From Raj Kapoor to Aamir Khan: Understanding Bollywood Stars as Cultural Diplomats

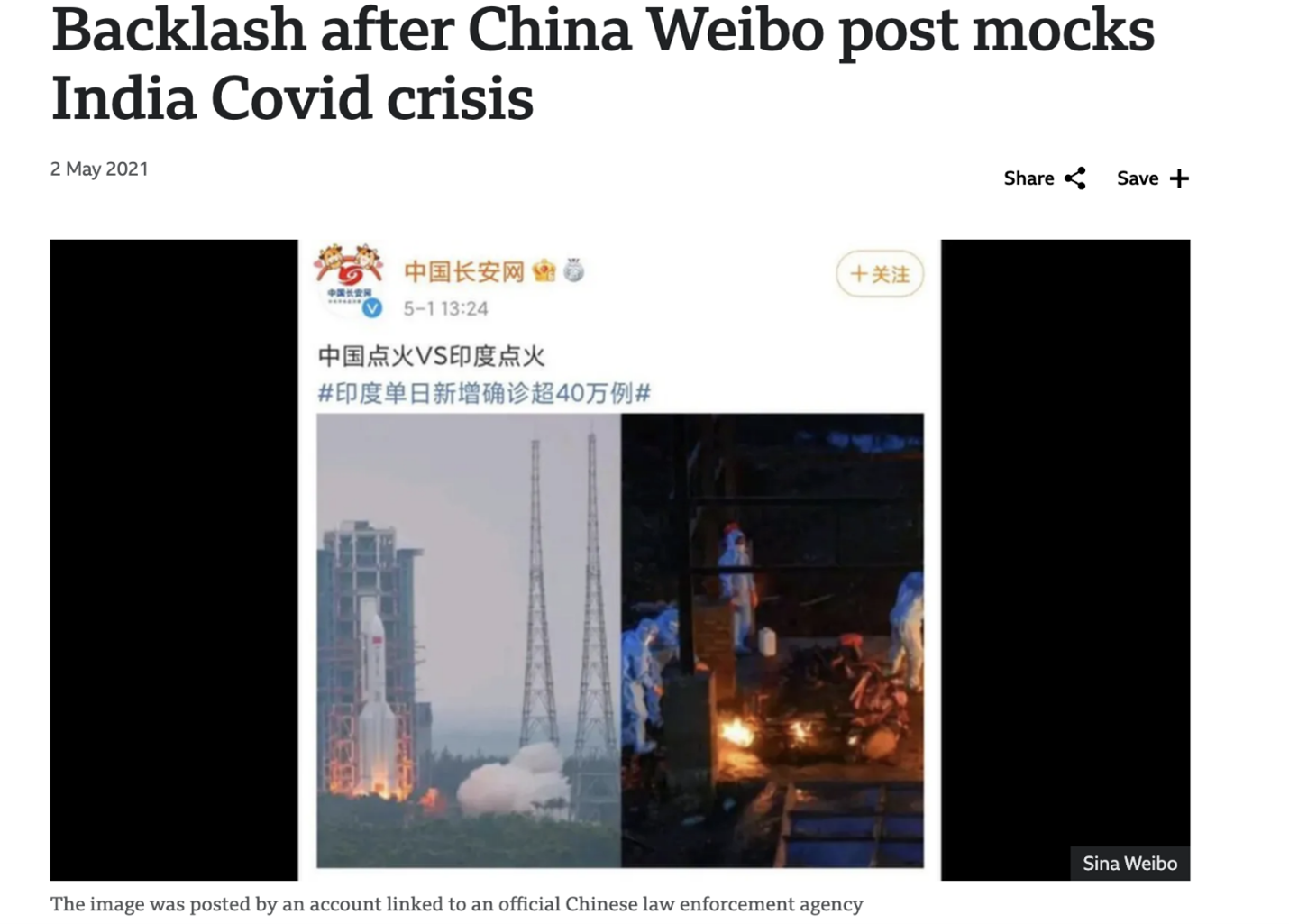

As the COVID-19 pandemic raged on in 2021, at a time when India was suffering its highest number of daily deaths, and ties between India and China had frayed due to clashes over the disputed border, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) posted a picture on its Weibo account mocking funeral pyres in India, juxtaposing them against an image of a recent Chinese rocket launch. The caption read: “Lighting a fire in China vs. lighting a fire in India” (see Figure 1). Surprisingly, the CCP post generated backlash from Chinese netizens who were appalled at the CCP’s insensitivity, and the post was promptly taken down and followed by announcements of Chinese support for India. The messages of understanding for the Indian people appeared to be primarily driven by Aamir Khan’s immense stardom in China. Weibo users noted that Khan was among the first to express support for China during the early phase of the outbreak. On other platforms, such as Zhihu (Chinese Reddit), audiences had expressed deep empathy for Indians and Khan when he contracted COVID-19 a few months earlier, hoping “that Aamir Khan will recover soon, that 1.3 billion Indians will achieve collective immunity after vaccination as soon as possible,” underscoring Khan’s impact in shaping audience empathy during the next phase of the pandemic.

Figure 1: Source: BBC, May 2021

The quote above encapsulates the idea of soft power created by Khan’s stardom in China, which operates beyond the confines of the nation-state. When political scientist Joseph Nye initially proposed the concept of soft power, he defined it as nations’ abilities to create attractions through media, products, and other means that paint the country in a positive light for foreign publics. The process of creating those attractions, in the traditional view, remained state-centric or initiated by the state. I argue that within the broader realm of cultural diplomacy, film stars can function as non-state actors with the ability to exceed the limits of the nation-state. The case of Khan in China, therefore, is notable because his stardom existed outside of state-centric efforts on both the part of India and China.

Khan became popular in China due to the pirated circulation of his film 3 Idiots. The film was first screened at the Hong Kong International Film Festival in 2010, garnering word-of-mouth publicity that led to a Beijing International Film Festival screening. Circulation through informal piracy networks finally culminated in a theatrical release. When Khan and others became aware of the phenomenon, efforts were made to formally release the film in China, garnering widespread acclaim. However, Khan is but one contemporary example. From Amitabh Bachchan, whose prodigious stardom led to a pause in fighting from the mujahideen while he was filming Khudagawah in Afghanistan, to Shah Rukh Khan, whose song “Kal Ho Na Ho” was re-enacted by Michael Steiner, the German Ambassador to India (2012-15), Indian film stars have remained at the helm of cultural diplomacy and a conduit for soft power. So, if the state is not actively involved, how does this come about?

In my book, Networked Bollywood: How Star Power Globalized Hindi Cinema, I argue that certain male megastars possess star switching power. I define star switching power as the ability of some stars to exceed the confines of their networks and create connections where none existed before, allowing them to create inroads into new markets for Hindi film in diverse regions ranging from Azerbaijan to Germany. The metaphor of a switch is productive here because it helps us visualize how stars, much like electricity buzzing through a circuit, illuminate new connections and networks.

Star switching power has two central components. The first is the commonly possessed affective power, which is the star’s ability to move us emotionally through on-screen and off-screen personas. We are more familiar with this kind of power and tend to label it stardom. The second component of star switching power is a direct, effective power possessed only by some stars, predominantly male. This power is derived from and inflected by the star’s socioeconomic, political, and industrial clout as well as their class, gender, and caste. Simply put, effective power elaborates the kind of direct industrial and sociological power stars possess as important businessmen, producers, and owners of big production companies, in addition to the elite class and gender-based institutional and political networks they can access. Both the affective and effective powers come together to help a star be a “switch” and turn on new connections, which enables the industry to exceed the confines of its current spheres of influence—industrial and geopolitical—and break into new non-traditional markets for Indian cinema.

For instance, Shah Rukh Khan (or SRK, as he is popularly known) is a male megastar who possesses excessive affective power. At the same time, he is the owner and proprietor of one of Bollywood’s biggest production companies, Red Chillies. Through Red Chillies, SRK was able to release his film Kal Ho Na Ho on the German TV channel RTL2, which drove online fandom for the star in what was otherwise an unexplored market for Bollywood films. Following the success of the movie, German fans started an online forum that led to a magazine dedicated to the star. This fan endeavor has since evolved into a full-service Bollywood agency that now publishes magazines and hosts podcasts and film events. Through SRK’s star-switching power, the German market materialized for the rest of the industry without any deliberate state efforts. The phenomenon eventually fed back into official diplomacy in 2015 when Ambassador Steiner created the dance performance video based on “Kal Ho Na Ho” that also featured former Indian External Affairs Minister Salman Khurshid.

The idea of switching and illuminating a new circuit is generative because this metaphor lets us see how some of these connections are not entirely predictable, and their impact is hard to measure directly. However, they all culminate in the male megastar being both a catalyst and a switch that turns on connections. In this way, Bollywood stars bring together two different forms of power: the first is experienced through the feeling created by their star personas and the second is through institution building as proprietors of major production companies that possess network-making power. This culminates in their influence in India and abroad through the diaspora or non-Indian audiences, including Afghanistan, the Soviet Union, and elsewhere.

The male mega star’s switching power became the mainstay of Bollywood’s globalization, in part, because of the Indian state’s apathy toward popular cinema and filmmaking since independence. In the words of Indian film scholar Aruna Vasudev, mainstream films were treated by the state and cultural elites at best as a plebian pastime and, at worst, as “an avoidable social catastrophe.” In this context, star entrepreneurs existed as intermediaries between the state and the industry, where they marshaled their switching power in sociocultural and diplomatic contexts to create leverage with the state. Within the Indian diplomatic parlance, cinema was considered a plebian mass culture that was of a lower status than Indian classical dance and music. Thus, the Indian Council of Cultural Relations (ICCR), an institution responsible for cultural exchanges with other nations set up by the government in 1950, primarily preferred the idiom of classical dance and music as “high culture.”

Stars and films, particularly mainstream Hindi films, stayed outside the purview of diplomatic exchange. This is unlike equivalents in countries such as China or Russia that employ films directly funded or supported by the state to project ideological or political narratives or countries like the US or South Korea, which rely heavily on their popular entertainment industries to project soft power and support them in direct ways, in part, by bundling them with other exports. Recall early UNESCO studies that pointed to one-way flows of American TV shows (particularly entertainment) to the rest of the world—a flow structurally rooted in the easy availability of American TV made possible by President John F. Kennedy’s export policies that positioned Hollywood-produced TV and film content across the globe as a natural extension of US economic interests and as a way to increase exports. Consequently, TV shows like Dallas (1978-1991) became the exemplars of American cultural domination. In contrast, India’s soft power, via its mainstream film industry and charismatic, entrepreneurial stars, has been accidental, a happenstance, to be more precise.

To elaborate, when India first established diplomatic relations with China on April 1, 1950—the first non-communist/socialist nation in Asia to do so—Vijayalakshmi Pandit, a diplomat, politician, and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s sister, was tasked with leading India’s cultural and goodwill mission to China. The visit produced a quandary because, as Pandit noted, “Chinese officials had expressed a strong and repeated desire to see a full-length feature film depicting Indian social and economic conditions.” The insistence on films is essential to unpack because, for Mao, cinema held a different function. For Mao, films were a way of educating, indoctrinating, and creating political myths through cinematic symbolism. The Indian officials struggled to find a suitable film because popular Hindi films were deemed “unsuitable,” the very “dregs of society” (film critics Aruna Vasudev and Chidananda Das Gupta’s writings on state perceptions and ideas about Indian cinema provide more on this topic). Eventually, Raj Kapoor’s Awaara and V. Shantaram’s Marathi film Amar Bhoopali were selected. The exchange was momentous because Awaara was later hailed as Mao’s favorite film. Even so, it was short-lived because of eventual conflicts between India and China.

Bachchan’s stardom in Egypt narrates a similar story of star affect and cultural diplomacy. Unlike other parts of the Middle East where Indian cinema made its way through circuitous non-state networks, Egypt stood out as a notable exception because Gamal Abdel Nasser, the second president of Egypt, was Nehru’s main ally in his call for non-alignment during the Cold War. As a result, some form of formal film exchange existed between the two countries, with an Indian-Egyptian film agency (al-Wikala al-Misriyya al-Hindiyya li-Tauzi‘al-Aflam) as the main distributor. NAM ties notwithstanding, this changed drastically when Anwar Sadat succeeded Nasser in 1970. Apart from ideological distancing due to Cold War alignment with the US, Sadat thought that Indian films were detrimental to the local Egyptian industry and morality. Bachchan and his films, however, remained an interesting anomaly and continued to be screened because of his widespread popularity. When Bachchan visited Egypt in 1991, he was welcomed by none other than Jehan El-Sadat, Anwar Sadat’s wife.

In each of these cases, star switching power helps the stars exceed the limits of the nation-state and become important non-state actors in cultural diplomacy. Through fans, the emotional draw and the connection created by their cinema (affective economies of fandom), stars create and have historically created positive perceptions about India and cultivated soft power. It also shows how the audience’s emotional dedication to stars such as Aamir Khan in China and other stars in the past, which I term affective investment in individual social actors, helps and has helped define these attractions, creating a cultural resonance rooted in shared experiences and developmental realities. Cinematic cultural diplomacy is an outlier in the Indian practice of public diplomacy because it is not directly carried out by the state. It is, therefore, curious why the Indian state has been veering between parallel “high taste and culture” art cinema of yore or, in the contemporary context, performative gestures and photo opportunities, but has never quite strategically leveraged its popular mainstream film industry and stars in geopolitics.