The Decrease in India’s Air Pollution During COVID-19

Amidst the devastating COVID-19 pandemic, a rare positive has been a significant global decrease in air pollution levels. Primarily, experts have measured nitrogen dioxide (NO2), one of the six major air pollutants (in addition to particulate matter, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, ground-level ozone, and lead). NO2 has, like most other gases, natural and human sources. Natural sources include lightning, oceans, and volcanoes. However, in urban regions, natural sources of NO2 account for a small fraction of total NO2 levels; according to a 2005 report by Australia’s Department of the Environment and Heritage, natural sources of NO2 only account for 1 percent of overall NO2 levels in cities. Human activity is almost entirely responsible for NO2 emissions in urban regions, with road transport being the number one cause. Planes, power plants, and ships, all of which burn fossil fuels, are also significant human sources of NO2. Given this, it’s unsurprising that during the stringent global lockdowns, NO2 levels have dropped significantly in urban areas, especially in India’s densely-populated cities.

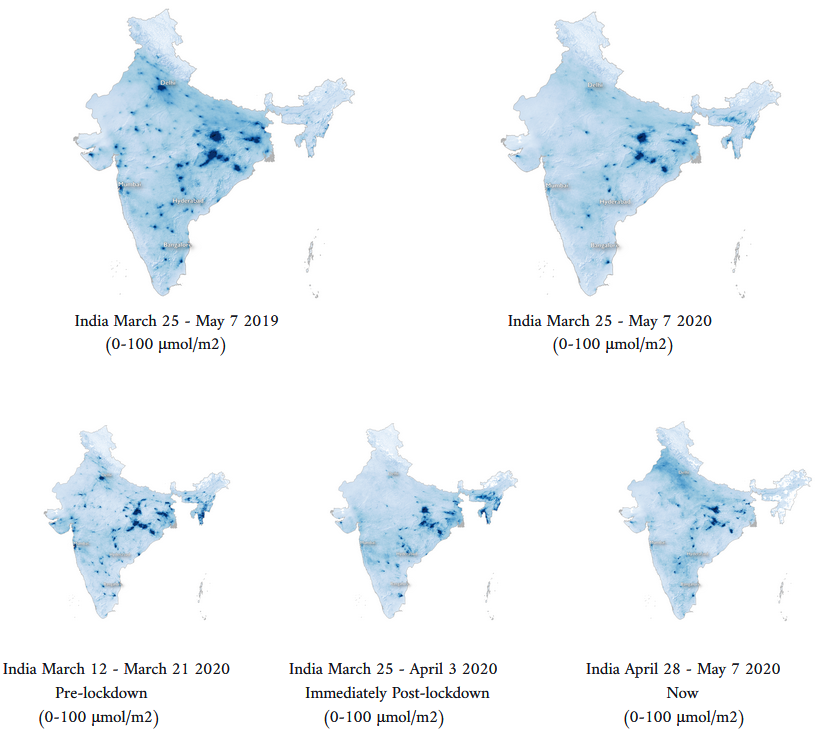

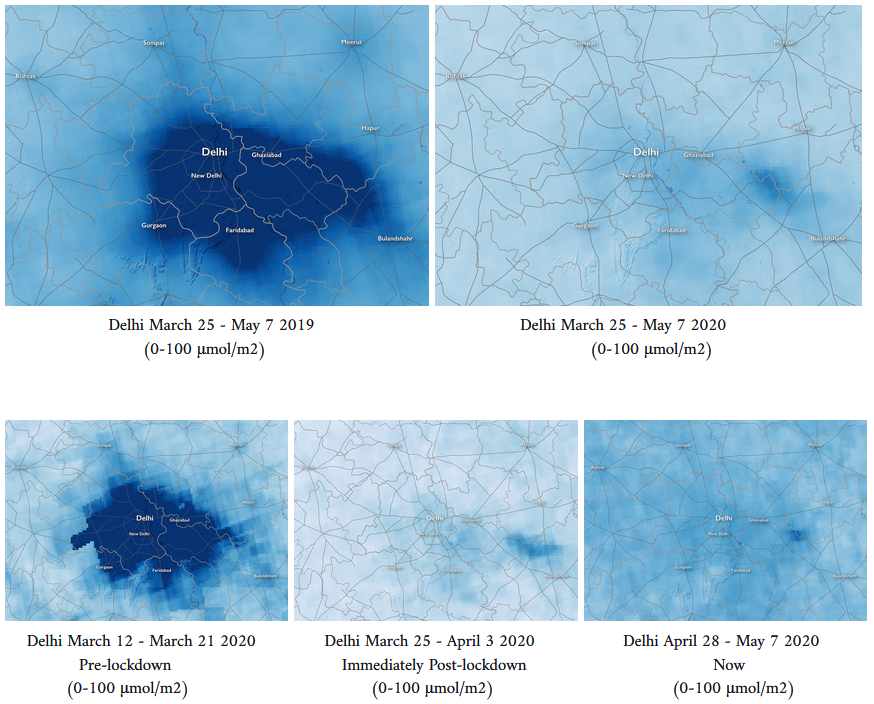

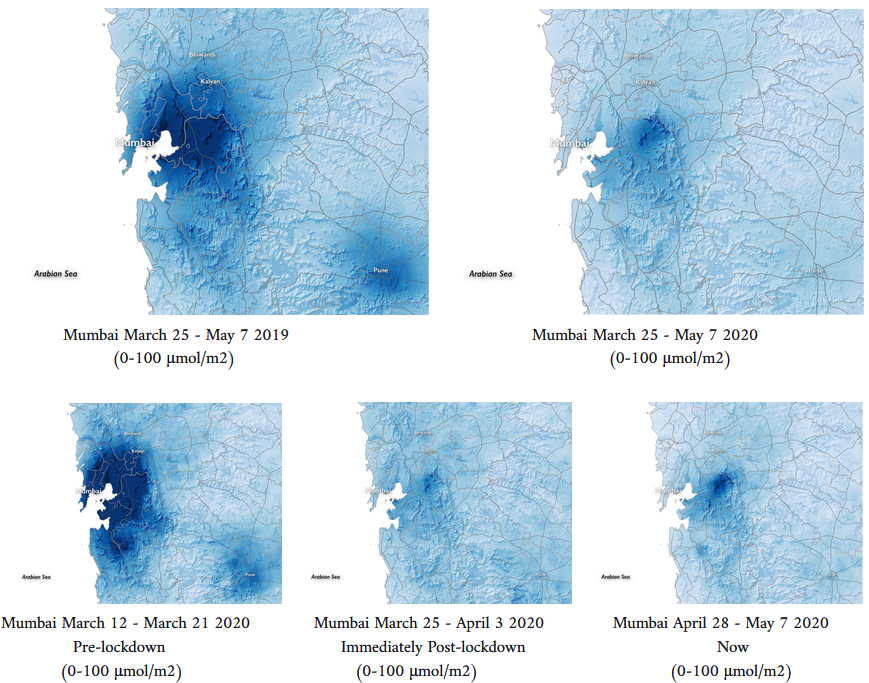

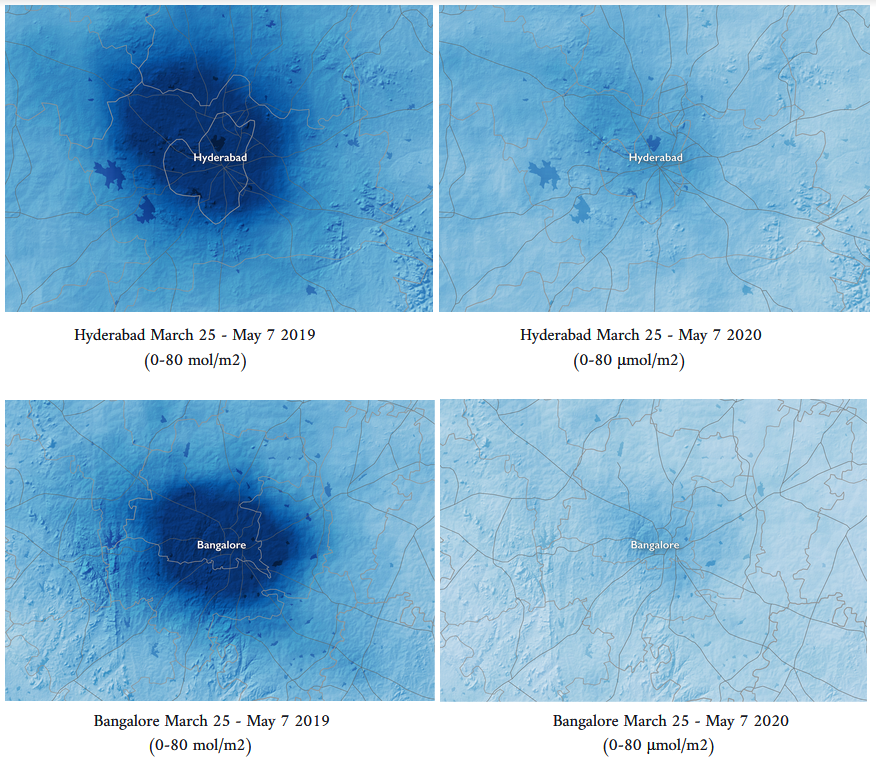

Satellite imagery from the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel 5P satellite measures NO2 levels globally. These measurements accurately reflect emissions sources because unlike other gases that can travel a significant distance from where they’re emitted, NO2 has a short lifespan and dies before it can move very far. In other words, if the Sentinel 5P satellite captures a hotspot of NO2 over Delhi, it’s highly likely it was emitted from within Delhi’s vicinity. Satellite imagery is, therefore, a highly reliable tool for measuring NO2 emissions, especially if data with high levels of cloud coverage is excluded.

