Sarpanches and Supporters: Everyday Responsiveness in Rural India

In 1992, India conducted the world’s largest experiment in local democracy. The 73rd amendment to the Indian Constitution, passed that year, devolved substantial authority over policy implementation to millions of elected local politicians across rural India. As a result, village politicians gained power over the targeting of benefits from government programs, such as the allocation of jobs in the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee (MGNREGA) scheme. The amendment also brought the government much closer to villagers, giving them direct access to representatives of the state, who now had the power to solve their problems.

A critical question for understanding the consequences of this decentralization effort is one of priorities. Who do elected local leaders—particularly sarpanches, who head the lowest tier of rural government—favor when responding to everyday requests? Specifically, do they set out to represent the often-diverse coalition of voters who elected them, or do they favor narrow groups of voters from their own ethnic group? Similarly, given that surveys show elected village officials are overwhelmingly likely to know their constituents personally—and therefore expected to be aware of the neediest members of the village—do they prioritize the needy over better-off voters?

Caste and Class

To better understand sarpanches’ targeting decisions, I conducted fieldwork in Rajasthan over the past decade—including qualitative interviews with sarpanches, a 2013 survey of voters and sarpanches in 96 gram panchayats, and semi-structured qualitative interviews with 35 sarpanches in 2024. The survey included a unique behavioral measure where sarpanches were asked to allocate five tokens among ten randomly selected constituents to impact a lottery with a prize equivalent to a day’s wage on a government infrastructure project. Those with no tokens received one lottery ticket, while each token distributed by the sarpanch would have given a villager one additional lottery ticket. The requirement to exclude at least half of the ten citizens forced sarpanches to favor some of their constituents over others.

The conventional wisdom on Indian politics suggests politicians are biased to help members of their own caste or jati. However, evidence from our fieldwork does not support this view. We do not find statistically meaningful evidence that sarpanches favor members of their caste or jati over those from other caste groups. This follows from the requirement of local elections in rural Rajasthan, where winning elections requires a plurality of support in typically diverse localities.

Specifically, we did not find that sarpanches favored a supporter from the same caste background when partisanship—meaning affinity for the same political party—and individual support in the election for sarpanch are taken into account. In related research that asked voters about their expectations of receiving anti-poverty benefits or a job in the MGNREGA jobs program, I similarly found that voters were not more likely to expect a benefit from a co-ethnic leader identified as a plausible candidate for sarpanch than a leader from a different jati.

We also considered whether sarpanches favor needy or better-off villagers when it comes to responsiveness. Recent research, which compares the targeting of policy benefits between bureaucrats and elected leaders suggests that sarpanches favor higher status groups—such as higher caste individuals—while work on elite capture also suggests that local governments in poor areas, such as the villages we study, will be more responsive to the affluent than the destitute. To evaluate this question, we measured wealth using an asset index that included seven possessions from a concrete house to a cell phone. We then observed which voters, based on this asset measure, were favored. We found that sarpanches favor relatively poorer supporters, but discriminate against relatively poor constituents that they believe did not vote for them in the past election.

Supporters, Co-Partisans, and Co-ethnics

The basic logic of democratic representation is that elected leaders respond to the voters who elected them—which means that they will be more responsive to supporters who voted for them in the previous local election and to those supporters who support the same political party. In fact, numerous articles on local distribution in India have demonstrated evidence of partisan favoritism in local distribution.

In the context of local politics, sarpanches primarily have authority over the implementation of state or national policies and discretion over which constituents they help in everyday governance. At this level, sarpanches and the voters who elect them tend to be in close proximity to each other, unlike at levels higher up where each representative must consider tens of thousands of constituents. In fact, in a survey of sarpanches about randomly selected voters in their gram panchayat, sarpanches reported to personally know 95 percent of voters. Moreover, political scientist Gabrielle Kruks-Wisner’s research, co-authored with Adam Auerbach, finds that 47 percent of rural voters reported that they would get a response if they approached a local official. This illustrates the proximity between voters and leaders in rural India—and the high level of information available to officials in making decisions about distributing benefits.

Sarpanches are most responsive to those who they believe voted for them in the local election, which is formally non-partisan, as party symbols are not permitted on the ballot in local elections in Rajasthan. Perceived supporters received 94 percent more tokens than non-supporters in the behavioral measure. We also examined biases according to co-partisanship—voters who indicate allegiance or affinity to the same party as the sarpanch, according to a survey question on party attachments.

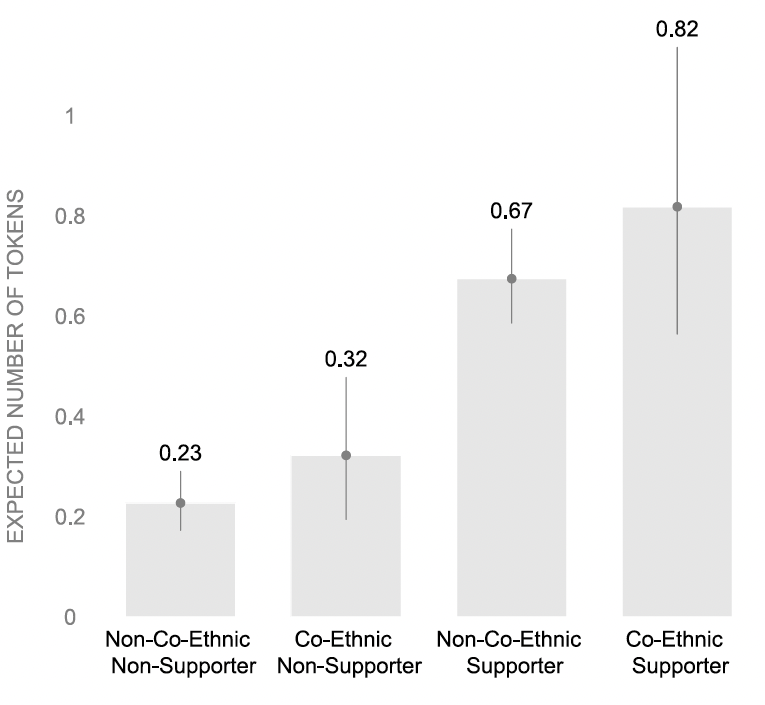

Interestingly, when co-partisans are perceived to be non-supporters, they received .33 tokens on average. This is less than co-partisan supporters, who received .81 tokens on average, but more than .22 for non-supporter, non-co-partisans on average. This means that elected leaders strongly favor those they believe supported them in the elections, particularly when they support the same party, but also show a bias toward those with affinity for the same party, even if they did not receive votes for them in the local election. This perception—that sarpanches favor co-partisans, even when they didn’t receive individual support—also holds up in voter survey experiments, which means that leaders have these biases and voters perceive this as well.

When it comes to ethnicity, the survey suggests that sarpanches are much more likely to distribute a token to a supporter from a different ethnic background, than to allocate the benefit to a co-ethnic who did not support them in the local election.

Figure 1: Token Allocations Across Electoral Support and Co-Ethnicity

As for questions of class and distributing benefits to the needy, supporters one standard deviation below average wealth received 17 percent more tokens than supporters at average wealth. On the other hand, the richest supporters received more tokens than the poorest non-supporters. This means that while there may be some pressure to serve the poor in rural India, sarpanches prioritize the poorest voters when these individuals have voted for them to a far greater extent than when they are not perceived to have supported them politically.

Implications

This research shows that sarpanches are responsive to an inclusive multi-ethnic coalition of supporters without significant ethnic discrimination among them. Moreover, local politicians who play a key role in the implementation of anti-poverty programs and providing everyday assistance favor the poorest constituents—but only when they are also political supporters. This is consistent with a context where voters are understood to select representatives based on who they think will be more likely to help them address needs and demands.

The next question that follows from this research agenda concerns whether the patterns we observed with sarpanches differ from those of local bureaucrats or formula-based methods of targeting that remove elected politicians’ influence over distribution. In ongoing research, I am exploring differences in who local politicians and local bureaucrats prioritize as well as differences in the types of policies preferred by politicians and bureaucrats. If politicians are overall more pro-poor than bureaucrats, despite their political biases, this has implications for the cost of the recent centralization of local governance decision-making, which reduced sarpanches’ discretion over targeting.

Photo credit: Provided by the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee (MGNREGA) scheme