How Wide is the “Sink of Localism” in India?

Even a beginning student of rural India with only a passing familiarity with its complex social organization can wax eloquent about one stylized fact—the near-perfect segregation of residential space by caste and religion. Introductory textbooks have immortalized spatial segregation as a constitutive feature of social life in agrarian India. When Ambedkar famously characterized the Indian village as a “sink of localism,” and a “den [of] narrow-mindedness,” he was partly railing against such spatial segregation in the Indian countryside.

Figure 1: Amminabhavi, Dharwad District, c. 1950. (Digitized and remastered by authors using original sketch from Spate and Learmonth, 1954, p. 200)

Generations of detailed ethnographic research has documented how residential space in rural India is not only segregated, but actually mirrors the hierarchical ordering of caste groups. Figure 1 depicts residential segregation in Amminabhavi, situated on the outskirts of the city of Dharwad in Karnataka, and made famous by Spate and Learmonth (1954) as the quintessential example of spatial organization in village India. This large village shows how Dalits (the formerly “untouchable” caste groups shown as “Harijans” in the original figure) are consigned to the periphery of the village. The dominant landholding castes occupy the center of the village. Other worker castes in the figure—Talwars, Shepherds, and Washermen—are also relegated to the spatial margins. The village headman and his kin occupy the best land parcel and live in a palatial “manor house.”

Even as cartographic accounts detailing Amminabhavis around India have proliferated, we do not yet have a systematic quantification of the degree of segregation rural India. Consequently, quantitative studies of rural political economy are besieged with an important “missing variable.” While the actual extant of intra-village segregation remains unknown, the Indian national census data records the presence of multiple hamlet clusters in select districts across the country.

Our summary is derived from preliminary findings of an ongoing project to develop the first ever largescale quantitative measurement of intra-village spatial segregation in India. We use micro-data from a survey conducted by the Government of Karnataka in 2015 (GOKS) to measure intra-village segregation. GOKS represents the first census-scale enumeration and coding of detailed caste (jati) and religion data since 1931, and the first ever micro dataset that allows for a quantitative characterization of intra-village spatial segregation. The data includes demographic information for all rural residents in Karnataka (approximately 36.5 million residents) from over 26,000 villages.

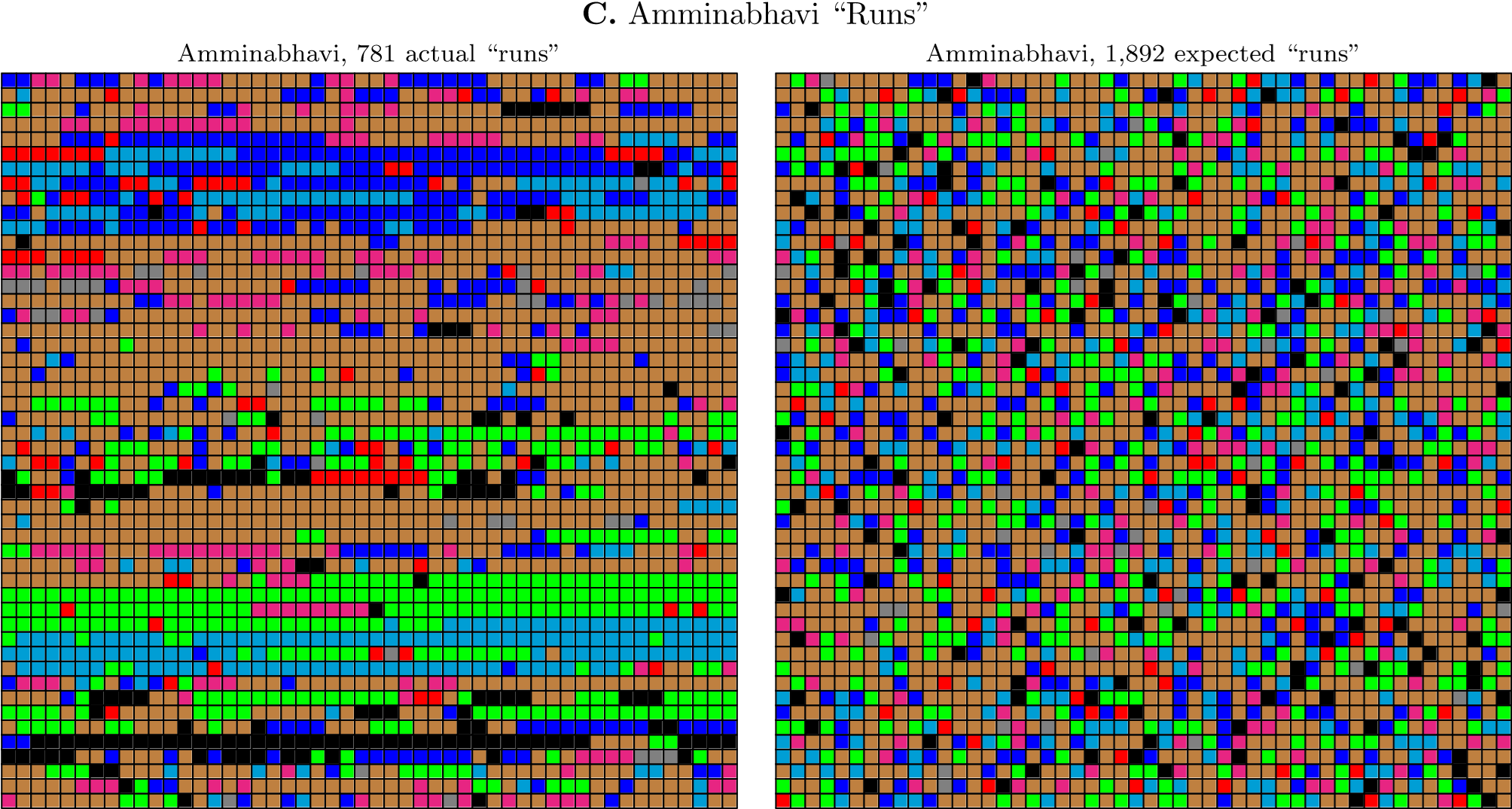

We measure intra-village segregation by comparing the actual spatial arrangement of households in a village with the hypothetical case where the households are randomly distributed in the village. Figure 2 describes how we measure intra-village spatial segregation. Panel A of the figure depicts an actual village hamlet in the GOKS dataset. The forty households in this village are drawn from four different jatis. Panel B shows these households arranged in a random order. To compute intra-village segregation, we simply compare the “runs,” or unbroken sequence of households that share a social identity in the actual village with the hypothetical random ordering.

We adapt the well-established “runs test” metric that has previously been used to measure street-level micro-segregation to more than two categories to account for the multitude of jati and religion groups in a village. The actual village has nine “runs,” while a random arrangement of the same forty households corresponds to twenty-one expected runs. The fewer the actual “runs” relative to the hypothetical random organization of space, the greater the measured value of segregation.

Figure 2: Wald-Wolfowitz Micro Segregation. Amminabhavi representation in Panel C uses the eight-fold administrative mapping of endogamous jati and religion groups. Halli in Panels A and B use endogamous jati and religion groups. Each square represents an individual household in all three panels. The 2,500 houses in the Amminabhavi grid are represented row-wise. Authors’ computation (data from GOKS).

Panel C in Figure 2 shows the 2015 spatial distribution of households in Amminabhavi as recorded by GOKS (we have shown the eight-fold administrative mapping of jatis). Even as Amminabhavi is on the cusp of being designated “urban,” its spatial demography has remained remarkably stable—seventy years after it was first immortalized as the exemplar of spatial organization in village India.

Our intra-village segregation metric is measured on a 0–1 scale with a 0 indicating perfect integration and 1, perfect segregation. Figure 3 shows the distribution of this intra-village (micro) segregation metric across all villages in Karnataka for jatis, census groups, as well as religion. The boundary between the “touchables” and “untouchables” is especially stark as seen by a high degree of segregation between SCs, STs., and others (census groups). As a point of reference, Amminabhavi in Figure 3 has an intra-village micro segregation score of approximately 0.55. The extent of intra-village segregation in Karnataka is greater than the local black-white segregation in the American South that continues to influence residential patterns to this day.

Figure 3: Distribution of Micro (intra-village) Segregation for jatis, census groups and religion in Rural Karnataka. 0 indicates perfect integration and 1, perfect segregation. Figure reproduced from Bharathi et al. (2020).

Our analysis also shows that the extent of intra-village segregation is uncorrelated with other metrics used to measure demographic diversity, so that not accounting for such segregation can potentially bias extant quantitative characterizations of rural political economy in India. Limited evidence suggests that accounting for intra-village segregation is important for characterizing India’s rural political economy. Local public goods placement, or even hydro-geological distribution of groundwater resources within a village intersect with intra-village segregation.

Beyond the political economy of rural India, the measurement of “social distance” has been one of the central founts of modern social sciences. For example, Georg Simmel argued that the stranger is, above all, a product of prevailing social distances that are explicitly spatial—the “geometry” is a constitutive feature of social distance. In societies with clearly defined status ranks, the classical relationship between contact and prejudice is shaped by Simmel’s “geometry.” If inter-group solidarity is tied to inter-group contact, our analysis shows that spatial segregation remains one of the most significant barriers.

This article is based on the forthcoming Contemporary South Asia article: “A Permanent Cordon Sanitaire: Intra-Village Spatial Segregation and Social Distance in India.”