The global decreases in NO2 levels were first seen in China, where levels plummeted dramatically following the strict quarantine measures enforced in late January. As nations in Europe and North America followed China’s lead in late February and March, similar trends have been observed globally. India’s nationwide lockdown, in particular, has had stunning effects on air pollution levels.

With citizens quarantined at home, road transportation and power plant operation have come to a grinding halt, and pollution levels across the country, especially in typically smoggy cities, have fallen to dramatic lows.

The NO2 measurements below are in Delhi’s metropolitan area, where pollution levels in the nation’s largest city have dropped most dramatically; NO2 levels from March 25 (the day quarantine began) to May 2 have averaged 90 µmol/m2 compared to 162 µmol/m2 from March 1 to March 24. In 2019, NO2 levels from March 25 to May 2 were also far above this year’s levels, averaging 158 µmol/m2.

In the NO2 measurements below in Greater Mumbai and Navi Mumbai, a similar trend has been observed as NO2 levels from March 25 to May 2 averaged 77 µmol/m2 compared to 117 µmol/m2 from March 1 to March 24. In 2019, NO2 levels from March 25 to May 2 averaged 122 µmol/m2.

In nearly all other big Indian cities, similar drops in NO2 levels are apparent, highlighting the national scale of India’s lockdown.

The country-wide drop in NO2 emissions during this lockdown has significant immediate consequences. Exposure to high levels of NO2 has substantial detrimental effects on human health. Short-term exposure to high levels of NO2 can result in worsened coughing, aggravation of existing respiratory diseases (asthma), and hospitalization, while longer-term exposure can lead to the development of asthma and increase one’s susceptibility to respiratory diseases. It makes sense, therefore, that experts are finding significant links between long-term exposure to high levels of air pollution and increased COVID-19 death rates. Many researchers have hypothesized that the drop in air pollution levels may currently be saving a significant amount of lives, not only by reducing individuals’ susceptibility to COVID-19, but also by preventing some of the world’s seven million annual deaths due to air pollution exposure. Still, the dangerously high levels of NO2 in many urban areas before COVID-19 has likely resulted in far more COVID-19 deaths compared to the lives saved by this current drop in emissions.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent decreases in air pollution levels due to quarantine have illuminated a severe issue regarding ongoing high levels of air pollution. The terrifying reality is that despite human activity essentially coming to a complete standstill, current estimates suggest that carbon dioxide (CO2) levels will only decrease by roughly 5.5 percent in 2020 compared to 2019. To put this in perspective, to meet the goal of limiting the global increase in temperature to 1.5 degrees celsius, which many experts agree would stave off the worst effects of climate change, global CO2 emissions would need to decrease by 7.6 percent each year. Similarly, air pollution and NO2 levels are expected to rise to their normal unhealthy levels when quarantines are lifted.

It’s crucial that when India’s lockdown inevitably ends, and people return to their normal routines, they aren’t forced to revert to their old behaviors. To make the current drops in air pollution levels permanent, serious policy change needs to be enacted. The reduction in road transport and the correlated decrease in air pollution have highlighted that gas-powered cars are key drivers of air pollution. Electrifying transport, expanding public transportation, building more bike lanes, and finding other ways to incentivize people to ditch their cars would dramatically reduce India’s emissions from its primary human source of air pollution. It’s also crucial that these electric vehicles, and India’s cities more broadly, are powered by clean sources of energy rather than fossil fuels.

It’s ironic that this devastating respiratory virus has illuminated another respiratory crisis. May India make the recent decreases in air pollution that have provided a glimmer of hope during these difficult times permanent rather than a temporary glimpse at what’s possible.

James Poetzscher is the founder of greenhousemaps.com, and a student interested in atmospheric chemistry and satellite data. His maps have been featured in a variety of notable articles.

India in Transition (IiT) is published by the Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI) of the University of Pennsylvania. All viewpoints, positions, and conclusions expressed in IiT are solely those of the author(s) and not specifically those of CASI.

© 2020 Center for the Advanced Study of India and the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved.