Policy Gaps and the Holy Grail of Universal Eye Health

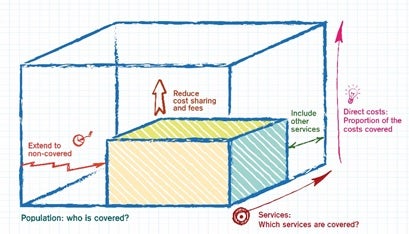

In 2015, member nations of the World Health Organization set about achieving universal health coverage (UHC) as one of their targets when adopting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). UHC is defined by three components: health care access for all individuals and communities, comprehensive care, and financial protection.

Since access is foundational to building comprehensive and affordable health care, primary health care (PHC) is recognized as a key strategy to ensure that everyone in need of care is able to get into the system. Until recently, PHC was confined to maternal, child health, and common illnesses. However, since becoming a signatory to the global initiative to address non-communicable diseases, India has expanded the scope of PHC to include hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes. While new strategies and technologies are being put in place to realize the aspirations of UHC, there is an urgent need for new or changes in policies and regulations to enable such initiatives to become effective. The current, often decades’ old regulations that were relevant then, now have to undergo a paradigm shift, both to accommodate the technological advances and enable the new initiatives.

When it comes to eye care, the strategy for providing screening and some level of primary care at the community level in India (and most developing countries) is essentially limited to periodic community outreach events like eye camps, typically conducted once a year in a given community. A study done in South India in the late 1990s showed that less than 7 percent of those who already felt they needed an eye care intervention attended an eye camp, even when it was in the same or a nearby village. On a population coverage basis, this was under 0.25 percent, while an estimated 20-25 percent of the general population would have some eye care need. In hindsight, it’s clear that an eye camp that happens once a year for five to six hours, is unlikely to cater to the needs of all, reinforcing the need for permanent, year round primary eye care services.

My colleagues and I conducted a case study to demonstrate the feasibility and policy changes that have to be enacted to make this UHC goal an effective reality. As the first step, we broke down primary eye care conditions into case findings, treatments, and follow-ups.

With the advent of technologies like broadband, telemedicine, and low-cost imaging, we chose to set up telemedicine and information technology-enabled primary eye care centers (Vision Centers) with simple user interfaces. The first Vision Center was launched in 2003. Since then, 75 such centers have come up across rural Tamilnadu, covering a population of over six million. The average population coverage is around 25 percent—going as high as 50 percent in older centers (half the population had visited the Vision Center one or more times for some eye condition). About 90 percent of the patients visiting Vision Centers receive complete care—diagnosis, treatment advice, and medicines or prescribed spectacles. While patients pay for these, they are priced affordably and everyone receives them immediately. As necessary, some of the patients are referred to the base hospital for surgery or more advanced care. Patients’ compliance to referrals is very high since referrals are limited to those with advanced conditions requiring surgery or specialized investigations. Here, they have the option of getting the services at the hospital at subsidized rates or for free. This combination of high coverage, addressing all eye conditions, and being affordable meets the three components of UHC.

With the advent of technologies like broadband, telemedicine, and low-cost imaging, we chose to set up telemedicine and information technology-enabled primary eye care centers (Vision Centers) with simple user interfaces. The first Vision Center was launched in 2003. Since then, 75 such centers have come up across rural Tamilnadu, covering a population of over six million. The average population coverage is around 25 percent—going as high as 50 percent in older centers (half the population had visited the Vision Center one or more times for some eye condition). About 90 percent of the patients visiting Vision Centers receive complete care—diagnosis, treatment advice, and medicines or prescribed spectacles. While patients pay for these, they are priced affordably and everyone receives them immediately. As necessary, some of the patients are referred to the base hospital for surgery or more advanced care. Patients’ compliance to referrals is very high since referrals are limited to those with advanced conditions requiring surgery or specialized investigations. Here, they have the option of getting the services at the hospital at subsidized rates or for free. This combination of high coverage, addressing all eye conditions, and being affordable meets the three components of UHC.

This scaled working model of universal eye health has widespread potential and its underlying principles and technologies could be replicated across all disciplines of health care. Within eye care, scaling has happened across the Indian states of Tripura, Chhattisgarh, and Tamilnadu, and quite extensively in Bangladesh. However, several policy gaps are preventing this from being scaled to its full potential. A lot of the policies and regulations were formulated at an era when the current technologies were not present and the services were largely urban-centric. Two major policy areas, in particular, need to be addressed.

Technology & Tele-health

Telemedicine and remote diagnosis have been around for over a decade now and have many applications from radiology interpretation to cardiac consultation based on ECG. The Government of India has, in fact, been promoting telemedicine since 2001 with the Indian Space Research Organization providing connectivity to remote rural areas. On the other hand a lack of policy guidelines gives rise to situations such as the one reported by The New Indian Express in September 2018, in which a doctor couple who provided remote consultation was charged with medical negligence by a Bombay High Court, declaring such consultations as illegal, leading to a negative impact on the teleconsultation industry.

Similarly there are examples of the profession also shunning such advancements, as reported by The News Minute in May 2019, in which Karnataka Medical Council Vice President Dr. Kanchi Prahlad stated, “Online consultation using these apps violates ethical medical practice. These apps are unethical and there is no question about it.”

UHC can become a reality only through a PHC approach. And comprehensive PHC can be successful only through the deployment of digital technologies like tele-health and artificial intelligence. This requires enabling policies.

Drug Supplies

A patient’s health condition doesn’t improve unless the patient is able to get the prescribed medicines and use them as directed. When medications are prescribed for specialty conditions (like ophthalmology) at the village level, such medications are not available in local pharmacies, even if they exist, which often is not the case. The patient then has to go to the nearest town, at considerable expense and effort, to get the medication and in most instances this doesn’t happen. As a result, the patient’s condition doesn’t improve and often deteriorates. The Pharmacy Act stipulates certain minimum physical infrastructure and qualified pharmacists to dispense the medications. This works fine in urban settings where the scale of operations can support such staffing and infrastructure. At the grassroots level, the current regulations will obstruct patients from getting medications in a timely and affordable manner. This necessitates appropriate policy changes (such as innovations like the Nuka System of Care in Alaska).

The current policy and regulatory framework doesn’t work at the primary level, which happens at a much lower scale. Similarly, policies need to be cognizant of technological advances and their demonstrated potential, as well as redefine what staff at the primary level can do with technological support. Such changes will help drive the primary care approach, which is fundamental to achieving universal health care.

Thulasiraj Ravilla is the Executive Director at Aravind Eye Care System (Tamil Nadu) and a CASI Spring 2019 Visiting Fellow.

India in Transition (IiT) is published by the Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI) of the University of Pennsylvania. All viewpoints, positions, and conclusions expressed in IiT are solely those of the author(s) and not specifically those of CASI.

© 2019 Center for the Advanced Study of India and the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved.