The Anatomy of Public Debt Reductions in India

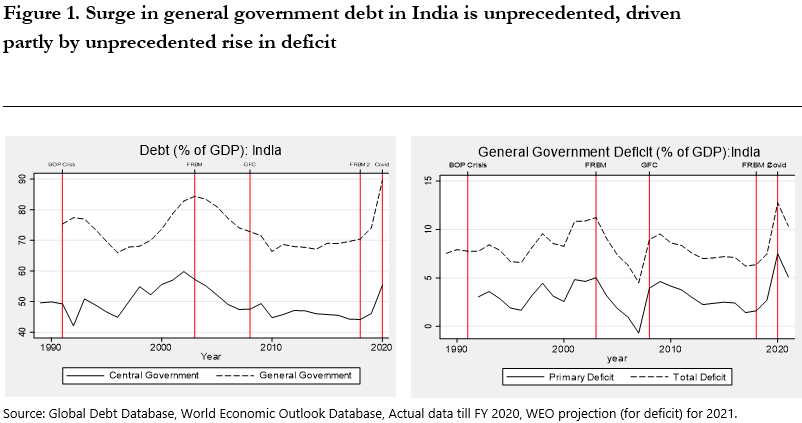

India’s sovereign debt reached unprecedented levels in 2020, partly driven by the policy response to COVID-19, but also by low growth and high interest rates. Some have argued that high levels of debt may be less concerning in an environment of low interest rates. But there is also a significant body of evidence that points to several mechanisms through which high levels of sovereign debt can have negative effects on the economy.

Against this background, we document stylized facts on the recent evolution of sovereign debt and fiscal deficits in India and ask the following questions: What are the costs of high debt levels in India? Are there any silver linings? And what lies ahead? We analyze macroeconomic outcomes during and after debt “surges,” “stabilization,” and “reduction” periods in India and other countries and ask whether past experiences with surges and reductions shed light on different policy options and the tradeoffs for India during the post-pandemic recovery.

The COVID-induced surge in debt in India was unique compared to its own history, but also bigger than that for the average emerging market (EM) economy. The drivers of the debt surge were different too. Both fiscal expansion and the collapse in growth played a proportionately larger role in India compared with the average EM, even as higher inflation played a greater role in reducing debt in India.

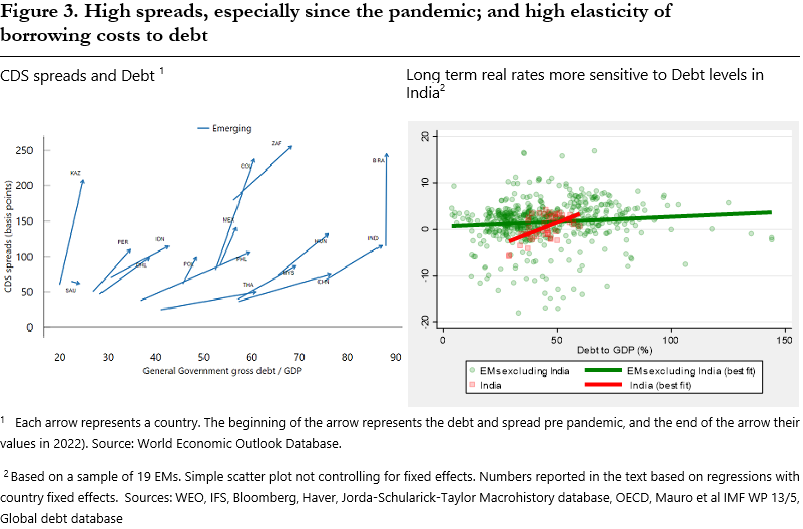

Notwithstanding the high level of sovereign debt, there are a few silver linings for India. The share of sovereign debt held by foreigners—an important predictor of crises in the literature—is low. Moreover, although global waves of debt surges have been followed by restructuring or default, India has not had any such episode so far. Furthermore, long-term real rates remain low in India, comparable to the median EM. That said, we find substantial heterogeneity across countries. While India was closer to the 25th percentile during the last decade, it has now caught up with the median.

