Staying with the Struggle: Loving and Laboring in Bombay Cinema

If there is one thing historians can agree was fundamental to shaping the Bombay film industry, it is intense precarity. The commercially powerful and globally-recognized film form that we now call “Bollywood” took its first steps at a time when India was under colonial rule, when no financial institution would touch this uncertain new enterprise, and when very few workers were willing to risk their reputations in a field considered taboo. And yet, in the mid-1930s, Bombay became the site of a dynamic film industry, a cine-ecology with roots spreading in many directions. More than 2,000 “talkie” films were made between 1931 and 1945 and at least 40,000 people were formally employed in the film industry on the eve of the Second World War. This is when a new historical figure entered the picture: the struggler.

The word “struggler” means something so specific in Mumbai that it has become a part of urban patois, part of the hybrid lexicon that is called “Bambaiyya.” To struggle in Bombay is to hustle for that elusive “big break” in the movies. The struggler is a very specific social figure, someone who aspires to make a name in the movie business but who has no insider contacts or social connections. In this context, the struggle is both a response to and symptom of the many precarities that continue to mark media industries today.

Recruit advertisements published in filmindia magazine in December 1945.

In the 1930s, all film roads started to lead to Bombay. Hundreds of film aspirants of all shapes and sizes converged on the city to see if their luck would shine in the world of cinema. This was a very peculiar historical phenomenon—never before had there been a mass industrial form that attracted hundreds of workers in pursuit of something more abstract than money. Cinema’s great promise in this period of acute unemployment was wealth combined with fame and creative fulfillment. Cinema also offered the opportunity to announce oneself as modern, working in a medium that was emblematic of technological modernity and the romantic articulation of individual desire. The struggler, armed with nothing but dreams of greatness, “came from far and near. From the heights of Srinagar. From the heat of Madras, Delhi, Punjab and all the four corners of India” (Zabak, filmindia, September 1940). So remarkable was this influx into Bombay that journalists pathologized it as “movie mania” and parents sent heart-wrenching messages to film magazines begging their children to return home.

A missing advertisement sponsored by distraught parents, June 1939.

In my new book, Bombay Hustle: Making Movies in a Colonial City, I pay close attention to the desires of those film fans who chose to remake themselves as film workers. The fan-as-worker embodies cinema’s drive to socially reproduce its own labor force and offers important insights into the organization and operation of media industries across the world. The early film industry in Bombay was acutely undercapitalized and raising finance for filmmaking was a daily hustle. The struggler’s historical appearance at this moment is enabled by this financial hustle. Many of Bombay’s most famous film producers balanced their financial risks off the contingency of numerous wage workers, stunt artists, light boys, and extras—all forgotten today. The struggler’s dreams of film fame allowed a labor surplus to flood the city, creating a continual turnover of expendable bodies that helped build a beloved and resilient cinema industry.

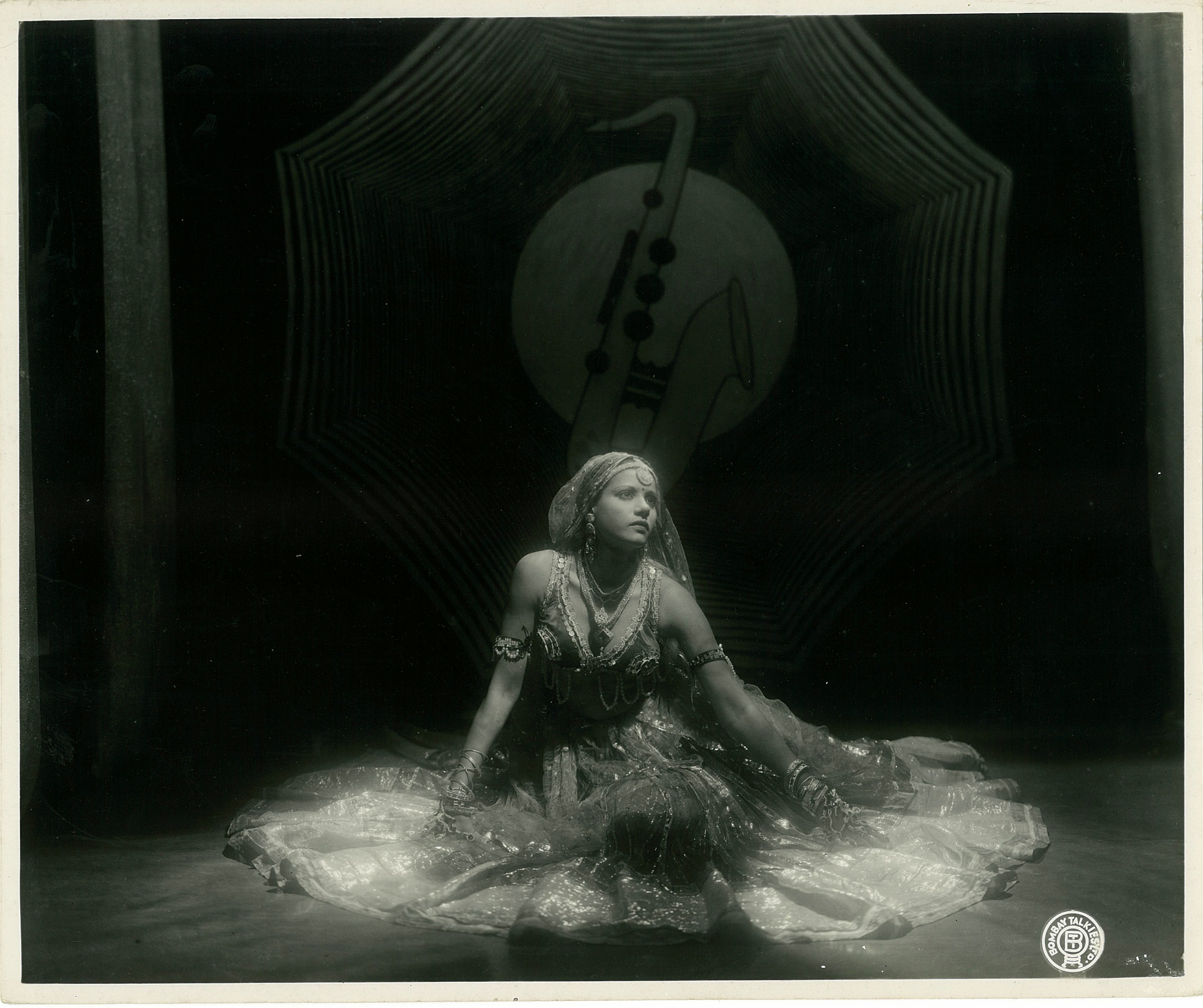

Bombay Hustle book cover featuring a production still from the shooting of Achhut Kanya (1936).

Bollywood is a multi-million dollar industrial assemblage that is popularly viewed as glitzy and glamorous. The news media focuses on stars and other prominent film personalities, and even the negative press that Bollywood attracts is limited to the personal lives of celebrities. By shifting attention to the struggler or film aspirant, we start to see the undocumented forms of love and labor that keep this industry afloat. And I want to stress that we view strugglers not as naïve victims or as heroes but as a complex group with complex desires.

A young man waits in the sun for the next shot, holding a clapper board. Photo taken during the shoot of Izzat (1937). Image courtesy the Josef Wirsching Archive/Alkazi Collection of Photography.

The first thing to understand about struggle is that it is continuous. Even though the dream of stardom is propped up by real stories of success (such as the story of Sulochana, a telephone operator who became a huge star in the 1930s), only a handful of film aspirants actually achieve this level of fame and stardom. Most others remain stuck in a struggle that is continual. Disappointment and rejection are a fact of life and yet, as casting director Nandini Shrikent points out, the struggler still has “to get up in the morning, keep going day after day.” Struggle is therefore marked by a peculiar temporality, one that is decisively oriented toward the future but also determinedly grounded in the present.

Sulochana, nee Ruby Myers, was a beloved star of the silent era and made a successful transition into the talkie period. Many film aspirants of the times mentioned their love for Sulochana as one of their reasons for joining the film industry.

A critical experience of the film struggle is the practice of waiting. The struggler shows us that waiting is not passivity; it is a specific kind of labor. The struggler waits for phone calls to be returned and for agents to bring good news. Meanwhile, she continues with other activities that prepare the ground for the future—taking better portraits for the portfolio, submitting CVs, exercising and training, doing the rounds of studios, and networking. Waiting, therefore, is an engaged mode of being in the world, constantly alert and ready for a different life.

Madam Azurie, one of India’s first film choreographers, was drawn to cinema because of her intense adoration of the star Sulochana. Image courtesy the Josef Wirsching Archive/Alkazi Collection of Photography.

Since waiting and preparing are continual processes, the struggler has a very different relation to late capitalist time as compared to a factory or office worker. There is little separation between work, leisure, and self-care—a phenomenon that is painfully familiar to us today in the new gig economies of global capitalism. On the streets of present-day Mumbai, struggle is a badge of honor, a code word comprehended by a wide community of the new precariat who read it as respect for the daily hustle of surviving in an overpopulated, competitive environment. Today’s cultural worker is interpellated by what Angela McRobbie has termed the “creativity dispositive,” in her book Be Creative: Making a Living in the New Culture Industries (Polity, 2016). The creativity dispositive refers to an ideological apparatus that enables, even validates, precaritization by opposing creativity to aspirations for job security, regulated work hours, or health insurance. So, while freelancing in the gig economy is a necessity for many white-collar workers today, it is misleadingly framed as a choice. Thinking through these ideas in the context of the 1930s film struggler, one recognizes immediately a similar impulse to normalize, even romanticize precarity by framing insecurity as adventure. In this way, the early twentieth century film struggler serves as a historical precursor to the contemporary production of a new precariat, particularly in the so-called creative industries.

Advertisement posted in Mumbai, 2020, inviting “fresher” film aspirants to pursue their passions by applying for jobs as “dancer, singer, spot boy, helper, camera man, AD, production controller, light man.” Photograph by Avijit Mukul Kishore.

Even though today’s Bollywood is internationally celebrated, Mumbai’s cine-ecology continues to be a fraught place, battling multiple contingencies from a pandemic to political scandals. However, just like the city which expands and makes space for people and their dreams against the grim urgency of rising sea levels, Bombay’s cine-workers have stayed with the struggle. The daily struggle of film fans, extras, and workers of all stripes is a determined effort to make meaning of their fragile lives in fragile times. Through their situated and libidinous investment in cinema, strugglers compel us to rethink our own relation with cinema and unsettle overly utopian or deterministically structural readings of Bombay cinema.