The Cold War’s Long Shadow: Indian Foreign Policy and the Current State of Play of Indo-Pacific Geopolitics

(English captions & Hindi subtitles available)

About the Seminar:

China’s rapid rise and power projection in the Indo-Pacific region is dramatically reordering power balances in India’s neighborhood, even as Beijing’s Maritime Silk Road push articulates and implements a comprehensive policy for the region. And while the erstwhile Cold War transformed South Asia, with effects reaching into the present, fresh geopolitical tensions are brewing between today’s superpowers, the United States, and China, with the Indo-Pacific region as its locus. This seminar will analyze strands of continuity and difference between Indian foreign policy in the past and in the present as it struggles to cope with ongoing tectonic shifts in global geopolitics, and examine how it is responding to widening power disparities with China by enhancing partnerships with the balancing "Quad" powers of the United States, Japan, and Australia. It will also make a case for why New Delhi could potentially leverage its position in the current geopolitical conjuncture to enhance its interests and cement its own rise somewhat better than it did during the Cold War.

About the Speaker:

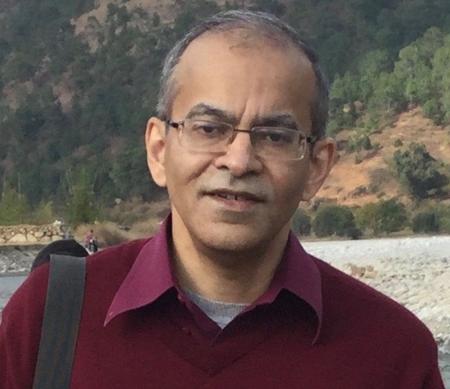

Swagato Ganguly is a CASI Spring 2022 Visiting Fellow and has been Editorial Page Editor of The Times of India from 2009-21. He obtained his Ph.D. in Comparative Literature and Literary Theory from the University of Pennsylvania in 1998, and has worked since then on editorial pages of Indian newspapers, commenting on national politics and international affairs. He is currently Research Affiliate, Lakshmi Mittal South Asia Institute, Harvard University and Consulting Editor of The Times of India. His contemporary research interests lie in strategic affairs, geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific region, Indian foreign policy in a complex, transforming world, and history of liberal thought in India. His two most recent books are: (as author) Idolatry and the Colonial Idea of India: Visions of Horror, Allegories of Enlightenment, Routledge 2018; (as anthology editor) Destined to Fight?: India and Pakistan 1990-2017, Times Group Books 2017. His research at CASI focuses on the geopolitical triangle between India, China, and the United States in the Indo-Pacific region.

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Tariq Thachil:

Hello, and welcome everyone to CASI, the Center for the Advanced Study of India, here at the University of Pennsylvania. My name is Tariq Thachil and I'm the Director of CASI. And I'm delighted to welcome you all to our final talk of the academic year. And we're delighted to be able to welcome as our final speaker, Dr. Swagato Ganguly, who is CASI's spring 2022 visiting fellow a trip long in the making and disrupted multiple times by COVID. So we're delighted that we've been able to host him here in Philadelphia and have him in our office. And now host him for the talk.

Dr. Ganguly was the editorial page editor of the Times of India from 2009 to '21, and has both an impressively eclectic set of scholarly interests and a long connection to Penn. Indeed, he obtained his PhD in comparative literature and literary theory from Penn in 1998, and many of the interests that he developed there informed his first book Idolatry and the Colonial Idea of India, visions of horror, allegories of enlightenment, which was published by Routledge in 2018 and explores literary and scholarly representations of India from the 18th to the early 20th centuries, with idolatry as a point of entry, and charts the intellectual horizon within which the colonial ideas of India was framed, tracing sources in genealogies, which inform even contemporary descriptions of the subcontinent.

And from that deep interest, he has a whole separate distinct set of interests that developed in the years since his PhD, while working on the editorial pages of Indian newspapers and commenting on national politics and international affairs. And specifically those interests all around strategic affairs, geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific Region, Indian foreign policy, and the history of liberal thought in India.

And in fact, in 2017, he edited an anthology Destined to Fight: India and Pakistan 1990 to 2017, which is published by the Times Group Books. And this book compiled selected pieces on India-Pakistan relations that appeared over a 25-year span in the times of India offering, as notes in his introduction, a moving snapshot of this critical relationship. And his research at CASI is focusing and growing out of these larger interests on the increasingly important geopolitical triangle between India, China, and the United States and the Indo-Pacific Region. In addition to being a CASI visiting fellow, he's also currently a research affiliate at the Lakshmi Mittal South Asia Institute at Harvard University, an adjunct fellow at Gateway House and a consulting editor for the Times of India.

Before I turn it over to Swagato for his talk, let me just remind you of your housekeeping rules. If you have any questions, we'll take them at the end of his remarks, and please send your typed questions to me, Tariq Thachil, directly in the chat box. And I'll keep a list of questions and call on you in turn to unmute yourself and ask Swagato your questions directly. Please try and keep your questions brief and to the point so we can get to as many of them as possible.

If you have any clarifying questions during the talk, please send them to me. And I will pose them to Swagato when there's an appropriate juncture in as presentation. Please refrain from using the chat box to post general comments as that can be distracting to the audience and to our speaker. And please note that making a video recording of this talk without prior permission from our speaker is not permissible. So with that proviso, let me turn it over to Swagato, who will talk for the first half of our hour together, and then we'll open it up to Q and A. Swagato, welcome once again to CASI and looking forward to your talk. Over to you.

Swagato Ganguly:

Thank you, Tariq. It's wonderful to be here at CASI, and good also to be invited to offer this seminar today. In terms of what I plan to do today, I will lay out a big picture of the evolution of Indian foreign policy through various distinct geopolitical phases, leading up to the present moment where I will slot India and Indian foreign policy into a larger global framework, larger global narrative of modern history and lay out some implications thereof by doing a real time analysis of the present as it were it, and foreign policy options in the present in the light of the past.

To schematically divide the period that I'll be looking at, which is the period from Indian independence in 1947, roughly coinciding with when the Cold War also ticked off, to the present moment into three broad geopolitical phases. Let me bring up my screen here at this point.

The first phase was broadly speaking the period of the Cold War right up to the breach in the Berlin Wall, followed by the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. From the Indian perspective, it was the period of decolonization during which a broad range of Haitian and African countries attend independence, including, of course, India itself. This was also the period of consolidation of post-colonial states on the world scene.

The second phase is the era of wide ranging globalization that followed thereafter. After 1991, when the world was no longer divided into Cold War Blocks. From the Indian perspective, it was also the era of economic reform that opened up the Indian economy after 1991.

And the third phase is the current phase of a populous backlash against globalization, combined with rising Chinese and Russian assertion. We have seen stronger territorial claims and rise of so-called “wolf warrior” diplomacy emanating from Beijing, roughly coinciding with when Xi Jinping became president of China. And now we have the Russian invasion of Ukraine. These are developments that mark another turning point for global geopolitics, which are now seeing what is being described as a post- post-Cold War Era. In some ways a reversal of the 1991 moment that Francis Fukuyama had called the end of history.

So geopolitics is back, a version of the Cold War is back, globalizing impulses as seeing a reversal, and this phase poses grave challenges, not just for the rules-based international order, but also in my argument for Indian foreign policy itself, which has barely begun to grapple with the many challenges of this new phase.

The Cold War is often seen in an Atlantis's perspective. That is to say primarily as a contest between the United States and the Soviet Union with Europe as the primary theater. But a corrective perspective is provided by the work of scholars, like Odd Arne Westad, who have written about the global nature Cold War. The Cold War was a world war. And if one sees it in that perspective, it's clear that the Cold War wasn't cold in that sense. It became hot in many places. And South Asia and India were profoundly implicated. Two critical events here, one was Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and a multinational jihad that was mounted from Pakistan, aided by the United States, as well as by China, to counter that invasion. And another critical event was the Sino-American Rapprochement itself. That was brokered by the Pakistanis at a time when Washington and Beijing could not have direct contact with each other.

In fact, it was a Pakistani aircraft that flew US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to Beijing for the initial contact where he met Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai. There's a great deal of daring due and cloak and dagger stuff around that flight, when Kissinger pretended to come down with a case of Delhi belly in Islamabad, Delhites might complain, "Why call it Delhi belly in that case? Why not call it Islamabad belly?" But be that as it may, Kissinger pretended to repair to a hill station in Pakistan called Nathiagali. Instead, he slipped out in disguise and bolted this flight to Beijing, where he had the sort of initial confabulations with premier Zhou Enlai. That was to pave the way for the historic meeting between president Richard Nixon and Chairman Mao Zedong in Beijing, in 1972.