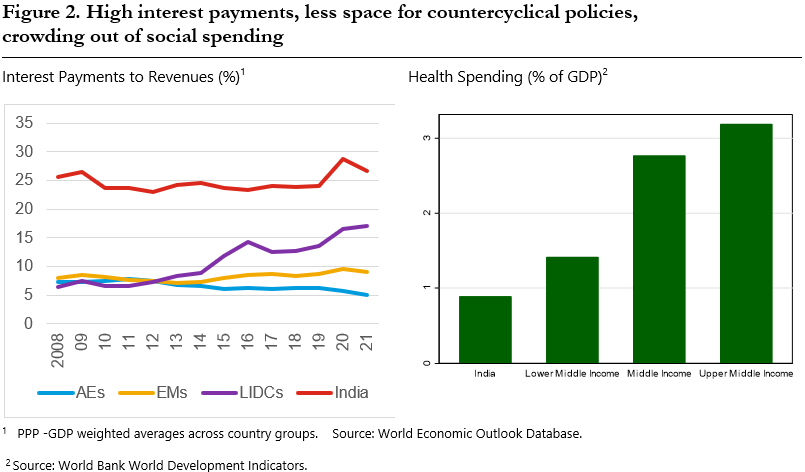

We document substantial costs of high debt. A major one is foregone resources on account of strikingly high interest payments, which at almost 30 percent of overall revenues during COVID, are close to three times higher for India than the typical EM.

High expenditures on interest payments reduce the resources available for countercyclical fiscal policies in the event of negative shocks such as COVID, as well as for social spending in critical areas such as health and education, where India’s public spending remains markedly below peers. Indeed, our analysis suggests that business cycle fluctuations explain a smaller fraction of the variation in debt in India compared with peers, reaffirming the limits to countercyclical fiscal policy on account of high debt levels. Simple calculations suggest that reducing India’s interest payments to revenue to the EM average of 10 percent would release resources of close to INR 6-8 trillion, a figure comparable to India’s pre-COVID general government education expenditure, and about three times its health expenditure.

Another cost of high public debt in India is its impact on borrowing costs. Although real rates in India are low and in line with the median EM, we find that they have increased over time, and that the elasticity of borrowing costs to a unit increase in debt is higher for India than the typical EM.

For example, on average, an increase in debt to GDP by 1 percentage point (pp) increases long-term borrowing costs by 0.19 pp in India, while for a median EM, it increases by only 0.01 pp. Finally, public debt exemplifies an important factor in the assessments of rating agencies too, where India’s debt and deficits stand out as being markedly higher than similarly rated peers.

In order to understand where to go from here, we look at India’s own history and also draw on cross-country experiences. Since 1913, India has had nine episodes of debt surges, five episodes of reduction, and six episodes of debt stabilizations. Surges have typically ended in stabilizations in India, whereas in an average EM, 75 percent of surges end in reductions. In other words, India has been able to sustain debt at high levels without default or restructuring. Across reduction episodes, India reduced debt ratios by 2 pp per year, compared to more than double the figure for the average EM.

We also find that debt surge episodes are associated with worse macroeconomic outcomes—low economic growth and public investment—compared with debt reduction episodes. Moreover, cross-country evidence suggests that the greater the magnitude of the rise in debt, and longer lasting the episode, the greater the associated reduction in growth around the surge.

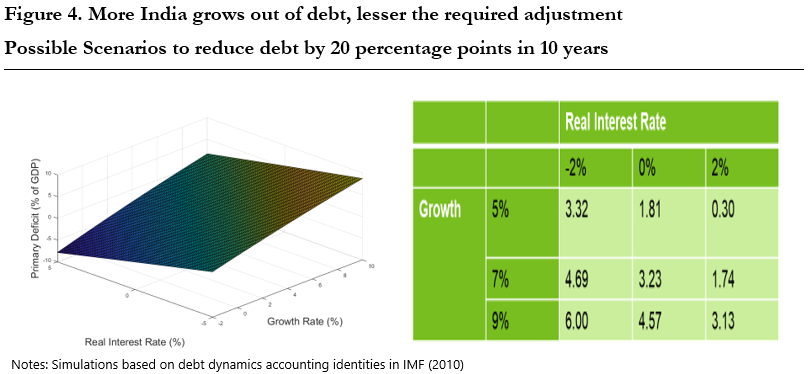

How much debt could India reduce? One way to approach this question is to look at interest payments and additional budgetary resources that could be generated by lower sovereign borrowing. For example, getting interest payments down to 22 percent (still much higher than the EM average of 10 percent) would require reducing the debt ratio to 70 percent, bringing it closer to the median for similarly rated peers.

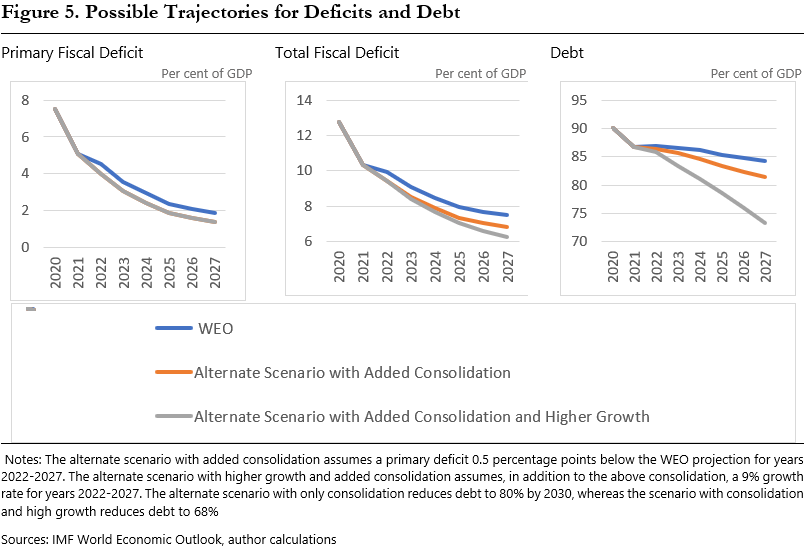

What is a possible path and how long would it take to get there? The higher the growth rate and the lower the borrowing costs, the lower the need for fiscal adjustment. Simulation exercises suggest that if we assume constant values for real GDP growth rate at 7 percent and real rate at 2 percent in line with the IMF World Economic Outlook (WEO) assumptions, a general government primary and fiscal deficit of lower than 1.7 percent and 5.9 percent of GDP, respectively, would be needed every year to reduce debt ratios to 70 percent in the next 10 years (and interest payments to 22 percent of revenues). This would require a sharp adjustment when compared with the FY 2022-23 primary and fiscal deficit at a projection of 4.5 percent and 9.9 percent, respectively, according to the WEO. Importantly, the higher the growth rate and the lower the interest rate, the less the required adjustment. For example, a growth rate of 9 percent or a real rate of 0 percent would open up more space with a primary deficit of more than 3 percent of GDP instead of 1.7 percent, still ensuring the same debt reduction.

While the calculations above assume constant primary and fiscal deficits, allowing for some transitional dynamics and smoothing the adjustment path, we report in Figure 5 illustrative scenarios for debt and fiscal consolidation for India over the next five years. Indeed, evidence across emerging economies suggests that primary balance consolidations outside of recessions could, in fact, be successful in reducing debt, and do not tend to be detrimental to growth as multiplier effects roughly balance the positive impulse from other channels such as higher confidence.

This article is based on a larger project at Systemic Issues Division in the Research Department at the IMF, to understand the evolution of public debt in the post-pandemic world across countries with a team including Sakai Ando, Josef Platzer, Adrian Peralta Alva, and Andrea Presbitero. The authors thank Santiago Acosta-Ormaechea, Elif Ceren, Nada Choueiri, Adrian Peralta-Alva, Dinar Prihardini, Francisco Roch, and Jarkko Turunen for helpful comments, and Swapnil Aggarwal, Chenxu Fu and Manzoor Gill for excellent research support. All errors remaining are our own. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

This article is the first in a series of guest-edited IiT short series. The articles in this series seek to understand India's economic future and its prospects for structural transformation. This article takes stock of the health of India's sovereign debt and gives an overview of the consequences and possibilities in the immediate future. The next three articles will focus on three major national endowments that have been neglected in the course of our development trajectory. The second article will focus on labor force participation of women, the third on water, and the fourth on land. The ability of the sovereign to spend on nation building, along with how we use our endowments, will be key in determining our future.

(Guest Editor: Shoumitro Chatterjee, Assistant Professor of International Economics, SAIS, JHU)