Electoral Quotas as a Tool for Fighting Exclusion and Discrimination

The use of electoral quotas, such as reserved seats in parliaments or candidate quotas, has become increasingly common, and is usually defended on the basis of various assumed positive long-term effects. However, in most countries, it has been hard to identify such effects, partly because the policies have not been in place long enough.

Experiences from India – the country with the most extensive and longest-established electoral quota systems – can, therefore, help to inform discussions about what to expect from quotas in the long run. From September 2010 to April 2011, I conducted more than a hundred interviews (mainly in Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Karnataka) with politicians and civil servants about the electoral quota system in India. Drawing on these interviews as well as various quantitative data sets, I have studied the long-term consequences of the electoral quotas for the Scheduled Castes (SCs). Since India’s first post-independence elections in 1951, this large minority group has had reserved seats in the lower house of parliament and in the state assemblies, proportional to their share of the population in each state (16 percent on average).

What has happened after more than 65 years of electoral quotas for SCs? My research indicates that these quotas have played an important role in breaking down social hierarchies in India by helping reduce caste-based discrimination both in politics and in society at large. Contrary to what one might expect, this is not because they have led to more group representation – SC politicians working particularly for SC interests – but rather because they have helped to integrate SC politicians into mainstream politics.

Design and Implementation

Quotas are often spoken of as one type of policy, but they may be designed in many ways. Broadly speaking, quotas can be divided into systems where quota politicians are elected by (and answerable to) voters from only their own group (such as Māori politicians in New Zealand) and systems where they are elected by a similar electorate as other politicians (such as candidate quotas for women). In India, these two types of quotas have been referred to as “separate electorates” and “joint electorates.”

The Indian Constitution grants SCs and Scheduled Tribes (STs) reserved seats with joint electorates, meaning that in reserved constituencies, only SCs/STs may run for election but voters from all groups can vote for them. The design of this system was the result of a compromise between SC representative Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, who wanted separate electorates, and Mohandas Gandhi, who wanted no quotas at all.

Between 1951 and 1961, the reserved seats for SCs and STs were implemented as extra seats in some constituencies (electoral districts). But since the Two-Member Constituencies (Abolition) Act of 1961, each Indian delimitation has assigned constituencies to be either general (open to all candidates), or reserved for only SC or ST candidates. This reservation policy has been strictly implemented and has brought thousands of SC and ST politicians to power across India.

The Delimitation Commissions of India have been very systematic in selecting reserved constituencies, trying to choose places with a high proportion of SCs or STs, but also to spread the reserved constituencies out geographically. However, since SCs are in the minority across most of India, they are also usually a minority in the constituencies reserved for them. In practice, this means that most SC politicians are elected by a majority of non-SC voters. By contrast, ST-reserved constituencies tend to have an electorate consisting of a majority of ST voters.

Agents of their Parties, Not of their Group

With a fixed number of seats set aside for SCs and STs, all the main parties have wanted to win those seats and have fielded candidates in reserved constituencies. Comparison of the percentages of seats held by different parties in SC-reserved and general constituencies over time shows that slightly fewer SC politicians have run as independent candidates, and slightly more of them have run for India’s main right-wing party, the BJP. The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), an ethnic party running on an SC platform, has won a large share of both general and SC-reserved constituencies in Uttar Pradesh – India’s largest state – since the early 1990s, but in terms of patterns for all of India, their share of SC seats has not been very large.

SC politicians have not only run for the same parties as other politicians, they also tend to run on the same party platforms. As most of their voters are non-SCs, most of the SC politicians I interviewed made it clear they saw themselves as representatives of their parties and their voters, not of their specific group. The fact that SC politicians are similar in profile to other politicians, and do not try to work more for their group than do other politicians, has also meant there are few differences in the types of political decisions they make. In fact, data from 1971 and 2001 show that there has been no systematic difference in development patterns in SC-reserved and general constituencies over time – neither less development overall, nor more development for SCs.

Reduced Discrimination

SC politicians used to be somewhat less experienced and educated than other politicians, but these differences have evened out over time. Looking at survey data, there are also no systematic differences in how voters feel about SC politicians and other politicians. Voters who have experienced having an SC representative are more positive to SCs as politicians, and they report less caste discrimination in their communities. Studies of the effects of quotas for SCs in village-level politics have also found favorable effects on inter-group interaction.

SC politicians I interviewed made it clear that, although there is still considerable discrimination of SCs in many parts of India, people generally treat them with respect. Several of my respondents mentioned they thought they would not have been able to get into politics without the quotas, but that once they had gained political experience and had the chance to prove themselves, they were taken seriously by their parties and their voters.

SC Reservations as an Entry-Point for Women

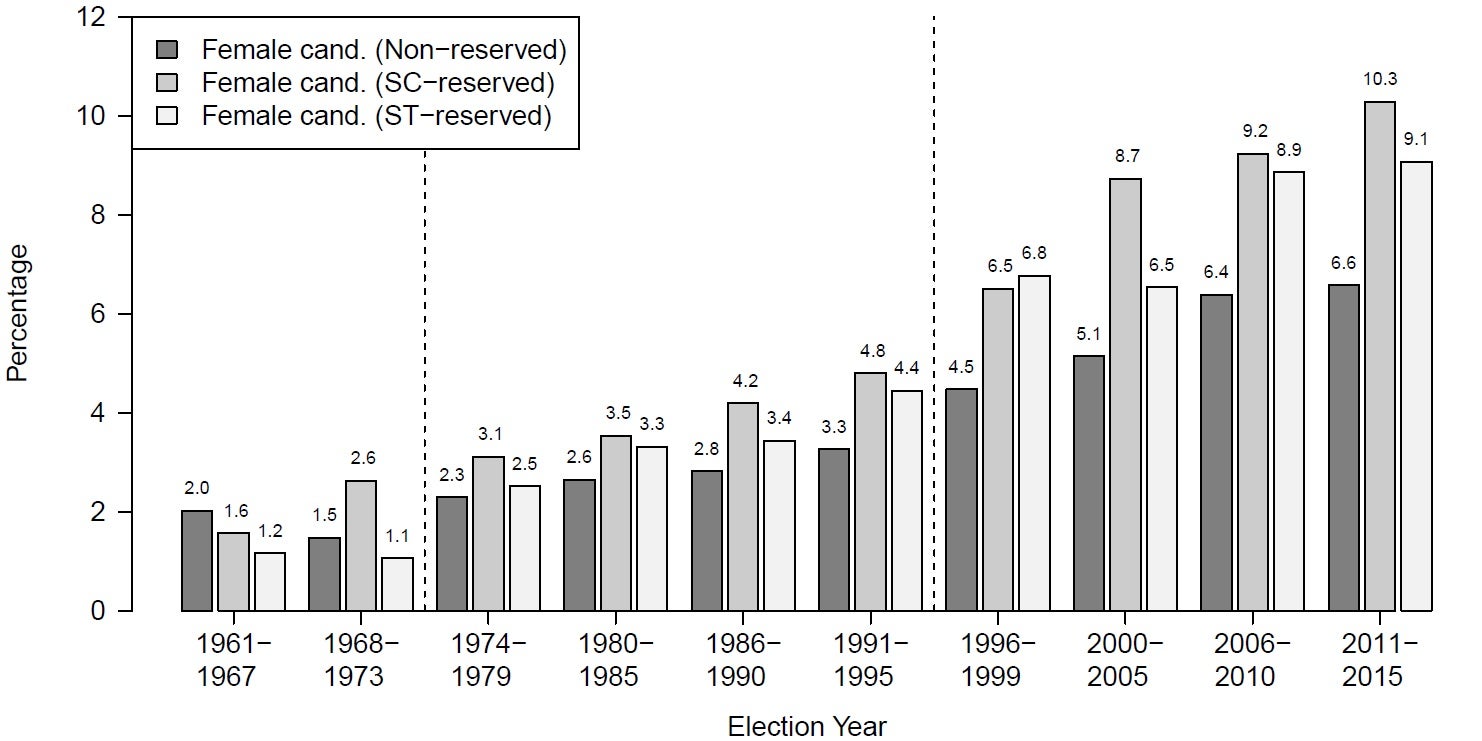

The quotas for SCs and STs have also served as an entry-point for women in Indian politics. Despite an informal party quota for women in the Congress Party in the 1950s and 1960s, women constituted only 3 percent of the candidates in parliamentary elections and 2-3 percent of the candidates in the state assembly elections until the early 1990s. However, the percentages of women fielded in constituencies reserved for SCs and STs have been higher than in general constituencies. The figure below shows this difference has also grown stronger over time.

Figure taken from “Competing Inequalities? On the Intersection of Gender and Ethnicity in Candidate Nominations in Indian Elections,” Francesca R. Jensenius. Government and Opposition 51:3 (2016)

This pattern may be the result of political parties nominating female candidates at the expense of what are sometimes talked of as their “least powerful” male politicians: SC and ST men. However, it can also be seen as evidence that the political environment in reserved constituencies is more open to female candidates. As reserved constituencies are somewhat less competitive and also less dominated by “money and muscle” politics than other constituencies, they seem to have become a more accessible point of entry for female politicians.

Francesca R. Jensenius is a Senior Research Fellow at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. She works on issues of inequality and representation for women and minority groups. Her forthcoming book, Social Justice Through Inclusion: The Consequences of Electoral Quotas in India, is about electoral quotas for SCs in India.

India in Transition (IiT) is published by the Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI) of the University of Pennsylvania. All viewpoints, positions, and conclusions expressed in IiT are solely those of the author(s) and not specifically those of CASI. IiT articles are re-published in the op-ed pages of The Hindu: Business Line. This article can be read here.

© 2016 Center for the Advanced Study of India and the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved.