conference or having solidarities with Nkrumah and Kenyatta and the big leaders of the time was simply not enough to really understand what was happening in Africa. In the Congo, the main pitfall in Nehru's thinking at the time was assuming that because the Congo said that when they become independent, they’d be non-aligned, that Congo's entry into international society would be similar to, say, that of India's or Indonesia's. I think there is blindness there. That ends up going quite wrong.

Rohan: I wanted to engage more with non-alignment as a failed project, and the failure to understand race and assume that African nations will come out of colonialism in the same way. I found that point echoes a reflexive assumption today that India can lead the Global South, just automatically because of its presence outside of the developed world…

Swapna: I disagree because I think these might actually be opposite problems. With Nehru, the difference is that he didn't want to take on this mantle at all beyond what was required to gain India a position at the UN and in international society in general. As I argue in the book, there's a lot of handwringing and reluctance on his part. Even as India keeps increasing its material commitments, at some point it's too deep in the throes of the peacekeeping and cannot pull out.

Nehru is also much older at this point—he dies in 1964 when the Congo crisis is still ongoing. And he just doesn't want to take this on. Personally, he's older, he's struggling with so much at home post the 1962 war with China. So, the last couple of years of his tenure, and indeed of his life, are quite fraught. In that sense, it might be quite opposite to what's going on today, in the sense of India wanting more responsibility and perhaps visibility. By the point we get to Congo, I think that Nehru, and those ambitions, at least on a personal level, are starting to fade. And you can see that with the non-alignment as well.

Rohan: Tell me about Nehru keeping at a distance from even like-minded leaders of the NAM and why you write that “this estrangement did nothing to revitalize non-alignment that would have perhaps benefitted from contestation over its meaning and reflection from a wider variety of sources.”

Swapna: The reluctance didn’t translate into alternative visions of what NAM could look like. India simply receded further and further from solidarist ventures. I don’t expect, anachronistically, for Nehru to have taken that on. We cannot view India’s external affairs in a vacuum—there was always so much going on domestically and the international situation was hugely volatile, so perhaps there was only so much interlocution possible. But yes, the estrangement was not very fruitful for anyone in the end.

Rohan: Did working on this book update your understanding of what happened with non-alignment subsequently, both then in the immediate post-Nehru years and going on to the way we continue to talk about it today?

Swapna: I'm wary of legacy questions. So, I like to think of this as confined to Nehru’s time and then fading out into a completely different foreign policy under Indira Gandhi. I see many more continuities between that latter period and today than I would between the Nehru period and today. But of course, there's a lot to be said for how India still conducts itself in peacekeeping, how India conducts itself at the UN. That is a glorious tradition, and that has continued for decades.

There are parts to this which can be traced back to that period. In terms of understanding what today's politics are based off, I think that it's too much in the past to have that much resonance. What's interesting is that while other nation states are still reckoning with their own histories of participation in these conflicts, these questions come up. So, for instance, a couple of years ago I provided testimony at the Irish Parliament on Ireland's involvement in peacekeeping in the Congo and their interaction with Indian troops in 1964. So, other states are also coming to terms with their own national histories. And some of these questions get thrown up again for discussion when that happens.

In terms of Indian foreign affairs, I think a lot has happened between 1964 and 2025. One doesn't want to make jumps from then to now, but I think under Indira Gandhi, and then again under Rajiv Gandhi, I think there were many changes to non-alignment. Including of course, getting rid of the hyphen. The concept was still very much a matter of discussion until both Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi were in power. After that, we see it less and less as a phrase coming up. And then eventually it gets replaced. I mean, today, there's just a variety of other phrases used. In fact, I think they want to put a distance between non-alignment and themselves.

Rohan: What do you feel people get wrong about this period, about Nehru or about non-alignment all the time? What are the things that you find yourselves having to correct quite frequently, whether it's from the lay world or the academic world?

Swapna: Academically, I think there's way too much discussion on when exactly non-alignment failed and also this idea that some things are obsolete and should stay in the past. If we think that then why are we writing history? This is also a disciplinary dispute. So, you often have this from political scientists who say that it’s long gone and dead and buried. But it's the task of historians to resurrect that which is long gone and dead and buried.

With lay persons, I think the idea that Nehru faltered in 1962 with China overshadows so much of everything else he did, especially in foreign affairs. It's very difficult to get people to move past that and talk about anything else or go before that and talk about everything that happened between 1947 and 1962. So, that's one very big issue that I face. And the other is also just having to answer questions about Edwina Mountbatten. I wish I didn't have to do more of that.

Rohan: What are you working on currently?

Swapna: I'm in the midst of writing my next book, which is a history of India's internationalism in Asia through a study of Tagore's cosmopolitanism in Japan and Bose's militarism in Singapore.

Rohan: Do you have three recommendations for our readers?

Swapna: I am a student of war so Bertolt Brecht’s War Primer, which will probably always be the most lyrical treatment of war; Igort’s The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule is terrifying and, therefore, excellent on war in peacetime; and the documentary Best of Enemies, about the televised debates between Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley Jr.—a real window on what has been happening in the US for the last many decades, and where it all came from.