Many have seen in that meeting a brilliant strategic move by the Nixon-Kissinger duo that helped win the Cold War for the West. Although a fellow scribe of mine, Pranab Dhal Samanta, writes in the Economic Times in India has a somewhat more sardonic take on this. In his view, as he puts it, "the Americans fought the Soviets during the Cold War and the Chinese won." Recently Mike Pompeo, who was Secretary of State during the Trump administration, said something that was not too dissimilar, when he delivered a speech called Communist China and the Free World's Future. Ironically, those remarks were delivered at Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, where he said, I'm quoting from speech here to give a flavor of his speech. Quote, "We must admit a hard truth that should guide us in the years and decades to come, that if we want to have a free 21st century and not the Chinese century of which Xi Jinping dreams, the old paradigm of blind engagement with China simply won't get it done," unquote.

The Russianist Stephen Kotkin has argued that the end of the Cold War was a mirage because Russia did not change fundamentally. And one could argue that it is a version of Euro-centrism to privilege what happened in Berlin in 1989, over equally momentous events in Beijing in 1989. I'm referring, of course, to the breach in the Berlin Wall and the Tienanmen Square Massacre in Beijing, which were pivotal historical events happening near simultaneously.

Around the same time that Nixon and Kissinger reached out to Mao, the US-India relationship achieved, perhaps, its lowest ever during the Bangladesh War of 1971 when India and the United States were arranged in opposite sides. In fact, one could argue that there were great similarities to the current situation in the Ukraine, but with the roles reversed with tens of millions of refugees streaming into India because of the actions of the Pakistan Army in Bangladesh or what was then east Pakistan. But the Nixon administration turned a blind eye because of Pakistan's role in facilitating the contact with China. While in the present Ukrainian situation, India has been abstaining on UN votes on Russian behavior for reasons of its own. When Western countries, as well as some segments of public opinion in India, have been urging deli to take up a more active stance against Russian actions than it is currently.

Likewise, it's worth noting that many segments of public opinion in Western countries were far more sympathetic to the plight to the Bangladeshis than Western administrations were in 1971. But the Indian intelligentsia share and strategic community has retained a traumatic memory of events in 1971, when a US seventh fleet task force led by nuclear pod and nuclear armed aircraft carrier, USS Enterprise steamed up the Bay of Bengal as the Bangladesh War was on. Even as the Nixon administration urged the Chinese to send troops to India's borders, all of which can be seen as attempts to intimidate the Indians and the Bangladeshis. Although there is a counter example to that example as well, which is less familiar in India today, but in my opinion also ought to be remembered. And I'll counter that counter example in the course of this seminar.

On India, China relations during the Cold War and the phase of decolonization, Indian nationalism tended to view the West as belonging to the colonizing camp against which it had struggled. And the answer from many nationalists, including first Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru lay in a kind of Pan-Asianism or idea of an Asian Federation, where India and China would be the two principle polls. Perhaps, like the European union today, where France and Germany are the two principle polls Nehru had this idea before Independence as well, when China was fighting a Japanese invasion.

And it's worth stating that the sympathies of the Indian Nationalist Movement at that time were overwhelmingly in favor of China and against Japan when Japan invaded China. For Gandhi, for instance, India's freedom could not be obtained without China's freedom. Thus was born idea of Hindi Chini Bhai Bhai or fraternity between India and China.

The history of India China relations we learned in school in India, for instance, at the time, when we were studying history was romantic tale of two ancient civilizations, India and China coming into contact and engaging in rich and peaceful cultural interchange with Chinese pilgrims coming to India, picking up Buddhist ideas, taking them back to China, and so on. This may have happened at the margins, but in truth, there was very little contact between ancient India and ancient China, save a few maritime links. And Indian Buddhism was very different from Chinese Buddhism. Those somewhat distorted romantic notions are, in large part, orientalist myths that have been unpacked by China scholars, such as Giri Deshingkar.

But there has been more contact between India and China in modern times, which is what the Chinese remember, and which framed the Chinese nationalist view of India. So India is where opium came from, which is supposed to have corrupted a ruined Chinese society. Also, sick and other Indian troops helped put down the Boxer Rebellion against foreign influences in China. Indian troops also helped guard foreign settlements in China, British settlements in China. So Indians could be seen as Joe Go, or running dogs of the British. Now this is something that people, like Nehru, found it very hard to wrap their minds around because from their perspective, India had struggled so hard to free itself from the British as it were. And this may have led Nehru and his colleagues to seriously misunderstand how the Chinese viewed India.

Those clashing perceptions or misperceptions were to come to head in the boundary dispute between Indian and China and the 1962 War that followed that India lost and China won. But one can see signs of the clash of perceptions even before. For instance, at the pivotal conference of Asian and African nations held in Bandung Indonesia in 1955, where Nehru made a point of inviting to the conference, as well as of closely supporting premier Zhou Enlai, who was a very skilled diplomat.

You can see a photo in that slide of Nehru and Zhou at Bandung, enjoying a moment of camaraderie and Carlos Romulo, who was the Filipino delegate to the conference, noted how Nehru played the role of mother hen to Zhou throughout the conference, chaperoning him around, introducing him to the other delegates. For context, please remember that PRC government was a pariah government at that time. It had overthrown the Kuomintang, which was recognized as China's legitimate government at that time by the international community. Many Asian governments had also reason to fear the revolutionary communism that Zhou and Mao and their colleagues were propagating at that time.

Nehru also made an impassioned speech at the conference, spelling out his vision of non-alignment and the need to steer clear of Cold War geopolitics. But that did not have as much resonance as Nehru or the Indians might have hoped because many of the paths at the conference were already aligned to one or another of the Cold War blocks. And we can also note the complication of the contradiction in Nehru's own position because he himself promotes Zhou Enlai, who represents the PRC, which of course is a key member of the Communist Block at the time. So effectively Nehru's, non-alignment proves very fragile and it falls apart with India's humiliating defeat by China during the 1962 war.

Now, if we come to the end of the Cold War, the period 1989 to '91, which sees the dissolution of the Soviet Union, what is India's response at the time? Inder Kumar Guiral, who was foreign minister at the time, later he would become prime minister of India, said about non-alignment at the time, "It is a mantra that we will have to keep repeating, but who are you going to be non-aligned against?"" India also has a serious balance of payments crisis at the time and goes to the IMF for a bailout. One of its consequences is that it launches reforms, which open up its economy. It improves trade and attracts investment from the West improves relations with the United States, as well as with Japan and other east Asian powers that it had previously perceived as being too closely aligned to the United States.

And India does reasonably well in the post 1991 globalized era. For one, it improves its security. It conducts nuclear tests in 1998. And thereafter signs and nuclear deal with the United States in 2005, which brings it out of the new nuclear doghouse. In hindsight, we can recognize the wisdom of the nuclear deal and the Pokhran nuclear tests that preceded it because, if India had joined the nonproliferation treaty and forsworn nuclear weapons, as Ukraine did in 1994, the Budapest Memorandum of 1994, and India, just like Ukraine, is located in a very tough neighborhood. India would've been quite defenseless or relatively defenseless if say the Chinese, or the Chinese and Pakistanis in combination had decided to do to it, what the Russians are doing to the Ukraine now. India also saw rapid economic growth for a fairly sustained period of a time that is unprecedented in its history. It saw a growing middle class, the birth of aspirational India. It also saw notable successes in poverty reduction. So according to UN statistics, if 49.4% of Indians were living below the poverty line in 1994, that dropped exactly half or 24.7% by 2011.

So one could argue that India actually did well out of the Western liberal order that marked the globalized era post 1991. And also overall it is quite comfortable within a rules-based international order, but its foreign policy formulations did not really let go of non-alignment which return under different avatars and guises. So it was argued that non-alignment had become so-called multi alignment in which India retained the flexibility to have good relations with everybody. Some policy intellectuals came up with what they called non-alignment 2.0. All of this can be glossed as India wanting to preserve its independence and freedom of action, and to have more of a say in global affairs.

But at the end of the day, multi-alignment is not a hard strategy, if having a strategy presupposes a certain view of geopolitics as having a certain shape and structure, which lead to the adoption of certain priorities by a nation state. And India doesn't have a clear strategic delineation of priorities in that sense, which tends to leave it in a reactive mode, vis a vis the circumstances of the day, rather than actively shaping them.

Although to put that in perspective, it could be argued. The West doesn't have much of a unified and coherent strategy either to safeguard or uphold the liberal order. If this is meant to be a Western-led liberal order, we haven't seen too many signs of leadership coming from the West. [inaudible 00:24:26] Fukuyama, the tendency was to assume that this was a natural order of things. So not much work needs to be done to safeguard or uphold the liberal order. Very recently, Robert Gates, who was us different secretary and should be in a position to know about these things declared that America had taken a 30-year holiday from history.

And in that regard, let me play this small video clip from an interview of Tony Blair, recorded just a few days ago where he makes some candid admissions. This is courtesy of the Economist Magazine. And Blair is being interviewed here by the editor of the Economist who goes by the wonderful name of Zanny Minton Beddoes. So let me play this clip here.

Tony Blair (audio):

But that goes to the point right around the world. You see this, I mean, my [inaudible 00:25:24] does a lot of work in Africa. You see all over Africa, the influence now of China and now increasingly of Russia. The West is slow. It's bureaucratic. It doesn't work out how to build the right relationships. And yet many of these countries would prefer a relationship with America, with Western countries.

So my point is a very simple one. It's that if the West wants to get back on the front foot, it's got to do a number of things that are really important. And they're all linked together by one concept, which is strategy. You've got to have a strategic long-term view of the West and its place in the world. If you do that, then all the other things can flow from that. You can get back on the front foot again.

Zanny Minton Beddoes (audio):

Let's talk a bit about the longer-term consequences of this. Do you think this is a defining moment for the West and for global geo political balance of power?

Tony Blair (audio):

It is a wakeup call for the West, but it should make us think very carefully about what we need to do for the future. And that's why I say it's about strategy. We need to build our defense capabilities. We need to make sure that we are building our alliances, that the trans-Atlantic alliances got to be revived and made strong. I mean, really strong. We have got to have a coherent policy across the piece so that those people, who are our allies, we are standing with them. We're helping them. But above all else, we should have confidence in our own system. And we have-

Swagato Ganguly:

That lack of a strategy may be coming to a head in the current phase of the last decade or so, which Walter Russell has characterized as the return of geopolitics. With Chinese and Russian assertion challenging the Western-led liberal order, we have seen the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent resurgence of the populous nationalism across the world, the breakdown of multi-lateral institutions that was vividly illustrated, for instance, by the lack of international cooperation in tackling the COVID pandemic.

So there has been no transparent investigation of its origins, which could have helped us in tackling the next pandemic, when it comes. And the pandemic itself has become an arena for the strategic competition between the United States and China. So China is stuck in this so-called zero-COVID strategy and finding it difficult to get out of it because it has to demonstrate the superiority of its system, and it's tackling of COVID over the West or over other societies.

And that is leading to a situation where millions of its own citizens are imprisoned in essentially tiny apartments and global supply chains are getting disrupted with cost to China's economy and the global economy, which is still to be counted. And now we've seen the utter collapse of globalizing impulses as embodied by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Western sanctions that have been slapped on it in response, which have the effect of cutting off the world's 11th largest economy from much of the rest of the global economy.

All of which leaves Indian foreign policy caught a cleft stick in this new era of geopolitics. From the Indian perspective, the moment of truth was the Galwan clashes with Chinese troops in Ladakh in June 2020, where 20 Indian soldiers were killed, as well as an undisclosed number of Chinese troops. There's also been the troop mobilization and continuing face off on the border or the LSC or line of actual control, as it is known. As a result of which there is a lot of military pressure on India along most of its very long land boundaries. That is the segments of the land boundary with the Chinese, as well as with the Pakistanis.

And now of course there is a lot of Western pressure on India to move away from its neutralist stance on Ukraine and take up a more active position, condemning the Russian invasion. The problem for India is that it is very militarily exposed at precisely the time when, according to one estimate, India depends on Russia for up to 85% of its weapons platforms. At the same time, continuing dependence on Russia is a non-starter, given that the crippling economic sanctions Russia faces will not only degrade its economic and technological capabilities, but also make it more dependent on China, which also happens to be India's principle, strategic adversary.

So India's walking a very fine line here. It may have no alternative, but to sort of walk this tightrope in the short term, but whether that's sustainable in the long term is a big question. And if falling off from this tightrope is inevitable at some point, it may be good strategy to ensure that India has some control over the direction in which it falls off, so to speak. And two instances may be opposite here. If there is a growing recognition that China is India's principle strategic adversary, and if India, the events of 1971 are strongly remembered, when the nuclear part aircraft carrier USS Enterprise came steaming up the Bay of Bengal.

What's been forgotten in India is November 1962, when the super carrier USS Kittyhawk was also asked to come up the Bay of Bengal. Kittyhawk was commissioned just the previous year here in Philadelphia, actually, at the Naval Ship Yard of Philadelphia, which was operating at the time 1961. And it was ordered by President Kennedy to come up the Bay of Bengal, but this time in support of India, to deter China. And the United States also quickly sent in emergency arms supplies for Indian forces when they were being swept back from the border by the PLA. The United States also leaned on the Pakistanis not to open a second front India when India Indian forces were in trouble on the Eastern front. And ultimately the PLA turned back, vacated most of the T to occupied on the Eastern front. What's the territory it occupied on the Eastern front of what's the state of Pradesh today, which China still claims as South Tibet.

It may also be worth keeping in mind with Jawaharlal Nehru, who was known as, and correctly known as the architect and chief spokesman of the philosophy of non-alignment, said in December 1962. Quote, "There is no non-alignment when it comes to China," unquote. From the west perspective as well, it should, if we are to stretch the metaphor of India falling off a tightrope, offer a safety net, so to speak, to ensure that India has a soft landing. After all, India has a lot to offer too.

It is the only country in the world whose human resources can match China's. It is committed to a rules-based international order. It has the world's sixth largest economy with room to grow much further. It can help with diversification and building resilient global supply chains. The global supply chains are being disrupted today, and building resilient supply chains are the need of the moment. India can help with that. So it may be worthwhile asking India what it wants, and for India also to be clear in its own mind what it wants. And to be prepared to grant at least some of those things.

So what are some of the things that India could want? One is better trade terms. By way of an analogy during the Cold War, the United States offered very generous trade terms to its Asian allies, such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, which helped them build their economies on terms similar to the Marshall plan that was being extended in Europe at the time. So could one research something similar for India at this point?

And India needs arms to defend itself, arms and defense technology transfers, particularly if it is to be weaned away from dependence on Russia in this respect. So for instance, the United States has just concluded the Aukus with the UK and Australia, where Australia is being provided with the nuclear Marines. Could something similar be thought of for India?

Then there is energy security. If Russian oil is taken of the market, that is going to raise the price of oil, which will prove very expensive for India. But also going beyond oil, could one consider clean technology transfers to India, for instance? Which could not only help India make its own energy transition, but one could research, for example, India becoming a global production base for things, like cheap solar panels, at a level that's competitive with China with Western assistance. Cheap solar panels, or electric cars, perhaps, in which case India could supply both its own needs as well as global needs, as well as waivers from sanctions such as the CAATSA sanctions.

So for instance, at this point, India faces sanctions because of the S400 antiaircraft missiles that it is importing from Russia, but could one envisage a co-development or co co-production arrangement between India and the United States to produce a similar antiaircraft missile, for instance. That could be something to consider.

So to conclude, if China is to be balanced in the Pacific region and elsewhere, and the region protected from the negative effects of China's rapid rise, the only conceivable way maybe for the core powers, that is India, Japan, Australia, and the United States, as well as other like-minded middle powers in the region, getting together and acting in a coordinated way. In particular, I think the situation requires an enhanced partnership between India and the United States. We are undergoing a massive geopolitical churn at present, and I believe new situations require new thinking. So, if there is a worry currently about the reverberations of the Russian invasion of view Ukraine in the Pacific region.

For instance, a parallel is drawn between Ukraine and Taiwan. What if China were to make moves on Taiwan? In that case, the United States would be hard put to defend Taiwan in terms of, if you look at the ratio of population or GDP, the disproportion between China and Taiwan is actually much greater than the disproportion between Russia and the Ukraine. GDP, population, land area, et cetera, and the unit states would be very hard put to defend Taiwan. But if one could envisage India as a second Taiwan, for instance, in which case India can defend itself, if it gets the requisite assistance from the United States.

You could, for instance, conceive India as a second base for production of advanced semiconductor chips, which would be invulnerable to a Chinese takeover in the way that Taiwan's semiconductor chip factories are not at the moment. Perhaps, you could have a sort of trilateral cooperation between India, Taiwan and the United States in this regard. So by way of a concluding thought for this seminar, a modus vivendi between India and the west would shore up the rules-based international order. It could also create favorable conditions for India's rice, just as the Cold War created the right conditions for China's rise.

Tariq Thachil:

Thank you so much, Swagoto, thank you so much for that very broad synoptic talk and covered a lot of ground in a short amount of time. Let's pivot to the Q and A. We already have a couple of questions that have come in. One of them, you began to touch on, but perhaps might expand upon. And that comes from Neeta Mehta. Neeta, do you unmute yourself and ask your question?

Neeta Mehta:

You Dr. Thachil. Thank you, Dr. Ganguly, for this talk. My question is, how do you think Russia's predicted decline due to sanctions will impact its ties with India and its role in the Sino-India dispute? Particularly because there seems to be a distrust barrier between the US and India that is not there between Russia and India.

Swagato Ganguly:

Yes, yes. That is the 64 million dollar question. Russia and India have had a long tradition of cooperation. But what I wanted to present in my talk today was if one looks at the Nixon, Kissinger reaching to China in the 1970s as a rupture, there was a history of us India cooperation before that rupture. And there are also sort of interesting similarities between, if you want to look at it that way, the sort of romance that Nehru and his cohorts had with China before the 1962 war happened. And later the romance that the West has been having with China for a long time, from which currently, it seems to be getting disillusioned.

But be that as it may, the trust factor also has to be balanced with the capability factor. At this point with Ukraine fighting back, and Russia not getting the easy victory that it had sought. A huge question is how Russia will supply its own military forces? What is going to happen to it for, for example, if semiconductor chips for advanced defense equipment, which it imports from the West is stopped. Its defense capabilities are going to degrade hugely, and it is itself facing trouble in the Ukraine. So what position will it be? Even if there are contracted supplies to India, will it be able to fulfill those contracts? That is something for India to think about. And while what might have served in a certain geopolitical era in the 1970s, for instance, in when India and the Soviet Union concluded a peace and friendship treaty, it is a vastly changed circumstance now. And India will have to take into account these new circumstances as well.

Tariq Thachil:

Thank you. The next question we have is from Vivek Bammi. Vivek, go ahead.

Vivek:

Thanks. Sorry. And thanks professor, go for your very informative talk. I just was very interested in your clip from Tony Blair. And I think while he's calling for a Western strategy, or a coherent Western strategy, I just want to take it a step back and to look at what I would call a deep crisis in the Western itself right now. And a lot of it has to come from the history of colonization, as well as what you call the de-globalization that we are seeing. In the last few years, Britain has gone in for Brexit, which I think is a complete self goal. And the US has just had four years of the most horrendous de-globalizing talk from, from Trump who might well come back in 2024. So I see a deep crisis in the west, which will probably impede or hamper its search for a coherent strategy to combat both Russia and China, which do not have that hangover of colonization or of any deep introspection about their own societies.

I mean, America is dealing with slavery with the Black Lives Matter. Britain is dealing with its own ghost from the past. So is all of Europe. So I think the burden of colonization, as well as the de-globalizing tendencies, we see all over Europe, as well as in the US itself, I think they're really going to impede any coherent strategy from the West. So in many ways I think the Chinese might be quite accurate in their reading of world history. Though I hope it's not true that the history comes back in cycles and the 21st century really belongs to China and maybe India. We don't know, but certainly a resurgent China. Going back to its primacy in the 16th and 17th centuries. Yeah. Thanks. I'd like your comment on that

Swagato Ganguly:

Again, that's another 64 million dollar question. That is essentially the juncture where we are right now. The previous question was about the trust factor with the United States. Well, one of the questions there is that the United States could, again, revert to a policy, if India partners with the United States. And the United States, let's say Trump comes back to power and changes US policy wholly vis a vis China, or Russia, then India's left exposed. So I think it can only be a very slow process. It's not like flicking a switch, as it were. And that is a given, in fact, I think, that India cannot change its position swiftly. But I think we need to weigh the implications. I mean, you're right, that it could be the Chinese century, but we need to weigh the implications for us.

If let's say the West-led liberal order goes into decline and a liberal order with China in the lead, and Russia as a junior partner, is the future. Whatever the path of colonialism, et cetera, may have been democracies are transparent, rural space societies, which negotiate differences through negotiation and try to seek consensus and so on. Where as a liberal order with China is a leading light. It is going to operate through hierarchy, there will be no consensus. I mean, would we like to have a world order with opaque and hierarchical societies at the head where the notion of rule of law, and checks and balances of absolute power are pushed aside. And we have instead ruled by law and ruled by whoever is the strongest party.

That is something for us to consider. And if India itself is a leading power or a middle power in the world, I mean, which side? Given that the situation is fraught, and we do not really know which way history will go, which way do we try to tip the scales, as it were? Which way do we tip the balance? I mean, that is I think the historical question for us to consider.

Vivek:

Okay. Can I just throw in another bit there, which is that since we are talking about de-globalization, which you talked about, as a new phase, why can't we not conceive of a world where each country or each region has its own autonomy and autarchy, and we are not talking then about a globalized order at all. I mean, that's a hangover of the United Nations. And we know that its abject failures in most cases of conflict. So why can't we think of a new world order in which we are not talking about this grand clash between democracy and autocracy, but rather countries working out their own futures according to their own history and culture and things.

Swagato Ganguly:

Yeah, the problem with that is that then you deny the benefits of trade, which has led to a lot of prosperity. And this is something foreign minister Jaishankar has also pointed out early this year, when he was in Australian in February that the progress and prosperity for the last eight years has been the result of the fact that trading system that is governed by rules. And that, I think, is because of the West-led liberal order. It is governed by rules and is not politically influenced. So if that goes, then we are effectively returning to a pre-1940s world, which we know how that went.

If the question is then what is the alternative? I think we are probably moving into a world where you create much more with friends, rather than across the board. So it's not so much outsourcing as what is being described, nowadays, as friend sourcing, where supply chains run through countries that, on a very broad level, have some political similarities as well. Maybe that is where we are heading. And that is what India should also.

Vivek:

Just to point out that China is India's major trade partner now. So maybe we can go back to the ages of the silk road, where there were independent countries trading quite happily with each other.

Tariq Thachil:

Swagato, since we're almost at time, let me just ask one final question. You mentioned, and this builds a little bit on this discussion, but you mentioned in your initial typology this third phase is also marked by key features in domestic politics across all of these countries, including these kinds of internal populous developments and often populous developments that are inward looking. I mean, you mentioned Minister Jaishankar's comments on trade, but the government's Atmanibhar policy has also been a bit vexed in its own relationship with trade and how exactly self-reliance is being interpreted. And they're not always consistent themes on that, but there is nervousness outside of India, certainly about what Atmanibhar, and what self-reliance that actually means in terms of trade.

But also I was wondering what your thoughts are more generally about the relationship between these developments in Indian domestic politics, but also the connection between foreign policy and domestic politics in India, historically, including for many of the eras that you were talking about, definitely the first two. The thought was that foreign policy decisions were somewhat insulated from the domestic politics and public opinion. Most Indians when they vote, don't really care about foreign policy, don't care about foreign policy actions, don't know very much about that. So it really was this elite sphere.

But recently, including in the 2019 elections, there was some evidence of maybe change, that foreign policy could be folded into domestic political campaigns. That publics were perhaps a little bit more aware if not always caring about those actions, but that they might even be voting implications for foreign policy postures and being strong quote-unquote "national security" in a way that has traditionally not really mattered very much in Indian elections.

And I was wondering if, A) that's your reading as well. And B) if that has consequences for this current moment where public opinion. And I mean, public opinion data in India is not always the most reliable, but does show a complicated picture. It's not where there were elements of public opinion that you referenced that are urging for stronger actions, but there are also elements of public opinion that are strongly pro, not just Russia, pro Putin. And whether you think that the fears of the tail wagging the dog a little bit now that the connection between domestic politics and foreign policy might be growing tighter under this regime. I'm not sure. I'm not sure what you think about all of that, but I'd be curious for your take.

Swagato Ganguly:

Yeah. Yeah. There are a number of things here. Firstly, there is a conscious foreign policy. Foreign policy is articulated by governments or elites in terms of achieving a country's national objectives. But on the other hand, that is sort of unconscious foreign influences that seep in by osmosis as it were. And in that context, yeah, we may say that the Indian politics operates in its own space and it has nothing to do with what is happening elsewhere in the world.

But to my mind, what happens in the United States is deeply influential across the world. And in that sense, if you have a situation where the president of the United States denies peaceful transfer of power, I mean, that has enormous reverberations. I mean, in that situation, you can almost think of, if authoritarian leaders, like Putin or Xi, thinking, I mean, if this is democracy, then I mean, liberal order is all over by the shouting and it just needs that final shove. [inaudible 00:57:38], if you want to paraphrase what the [inaudible 00:57:41] people who demolished the [inaudible 00:57:43] did, and the [inaudible 00:57:46] came in Ukraine, so to speak.

In that sense, it one should not look at it. And in case I gave the impression that the future world order is certain countries in one camp, other countries in another camp, that's not the way it's going to be because the sort of strong man ethno-nationalist model cuts across, I think, blocks. Whether it's Xi or Putin, or you have the equivalence in the West as well, in India as well. But in terms of constructing a liberal world order, those are some of the internal costs that Western countries, as well as India, will have to deal with as well. Some of the internal demons, it will have to fight. It's not just external, it's not just on the border, facing off with the PLA across the LSC. It's internal as well.

Tariq Thachil:

Yeah. Okay. Thank you. That's perfect. That's right on time. We did have a couple of questions we couldn't get to, but I will save them. And so that I can pass them onto our speaker. And apologies for not being able to get to all of them, but Swagato, thanks again for giving us this thought provoking talk and for closing our academic programming for the year with such a great set of insights. So thank you again for joining us and thank you everyone for joining us as well. Please do subscribe to our newsletter, if you want to stay informed about upcoming events for the academic year, 2022, '23. And I wish you all the best. Thank you for joining us for the year.