The Numbers Game: An Analysis of the 2014 General Election

In the 2014 General Election post-mortem, much has been made of the fact that the BJP won 282 seats, 52 percent of the contestable seats, on just 31 percent of the vote share. By contrast, in 2009, the Congress got just 206 seats, 38 percent of the contestable seats, on 29 percent of the vote share. What explains this great disparity in the number of seats won given similar vote shares?

At the outset it should be clear that in a multi-party first past the post system discrepancies between vote shares and seat shares are the norm, not the exception. In the last UP Assembly election, the SP won 224 seats with 29.15 percent of the vote while the BSP won just 80 seats with 25.91 percent of the vote. A closer look at the election numbers not only explains the BJP’s ability to convert vote percentage into winning seats, it also sheds light on attitudes in the Indian electorate.

Where did the BJP win its seats?

This analysis uses two concepts that are helpful in examining electoral outcomes: strike rate and competitive party. The strike rate of a party refers to the proportion of constituencies the party wins for a given set of constituencies, and a party is deemed to be competitive in a constituency if it is one of the top two vote getters in that constituency.

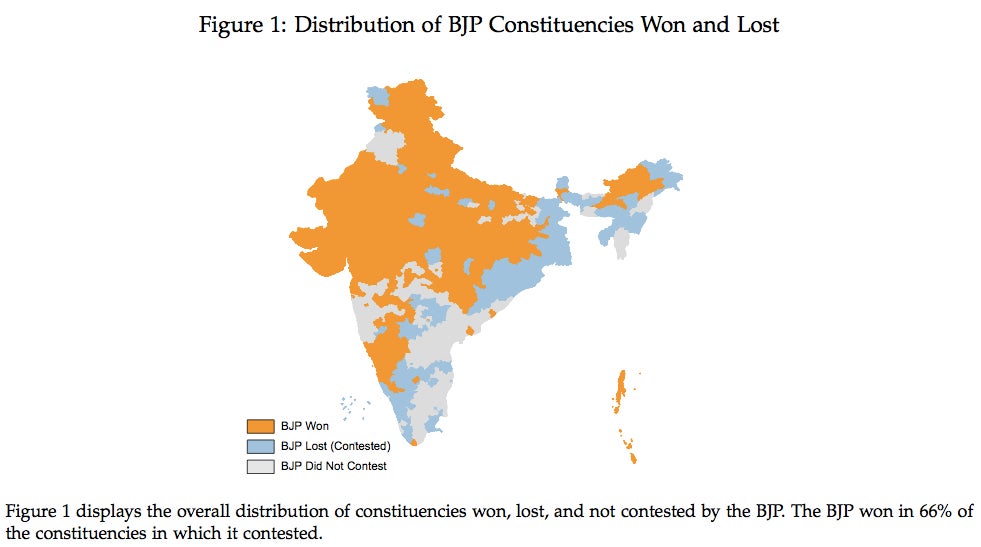

The BJP contested a total of 428 constituencies, winning in 282 and accounting for a 66 percent strike rate. However, there is considerable variation in the strike rate by region and by party opponent.

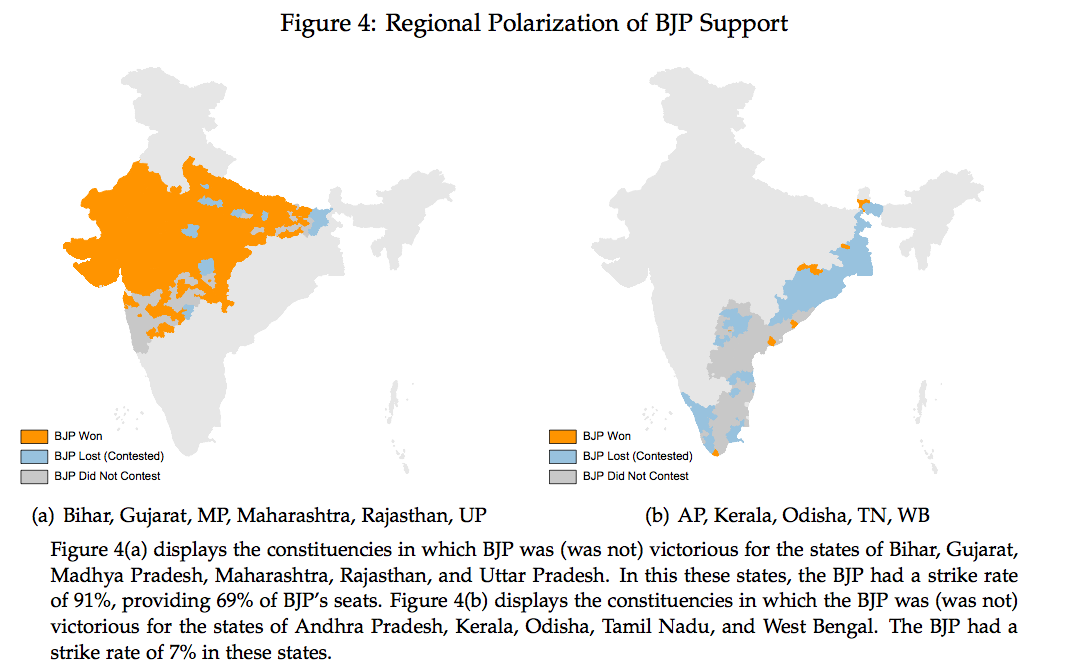

The BJP’s seats are extremely regionally concentrated. Six states alone – Bihar, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh – contributed 194 seats to BJP’s kitty, 69 percent of the total number of seats won by the BJP. In these states, the BJP’s strike rate was an incredible 91 percent among seats that it contested (it did not contest every seat in Bihar or Maharashtra due to pre-poll alliances), but these contested seats comprise only 39 percent of the contestable seats in the general election.

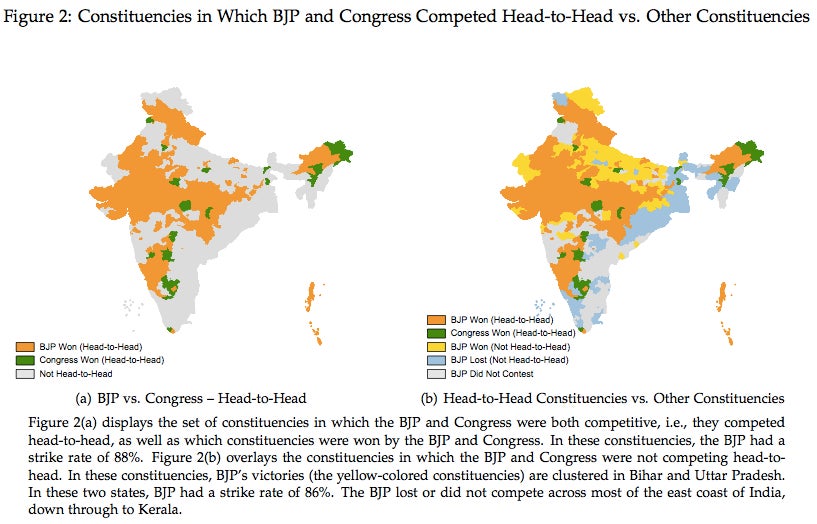

The BJP was particularly successful in head-to-head battles with the Congress. Consider the constituencies in which the BJP and Congress were the top two vote getters; there were 189 such constituencies, and the BJP won 166 of them for a whopping strike rate of 88 percent. By contrast, the BJP’s strike rate was even (49 percent) in the remainder of the constituencies it contested. All told, the BJP and Congress were in a head-to-head battle in 35 percent of contestable constituencies, but these constituencies yielded 59 percent of the total number of seats won by the BJP.

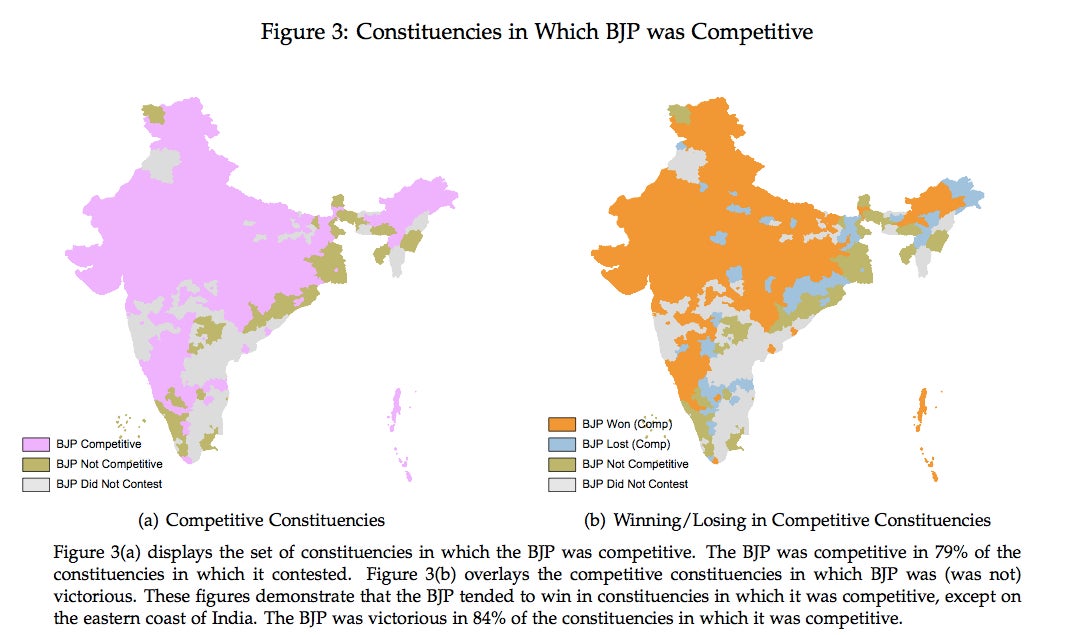

Outside of head-to-head battles with Congress, and outside of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (where the strike rate was 85 percent), the BJP contested 144 constituencies, but was competitive in only 56 of them. Even when it was competitive, the BJP had a lower strike rate of 63 percent. In short, the numbers demonstrate that the success of the BJP in this election was due to its spectacular strike rate against Congress and its remarkable performance in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. These two categories account for 247 of the 282 BJP seats won in this election.

How does this help explain the BJP’s ability to convert vote share into seats? The answer lies in the strike rates in the analysis above. When the BJP was contesting head-to-head against the Congress, or when it was in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, its strike rate was extremely high. Outside of this, however, the BJP wasn’t particularly competitive. In other words, there were very few BJP “wasted votes.” When people cast their ballots for the BJP, it was very likely to be in constituencies in which the BJP won.

Where is the BJP not winning its seats?

For as well as the BJP did in these elections, it still had a hard time breaking into states with strong regional parties and regional identities. This may seem like an odd statement given that the BJP did so well in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, but many people discount the fact that the BJP already had strong bases in those states. The BJP had been a part of the ruling coalition at the state level in Bihar until June 2013 and it was the largest party in the 1999 Uttar Pradesh Lok Sabha elections (and has had double digit seat share since). In this sense, it was not “breaking into” these states.

To understand this point, consider the state of West Bengal, a state where the BJP received its highest ever vote share at 17 percent. The BJP contested all 42 constituencies and won just 2 seats (one of which it had also won in 2009). It was competitive in just 3 other constituencies. Not only did the BJP fail to convert its vote share into seats, it wasn’t even close. Nonetheless, given the weakening of CPM in West Bengal, the BJP may emerge as the main opposition to the ruling TMC in the future. Similar patterns were seen in many states with strong regional identities. The BJP won just 3 of the 12 seats it contested in Andhra Pradesh, 1 of the 8 seats it contested in Tamil Nadu, 1 of the 21 seats it contested in Odisha, and none of the 18 seats it contested in Kerala. These five major states yielded a strike rate of just 7 percent for the BJP.

Interpreting the data

In pre-election analysis conducted by the Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI), using surveys from the Lok Foundation, we argued that the major concerns in the electorate – economic growth, corruption, and inflation – centered around the larger macro-economy. These concerns, packaged with the charisma of Narendra Modi, generated a cogent, powerful national campaign. Congress, on the other hand, found itself in no man’s land, unable to find a solid national identity and too enfeebled in the parts of India with strong regional identities to mount much of a challenge. Congress’ attempt to paint itself as the party of welfare benefits never really took off; voters understood that most welfare programs also require coordination of bureaucrats and state-level implementation, and myriad corruption scandals served to chip away at the credibility of Congress in delivering those benefits.

Those constituencies in which BJP went to head-to-head against Congress served as a referendum on the parties’ respective national visions. The spectacular strike rate of the BJP in these constituencies suggests that Congress never really developed one.

It will be interesting to speculate where the parties go from here. As the data suggests, it will be difficult for the BJP to seriously break into states with strong regional identities. Will it devote significant resources toward this effort or instead, consolidate its power in the places it has already swept? The Congress party, for its part, needs to completely reinvent itself, address its leadership dilemma, and develop a more compelling national vision.

The BJP emerged as the only party with a persuasive national vision in this election, but, as its vote share reveals, this does not mean it is representative of all of India. Apart from the apprehensions of India’s Muslim community, the data shows that significant swaths of India were relatively unaffected by the “Modi Wave.” One of the new government’s challenges will be to address the obstacles generated by this regional polarization. Much will depend on the personal equations that the Prime Minister establishes with the regional leaderships. This will likely be relatively easier with Tamil Nadu, somewhat less with Odisha, and perhaps most difficult with West Bengal.

Neelanjan Sircar is a CASI Visiting Dissertation Research Fellow and a Doctoral Candidate in the Department of Political Science at Columbia University.

India in Transition (IiT) is published by the Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI) of the University of Pennsylvania and partially funded by the Nand and Jeet Khemka Foundation. All viewpoints, positions, and conclusions expressed in IiT are solely those of the author(s) and not specifically those of CASI and the Khemka Foundation. IiT articles are re-published in the op-ed pages of The Hindu: Business Line. This article can be read here.

© 2014 Center for the Advanced Study of India and the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved.