The Backlash Against Internal Migration

In the West, Brexit and the rise of rightwing populists such as Donald Trump in the United States and Viktor Orban in Hungary have been blamed on globalization. In particular, many have argued that unchecked international migration—a prominent form of globalization—has generated a “nativist” backlash. The developing world has long been accustomed to such a backlash. However, the focus of nativist ire in developing countries is frequently domestic rather than international migration. In India, prominent examples of such backlash include the nativist or “sons of the soil” politics of Mumbai and Assam.

In our new book, Nativism and Economic Integration across the Developing World, we document the extent of the backlash against domestic migrants across the developing world. Across the developing world, economic growth and integration have been accompanied by a surge in internal or domestic migration. This migration brings human resources where they are valued the most. At the same time, migration and natural population growth increase economic competition and stretch the resources of the places where migrants end up. As in Mumbai, “original” residents have frequently resisted such developments. Migration is especially likely to lead to nativist politics in places where elections are held at local levels, giving politicians reason to define and privilege “locals” against outsiders. Political decentralization pushed by international institutions such as the World Bank creates new tiers of subnational governance that can be easily captured by nativists.

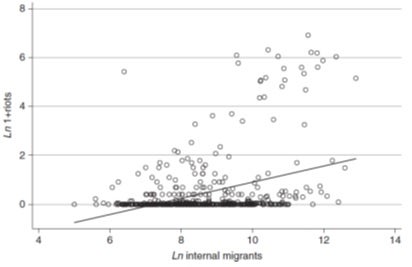

Until recently, scholars lacked systematic data on domestic migration. Through painstaking work, a team of scholars in Australia have put together “migration matrices” for 21 developing countries. We draw on these data to examine the association between internal migration and nativism in various forms. As we show in our book, domestic migration was associated with the rise of “indigenous parties” in Latin America, which have catered to the demands of indigenous communities, particularly over land. Figure 1 shows the strong positive relationship between internal migration and domestic riots across 526 regions in 21 countries. If we look at the data for individual countries, internal migration and riots are positively correlated in 18 of 21 countries. (Two of the remaining countries didn’t have riots. In Senegal, the association between migration and riots is weakly negative.)

Figure 1. Scatterplot of riots and internal migration in subnational regions of Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, with the line of best fit. Note: Figure reproduced from page 58 of Bhavnani and Lacina (2018). Data are for countries in Asia (Cambodia, India, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam), North Africa (Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia), and Sub-Saharan Africa (Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Rwanda, Senegal, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia). Riot data are from the ACLED database; migration data are from the IMAGE database.

Efforts to examine the effects of migration on nativism have typically faced two related problems. First, many hard-to-measure factors—such as socio-economic opportunities—could explain both nativism and where migrants go. Second, the direction of causality could be reversed: not only can migration spark nativism, but nativism likely affects patterns of migration as well. To address these concerns, we focus on natural disaster-induced migration in India. Flooding and droughts are surprise “pushes” to migration. Compared to planned migration, disaster-induced migration is less correlated with the “pull” factors that are characteristics of migrant receiving regions.

For example, internal migration is frequently associated with the rise of anti-migrant politics, as parties cater to nativist sentiments or as new parties emerge to cater to such sentiments. In Maharashtra, domestic migration fueled the rise of the Shiv Sena, which railed against South Indian migrants until the 1970s, then switched its focus to Muslim migrants in the 1980s and 1990s, and has since targeted North Indians, particularly Biharis. We show that when natural disasters pushed migrants into certain districts of Maharashtra, those districts were more likely to support the Shiv Sena in subsequent elections.

India’s local governments also favor so-called natives, discriminating against domestic migrants. State governments hire few out-of-state migrants. The Indian government implemented large scale decentralization reforms in the early-1990s, creating over 200,000 village, taluk, and district level subnational governments overnight. Since competitive elections are held at every level, politicians face strong electoral incentives to define and cater to their own constituents. State governments hired fewer domestic migrants after the decentralization reforms.

Internal migration is one of the surest paths to economic development. As people move across subnational boundaries, they exercise their rights to freedom of movement, and improve their lot. By impeding migration, nativism is a barrier to realizing the promise of migration. How then can we better realize the promise of migration, while reducing the backlash against it? Central governments can redistribute resources to migrant receiving areas to help them cope with the influx of people, and to migrant sending areas, to reduce migration. Like other scholars, we have found that the Indian central government is more generous with allocations to states that are controlled by the prime minister’s allies. New Delhi is most likely to manage the challenge of internal migration well if the government draws its power from a large coalition of states.

Rikhil R. Bhavnani is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Bethany Lacina is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Rochester. This article is based on their recently published book: Nativism and Economic Integration Across the Developing World: Collision and Accommodation. (Cambridge University Press, 2018, Cambridge Elements: Political Economy series, ed. David Stasavage).

India in Transition (IiT) is published by the Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI) of the University of Pennsylvania. All viewpoints, positions, and conclusions expressed in IiT are solely those of the author(s) and not specifically those of CASI.

© 2019 Center for the Advanced Study of India and the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved.