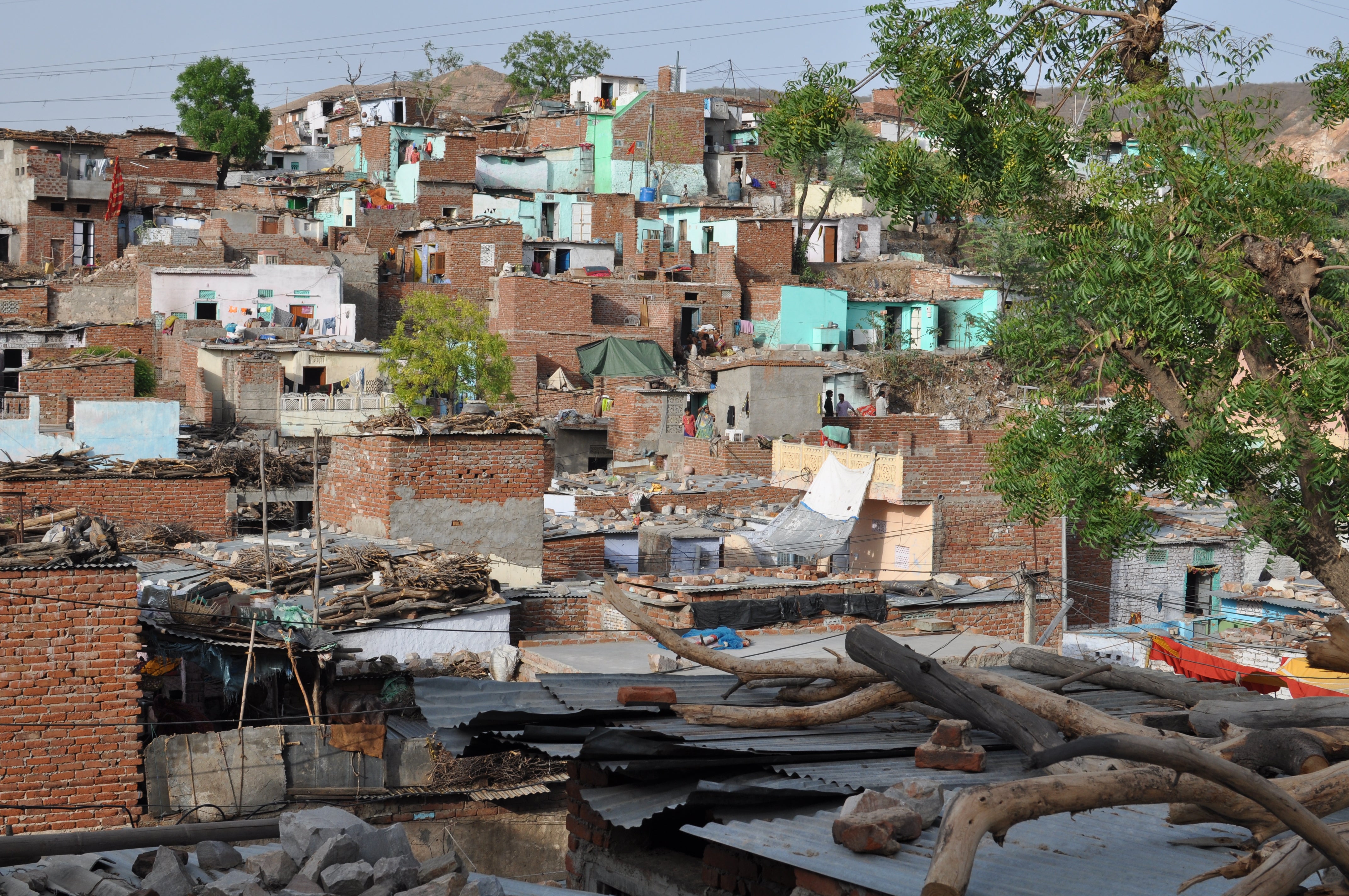

India’s Slum Leaders (Part 2)

In part one of this two-part series on India’s informal slum leaders, we discussed how some slum residents rise to become leaders of their settlement, and the range of activities in which they are involved. In this issue, we draw on our second survey, conducted in the summer of 2016, of a sample of 629 actual slum leaders across those same settlements. Finding slum leaders, let alone a systematic and large sample of them, is extremely challenging, and to our knowledge, has not been previously attempted in India. Indeed, this survey represents one of the few surveys of local political intermediaries in low-income democracies. We draw on this leader survey to outline the social and economic profile of slum leaders in Jaipur and Bhopal, and share what we learned from talking to them about how they build and maintain support within their communities.

Who are India’s Slum Leaders?

India’s slum leaders are predominantly older, relatively well-educated males. 87.76 percent of the slum leaders in our sample were men. Their average age was 47.75 years with a one standard deviation of 11.79 years. The youngest slum leader in our sample was 22 years old; the oldest was 90. The median level of education was 8th grade, which exceeds the average education of ordinary residents by three years. 90 percent of the sampled leaders were literate, compared to 61.85 percent of sampled residents. These results lend support to our experimental findings that residents prefer more educated slum leaders.

Slum leaders engage in a wide variety of occupations. The largest proportion of slum leaders in our sample (26.55 percent) operated small businesses such as general stores, tea and tobacco stalls, motorcycle and bicycle repair shops, and barbershops. Others had small-time government positions (7.15 percent) or vocational jobs (9.54 percent), with the latter category composed of carpenters, tailors, electricians, blacksmiths, and butchers. Slightly less common were private salaried workers (5.41 percent), drivers (5.72 percent), and unskilled laborers (7.31 percent). 4.45 percent were professionals—doctors, lawyers, and engineers—while the rest were artisans, contractors, educators, property dealers, security guards, skilled laborers, and social workers.

How do the occupational profiles of slum leaders differ from those of everyday residents? 45 percent of sampled residents engaged in unskilled labor, transportation jobs, and vocational work. This is roughly twice the percentage of slum leaders who worked in these same occupations. The second most common job was homemaker (25 percent), predominantly held by women in the sample. 11 percent of sampled residents had small businesses of the variety discussed above. Students made up another 5 percent, with the remaining categories all falling below three percent of the sample—security guards, educators, artisans, and professional jobs. India’s slum leaders, therefore, are more likely than everyday residents to be small business owners, government workers, and professionals, and less likely to toil as unskilled laborers in India’s informal economy. These findings square with residents’ preferences for leaders.

India’s slum leaders are remarkably diverse. 160 castes (jati) populate our sample of slum leaders, representing all strata of the Hindu caste hierarchy and a large number of Scheduled Tribes and Muslim zat. 70.75 percent were Hindu, while the remainder were mostly Muslim (26.87 percent), with a small percentage of Sikhs, Christians, and Buddhists (2.39 percent). Most were from Rajasthan (58.19 percent) and Madhya Pradesh (26.71 percent), the two study states. Others migrated from Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Gujarat, Haryana, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh.

The vast majority of slum leaders in our sample had an expressed connection to a party. Of the 544 (86.49 percent) sampled leaders with a party affiliation, 215 supported the INC and 321 supported the BJP. 415 leaders (76.29 percent) were padadhikari, or position holders within a party organization. Given the importance of vertical ties for securing public services, as well as the material rewards associated with brokerage activities, the prevalence of partisan ties among slum leaders is not surprising.

How Slum Leaders Do (and Do Not) Build Coalitions

Our survey data challenges several conventional assumptions regarding Indian politics. First, while leaders openly acknowledge distributing gifts and cash at election time, very few think it does any good. In fact, leaders think that on average only 10 percent of residents have their votes affected by such gifts. Instead, leaders believe the goodwill earned by everyday activities they perform between elections is crucial to their success. Second, leaders do not simply favor members of their own ethnicity. The vast majority of our slums housed residents from dozens of jatis, multiple faiths, states, and linguistic communities. Because of the diversity of settlements, leaders must build multi-caste coalitions of support. We asked leaders to name the ethnicities of the last five residents who sought help from them. 77 percent named residents from multiple jatis. For leaders, focusing on building a client network exclusively of members of their own caste community is simply not a politically effective strategy in India’s diverse slums.

Third, our survey also demonstrates that slum leaders must continuously work to keep resident affections. India’s slum residents are not simply under the thumb of a single slum leader or party boss, and constantly reevaluate their leadership options in densely competitive slums. Like more privileged voters, slum residents frequently switch their support if they feel a different leader or party is more likely to bring benefits to the settlement. 95 percent (2,078 out of 2,199 respondents) of residents stated that they vote in elections. Of those 2,078 respondents, one-third claimed to have voted for different parties across the last several elections. Finally, voting behavior in these spaces often diverges from commonly held assumptions regarding party-voter linkages in India. For instance, of the 542 Muslim respondents in our resident survey, 112 (21 percent) supported the BJP, India’s Hindu nationalist party. And of the 169 Muslim slum leaders in our sample, a similar 27 percent (46 respondents) supported the BJP. 34 of those Muslim BJP supporters had formal positions (pads) within the party. It bears remembering that we cannot claim any of these insights are nationwide patterns, as we have data from only two cities. Still, we believe they offer important, if incomplete insights, regarding the evolving political ecosystems of Indian slums.

Informal Authority and Community-Driven Development in Slums

Understanding the origins, emergence, and activities of India’s slum leaders is crucial for community-driven development programs. Harnessing—or inducing—local participation has become a central hallmark of contemporary international development policies (see Mansuri and Rao 2013). In line with these trends, India’s urban development programs, since the early 2000s, have increasingly emphasized local citizen participation. Rajiv Awas Yojana, for instance, created a handbook for state and local governments on how to form and delegate responsibilities to community-based organizations in slums. Our fieldwork and survey research highlights the bottom up forms of informal leadership and political organization that emerge in slums. These are the actors and networks that development practitioners confront on the ground, and thus require careful consideration in both the design and implementation of community development interventions.

Adam Auerbach is an Assistant Professor at the School of International Service, American University.

Tariq Thachil is an Associate Professor of Political Science, Vanderbilt University.

India in Transition (IiT) is published by the Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI) of the University of Pennsylvania. All viewpoints, positions, and conclusions expressed in IiT are solely those of the author(s) and not specifically those of CASI.

© 2016 Center for the Advanced Study of India and the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved.