Local Governance and Decentralization in Karnataka

About the Speaker:

Uma Mahadevan is a senior civil servant in India, currently posted as Principal Secretary, Panchayat Raj in the Government of Karnataka. She has worked in major sectors in the Central and State Government including planning, agriculture, education and health. Most recently, she has worked as Principal Secretary, Women & Child Development. She was a member of the working group that prepared Karnataka’s first Human Development Report.

About the Lecture:

The state of Karnataka has been an early frontrunner in decentralizing governance structures, devolving powers to local government institutions even prior to the 73rd Constitutional Amendment of India. How has this system of decentralized governance (Panchayati Raj) in Karnataka evolved since the 1980s? Using the examples of the Anganwadi program (Integrated Child Development Services Scheme) and COVID-19 management in rural areas, Ms. Mahadevan will discuss how decentralized governance can bring convergence across local state actors and stakeholders to reach the poorest who are often excluded from social welfare programs.

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Apurva Bamezai:

Okay, a very good morning to those of you joining from here in the US and a good evening to those joining us from India. I hope you and your loved ones are staying safe in these trying times, especially with the second surge. Welcome to this special virtual lecture organized by the Center for Advanced Study of India, CASI, at the University of Pennsylvania. My name Apurva Bamezai, and I'm a PhD student in the political science department here at Penn, and also will be doctoral fellow at CASI this year. I will be serving as the moderator for today's session.

We break from regular programming today to add to the wonderful lineup of academics we've had here at CASI this semester. We're very excited to have a senior bureaucrat deliver a lecture as part of the spring lecture series. Please join me in welcoming Ms. Uma Mahadevan, who will be speaking to us on the topic of local governance and decentralization in Karnataka.

Ms. Mahadevan is a senior civil servant in India, is currently posted as principal secretary Panchayati Raj in the government of Karnataka. She has worked in major sectors in the central and state government, including planning, agriculture, education, and health. Most recently, she has worked as principal secretary women and child development. She was also a member of the working group that prepared Karnataka's first human development report. We're very delighted that she has made the time to share her insights with us today.

Some of you already know this, Karnataka has been an early front runner in decentralizing governments, devolving powers to local government structures even prior to the 73rd constitutional amendment. So, Ms. Mahadevan will talk about the evolution of the system of decentralized governance in the state since the 1980s with a focus on the role of convergence at local levels in improving service delivery to the very poor.

Before we get started, just a few words about the format today. Firstly, I request all of you to mute your mics for the duration of the talk. She'll speak for about 25, 30 minutes, and then we'll open the floor for questions for the next 25 minutes or so. If you wish to ask her a question, please send me a direct message so that I can compile a list of questions. Please keep your questions short, brief, and only unmute yourself when I call upon you to ask your question during the Q&A session. I would also request that we refrain from using the chat box for comments during the lecture as this can be very distracting.

Okay, all right. Without further ado, welcome, again to CASI, Ms. Mahadevan. The floor is now yours.

Uma Mahadevan:

Thank you. Thank you to CASI for having me. [foreign language 00:03:13], Apurva. It's a pleasure to join all of you. Today, at the outset I'd like to just make it very clear that I'll be speaking... It's intimidating to a non-academic to be talking to a group of academics, so I'll be speaking as a practitioner and as somebody who has a very strong stake in decentralization on the ground. Most of my presentation is actually going to explain why that is, in the first part, where I'm going to be talking about my work not as principal secretary Panchayat, but in my earlier role as secretary in the department of woman and child development when I realized the power of decentralization working with [inaudible 00:04:09].

And the second half is going to quickly take you through some of the milestones in the evolution of Panchayat in Karnataka and what's possible. Very, very quickly, and then we'll move to questions. I have a few slides. I will just try to share the screen.

Okay, so as I said, this is a realization that came to me not in my current role, but in my previous role when I was in the department of woman and child development working on early childhood care and development at Karnataka's network of 66,000 Anganwadis. We had, at that point, just received the NFHS, Nation Family Health Survey data had just been released. This was in 2016 and the data looked fairly concerning.

There had been a reduction in stunting, not as much as one would have liked to see. There had been a reduction in anemia among women, again, not as much as one would have liked to see and low birthweight [inaudible 00:05:36]. But what was really alarming was that wasting had gone up and that child stunting was still at 36%, which was really alarming in Karnataka. Being one of the very large drought-prone states in the country, the second most drought-prone area after Rajasthan, it seemed imperative that we should do something about this as quickly as possible. And so one of the things that we did, among many things, many interventions, was that we came up with a scheme which was basically a hot meal program, which would then layer health interventions. These are just [inaudible 00:06:19] see the components of the hot meal. It doesn't really matter.

But the reason why we said that it would be a hot meal was that this was a process change in what was being delivered. Women were getting dry rations once a month from the Angawandis, and there were four kinds of problems with it; pilferage and even quality shared within the family. And even if the women got to eat it themselves, the quantity was just not enough. So we decided to replace it with a hot meal program which had already been tested and proved effective in neighboring states of Telangana and Andhra, as part of the housing what's called 1000 day approach, I'm sure you are aware of it; the first 1000 days in the life of a child.

One of our intentions was to try and break the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition. Because nearly two thirds of low birthweight babies were found to have intrauterine growth retardation. And if we could enable malnourished mothers to have better nutrition during pregnancy, we felt that we could break the intergenerational cycle of nutrition. These are actual pictures from our Angawandis. And I'm happy that we were able to use these pictures in this presentation.

The other thing that we did was, of course, to realize that... And I'll explain in a little bit why all of these nuances are important for decentralization. The other thing what we realized was that no single intervention will work as much as a nuanced lifecycle approach. So we needed to address child marriage, we needed to bring in an amendment to Child Marriage Act. We also needed to do a huge program of awareness about it, we needed to address stunting, wasting, and undernutrition, all of which require different kinds of interventions.

And we also needed a multi-sectoral approach, which meant that we also needed to address issues like the fact that the scale of the program itself was integrating, to start with, 66,000 Anganwadis, 5% of them were mini Anganwadis which had just one worker, the others had two, a coverage of more than 5 million, a workforce of 1.25 lakhs on the ground, extended hours 9:30 to 4:00. But we also needed to solve working conditions of the Anganwadis workers. They were frontline workers, their honorarium, their working conditions, their leave, their medical cover. And we needed to address the fact that we needed to build buildings, we needed to build toilets, we needed to find space for gardens for children to play. So a multi-sectoral approach.

We also needed to have direct nutrition interventions, so milk, eggs, additional therapeutic allowance, sprouts, and lunch for all children. Severely malnourished children got additional eggs, moderately malnourished children in five districts got additional eggs. Other children got two eggs twice a week all over the state. We needed to do height measurement, we needed to measure mid upper arm circumference. So these were the nutrition interventions and the monitoring. This shows you a little bit about not only how large scale the program was, but also how complex it is on the ground.

And this was our hot meal program where he brought in this layer nutrition program, launched it after a pilot for operational issues across the state in 30 districts with 800,000 women participating in this. This picture is a favorite of mine because gender issues and the ways in which pregnant women eat is always supposed to be this evil eye that affects pregnant women [inaudible 00:10:19] them eat. And so, in the first week of our program, we found that women were facing the wall all in different directions and eating. But within a week, they felt so foolish and awkward that they started turning around with each other, started to eat together.

And these are, again, some of the details of the program. But I need you to just look at this picture. She's a construction worker in Yadgir, little baby in her lap, but she also brought her young child who's not Anganwadi enrollment age, as in, she doesn't come to the Anganwadi, the child is just one and a half years old. But when the mother comes to the Anganwadi, the little child comes along.

The reason I'm telling you all this is that these are problems that cannot be solved or should not be solved or addressed from a state level, but need to be contextualized and quickly addressed on the ground. These flexibilities can only come if we can do these things on the ground. If there are migrant women, if there are women without a [inaudible 00:11:21], if there are women who need to bring another child to the Anganwadi for a meal, if there are women who are left out, if there are women who are brick workers, who are seasonal migrants, who are sugarcane harvesters, they are invisible to anyone other than to the Panchayati. And those women need to be brought in on the ground.

This was what we found was happening. As soon as we started rolling out the program, we found... In fact, one of the first women who came forward was a ground Panchayati member from [inaudible 00:11:55] where we rolled out the program. And she said that, "If the government is going to bring this program, I think it's excellent, but you haven't provided for coconut. And women won't like the taste of the food without coconut. And so I will provide coconut from my field." So that's what she started to do.

There was another lady in Belgaum who said that, "You need to eat the rice with pickle, and gooseberry pickle is really good for pregnant women. So let me give you gooseberry pickles. I've made homemade gooseberry pickles." So this is what she did. She's a grandmother from Belgaum. So Panchayat members as well as other women from the community coming forward.

We also had to build a lot of flexibility into the program. This is an Anganwadi kitchen, where you can see that there is a lot of labor involved in this additional work of providing an extra meal to women rather than providing the dry rations to their homes. And so what we did was we decentralized the local issues, but we insisted that Anganwadi should have, instead of a single burner stove, a double burner stove, two pressure cookers, two sets of gas cylinders, and so on and so forth.

Invitations were issued by the Panchayat to all the pregnant women, many Panchayats gave [inaudible 00:13:16] pieces, gave little bunches of flours. When breastfeeding mothers would come after the child in six months, there's a little ceremony called the [inaudible 00:13:26] ration. So Panchayats would again, give flowers to the mothers and little gifts to the babies. This was another part of the program.

The entire program, apart from just being something that we rolled out to address the problem of malnutrition, turned out to be a learning experience for a lot of us. And most of all for me, because I realized that this entire program succeeded to the extent it did. And an independent evaluation has shown that not only did it have an impact on anemia and birthweight and gestational weight gain of the women, but it also improved the mental health status. So it succeeded or had the impact it did, not only or nearly as much of us functioning as a technical department, but because the local Panchayats had taken it, owned it, and adapted it to their needs.

We found Gram Panchayat in Mandya, for example, which is the district with the lowest stunting in the state, coming forward and saying that, "If the state is providing the cookers and the gas cylinder and the vessels and the milk, we are going to provide mixers so that the children can have or the mothers can have buttermilk and [inaudible 00:14:52], and et cetera." So a lot of local innovation was happening which was really intriguing and very heartening, but also it was... I think quite all inspiring to see the kind of thought that Panchayats would put into this. They really instinctively owned the program.

A lot of interventions layered with the program; pregnancy weight monitoring, early registration, IFA compliance, calcium, deworming, the tetanus injection, ensuring that no woman was left out, bringing in a tech platform for monitoring. And flexibility in the menu, some places wanted a certain type of rice. Some people wanted to introduce millet, some people wanted to have [inaudible 00:15:41] once a week or some people wanted to have [inaudible 00:15:43] once a week. Monitoring of blood pressure, hemoglobin, migrant women.

This was, I think, the most exciting part of the program personally, because sugarcane migrants who would come... They're called sugarcane gangs who come from Maharashtra and other parts of the neighboring states to, say, Belgaum and other places to harvest sugarcane. And they work in a particular set of fields for a month. They're working there and working and working, and then they move to another field. And Anganwadi workers and supervisors actually jumping into those fields and calling them and getting them enrolled and ensuring that they and their children were covered under this program with the help of the local Panchayats, that was, again, an eye opener.

We also found that the women were forming informal social networks, the postpartum depression. Not just anecdotal, but as I said, an independent evaluation by NFHS showed very interesting results. It was like a form of social audit, but also there were Panchayats which were treating it as an effective parenting training platform that women who were married young, who didn't have the benefit, or who migrated within the state, didn't have the benefit of their social networks within their families to help them to bring up their children would get the kind of advice or the kind of support that they needed during pregnancy through these [inaudible 00:17:15] networks. So this was, again, very, very interesting.

And there was a huge sense of community ownership. We started finding that the Anganwadi was already at the heart of the community, they wanted to give uniforms to the children, they wanted to paint the Anganwadi. They wanted to provide fruits and vegetables and what have you, racks, shelves for the Anganwadi toys for the children, things like that. Huge burst of goodwill, because they realized that this is something that we need to do. They really owned the program. And until COVID came and disrupted things, and Anganwadis had to close, this was quite a remarkable sense of ownership.

We also found that certain differences between people, distances, social gaps between people, women from different communities started sitting together. We talked about how we'd not try to solve the caste conundrum in underhand ways, but we'd address it directly without being adversarial about it. So we talked to them and said that, "Your children are eating, and it's the 21st century. And are you really going to talk about the caste of the Anganwadi worker or the helper? Don't you think this idea should be left behind?"And we found a lot of, again, Panchayat members helping us with this.

Wherever we faced difficulties in counseling communities and counseling, say, mothers-in-law who didn't want their daughters-in-law or daughters to go to the Anganwadi, but wanted to have them in control in their houses, or husbands were a little hesitant, we find that the community led by the Panchayat members were tremendously effective in convincing people to come forward for this program. And most importantly, programs of this kind are not just programs aimed at addressing, say, malnutrition, they are programs that look at malnutrition, because malnutrition is a manifestation of other problems, problems to do with the child sex ratio with gender based violence, with discrimination, with labor force participation, with the fact that women have not been able to come out from the first level of self-help groups into setting up micro enterprises of their own and the entire effort at the bunch of things that we call women's empowerment.

So a better future. This picture actually is a woman who is a street vendor who we supported [inaudible 00:20:07] program. And she told us that she was doing this because she wanted her daughter not having to do this. So in a sense, as a policymaker who developed this program, [inaudible 00:20:26], with the help of an entire team of experts, and field workers, and so on, my biggest realization was that the program could succeed only because the Panchayats were ready to take it forward. The Panchayats took it forward, owned it, and innovated with it. And they just pretty much ran with it, which was so exciting. And that's why when I got posted in my next role, from woman and child development... I hope I'm doing okay on time, Apurva?

Apurva Bamezai:

Yeah.

Uma Mahadevan:

... to Panchayati Raj, it was very, very exciting for me. It was a learning experience from the beginning, but very, very exciting for me now to think of what I could do in Panchayat Raj and how I could work with the Panchayats to strengthen Karnataka's Panchayati Raj system.

At this point, I'd just like to tell a little story about... In 1998, when I was director of mass education in Karnataka, we were running... In those days, we had this thing called the Total Literacy program. And once the Total Literacy program ran its course across all the districts, I as director, mass education, my team came up with a state level mass literacy program, which we wanted to do. Because we had, by then, realized that a country with a low to medium literacy rate requires several waves of a literacy campaign in order to achieve better literacy rates and better impact on the ground.

When our team was rolling out this program in 1998, I still remember, we were pleased with ourselves, we had taken up a campaign across three, three and a half million people between the ages of 15 to 35. It was volunteer-driven. So we were patting ourselves on the back, and I had this ambassador car, I had two drivers. I was very young then and I was full of it. I thought I was really doing something important.

I had two drivers and we drove around to see what the Panchayats were doing, what was happening on the ground with volunteers. I remember going to Kolar, one of the districts in Karnataka, and visiting... These were called literacy centers, [inaudible 00:23:06]. So I visited one of them and found it was great, because there were women sitting there and learning to read after a full day's work, physical labor. And I was extremely naive then. And I really thought this is something fantastic. It is something fantastic, but I was still very naive.

So I came out of there and the local Panchayat president had come there with me. So he said, "Why don't you stay back for a cup of tea." A little reluctant because I wanted to get into my car and go to the next literacy center and visit it. But I said, "Okay, let's have a cup of tea." So over a cup of tea, I still remember, he suddenly asked me, "Can I ask you a question?" This 1998. And he said, "You know, you're doing this, this is a great thing. You're doing it with volunteers, you're doing it at the end of a day. And you have student volunteers, they go to school all day, the women go to work all day. Why don't you think about what Cuba did and shut down the schools and extend the summer holidays and send the teachers and high school students to do this, and do it for three months or four months, and you can cover the entire set of people and you can bring a tremendous jump, say, 5% or 6% or 10% jump in the literacy rate?" I was really taken aback by the boldness and the vision in that question. I still remember. That was my first interaction with the Panchayats of Karnataka.

After that, I started writing to them, and this was still 1998, and we didn't have email in the Panchayats, then. And so I used to write to them in government letters to all the Panchayats across the state. And they used to reply to me. I used to write to them about this literacy program, and they used to reply to me in the letters. I still have some of those and those were remarkable because they replied with a lot of thought, a lot of ideas, suggestions, and they wanted to make contact, they wanted to make contact in the government, in the state level.

I would like to, at this point.... There are many people here who are listening, who are very, very well versed in history of Karnataka's Panchayats and development of these Panchayats. And there's a lot of stuff which has been written about it, which is by people who are experts in this. But, to my mind, I just like to share that in the evolution of Karnataka's decentralization and Panchayats and local government, there are four milestones that I see which are really important, one, of course, is in the 1980s. We should go by the slide.

One, of course is in the 1980s when the Panchayat Raj Act itself, the Mughal Panchayat Raj Act in Karnataka came into being. This was before the 73rd amendment of the Indian Constitution. This was the vision of a very great person, the statesman called [inaudible 00:26:37], who was the minister for rural development. And he was known for two things. He was known for solving the tremendous drought, the water crisis in Karnataka at the time, and he was known for decentralization of a particularly radical and visionary nature. A tremendous moment for Karnataka's decentralization.

One of the things, a lot of people say a lot of things about the '80's Act and praise it for many things. IAS officers, for example, who are votaries of the Act, the few IAS officers who were votaries of the Act, talk about how the these Gram Panchayats had functionality called the chief secretary. So every Zilla Panchayat had a chief secretary and the chief secretary was senior to the deputy commissioner. So that's something that people talk a lot about. But for me, I think the most remarkable thing about this Act was, even at that time, 25% reservation for women back in the 1980s.

The next moment, of course, was 1993, with the 73rd amendment and Karnataka being one of the first states, I think it was the first state, to come up with its own Act, increasing the women's [inaudible 00:27:59]. Many things happened in the '93 amendment, including the addition of an intermediate tier of the Panchayats, but increasing the women's reservation to 33%.

Another watershed moment, in my eyes, is when Karnataka increased women's reservation in 2010 to 50%. And this happened as a result of a process. Today 21 states in India have women's reservation of 50%. They all started with 33%, but today 21 states have women's reservation of 50%. So when we're looking at the story of decentralization, we need to look at it in a very nuanced way. A lot of people say that the decentralization story, other than Kerala and a few states, it hasn't really taken off. But that's a gross simplification, and it's not even correct, in my view. The very fact that 21 states have gone forward to take women's representation to 50% shows that something's happening on the ground, and the need for representation is being acknowledged.

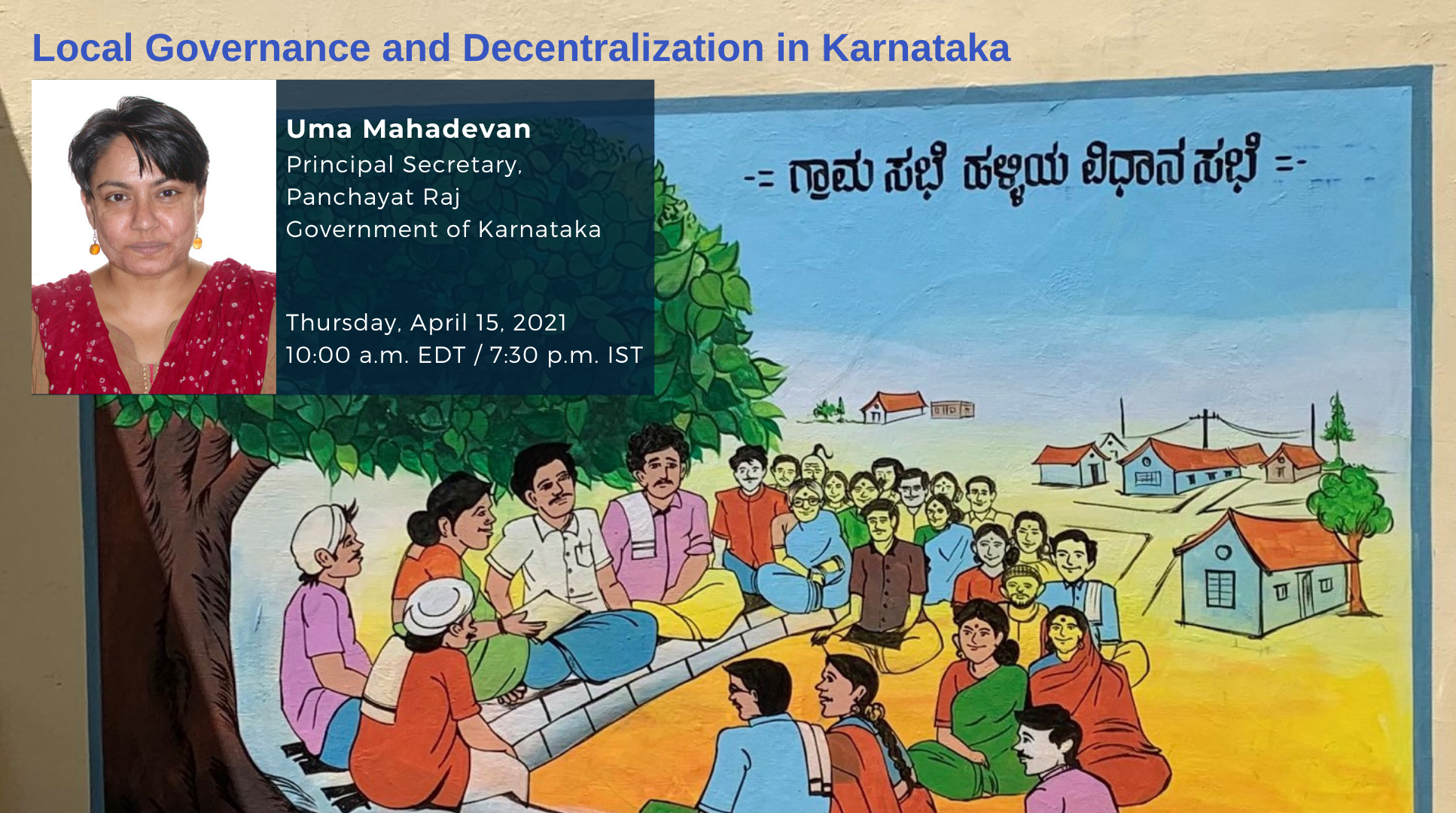

The fourth milestone, I would say... Before I finish with women's representation, this actually is a mural on the wall of one of our training centers. We have training centers in all the [inaudible 00:29:35] of the Karnataka. Aand the training is going on. Even as I speak, we've completed six rounds of training of the newly elected Panchayat members. It's the sixth cohort which has been elected after the '93 amendment, after the 73rd amendment. And we are training 90,000 Panchayat members over 10 weeks, five-day courses in 285 centers with 850 facilitators. It's quite amazing. But the most important thing is that we're doing it in a hybrid mode, non-residential, with expert videos, mentored group activities, and daily online summarizing and clearing of doubts. And touchwood, it's been going on quite impactfully since February 16.

So this mural I saw on one of the walls of the Panchayats training centers, and the very fact that it's there as a mural is a testament to how much it means that women have been achieving this. We actually have slightly more than 50% women in membership now. Also happy to say that we have at least 51 trans men and trans women who have identified because the state transgender policy also was announced in 2018, after which trans men and trans women can self-identify as trans. And so we have one trans woman who is even elected president of a Panchayat in Mysore, possibly the first in India, and we're very proud of her. We're going to have a special training for the trans members very soon at the State Institute of Urban Development.

The fourth important moment I think for Karnataka Panchayats, I think, came last year with COVID. And that's when it really came into them. Until the year 2000 we were really still talking about the old story of, "Funds haven't been transferred, functionaries haven't been transferred, functions haven't been transferred. We've got an incomplete devolution and what do we do?" Maybe the whole promise of decentralization hasn't been met, and maybe we should even just leave it as it is and continue with the parastatals and [inaudible 00:32:15], and so on and so forth. Then suddenly in March 2020, the pandemic happened.

There was this huge vacuum in rural Karnataka, and we set up immediately what are called Gram Panchayat task forces, which became a platform to bring together the elected members, the Panchayat staff themselves, and the frontline staff like the ASHA worker, Anganwadi worker, the teacher, the village accountant, the police official, and even the librarian or the village rehabilitation worker and so on, to immediately get them to fill this vacuum. Because state level officials couldn't reach the Panchayats, the lockdown had been declared, we needed to communicate with the Panchayats to prevent anything untoward happening due to information asymmetry.

I still remember this was about slightly over a year ago and we said, "We can't even do face to face training, we just have to talk to them on YouTube Live and hope that they make in." And we sent out a message on WhatsApp the day before and said that, "Tomorrow we will train the Panchayat ask forces from 11:00 o'clock in the morning, please come and sit in front of your computers." At 10:45 they had joined, they were there and they were sitting in front of their computers waiting for the training session.

So we trained 70,000-80,000 members of the task forces on YouTube Live, it's a one to many but we also got questions coming in on YouTube Live, lots of doubts, lots of classifications which we issued. And the Gram Panchayat task forces took on the responsibility of effective COVID management in rural Karnataka, which meant the following; initially we had only started with dissemination of science-based information about the virus ,because we didn't want misinformation to go in with the superstitions and maybe ignorance and so on, but science based information. So we had the the Panchayats just immediately took it on, we had [inaudible 00:34:43] made of Coronavirus, we had lockdown implemented effectively, we had people communicating about what were the precautions to be followed so that there wasn't a sense of panic.

We had Panchayats going house to house with the ASHA worker and Anganwadi worker in order to do a house to house survey which was done for the first time in Karnataka by the health department and by the Panchayats to identify those who had vulnerabilities, whether they were pregnant or had NCDs, or was stroke victims, or cancer patients or tuberculosis, whatever, or senior citizens, the Panchayat had a list. Panchayats set up a help desk. They took on the work of relief, they took on the work of providing shelter to migrant workers. It was happening faster than I could follow. When I got the time when I'm in my car, I usually post these things into my Twitter account so that there's somewhere I bookmark it for my own reference later.

But Panchayats were passing resolutions saying that nobody should go hungry within the Panchayat limits. They were organizing shelter and meals and even clothes for migrant workers. Most importantly, they were organizing institution quarantines. The Panchayats run institution quarantines, something like 10,000 or 11,000 institution quarantines, managed the quarantines effectively without permitting transmission. They were organizing health screening using pulse oximetry and blood pressure monitors and glucometers. They managed home isolation over time. They started testing first with rapid antigen testing, and then even PCR testing. And now, most recently Panchayats are organizing vaccinations of the eligible population. So this was one of the things that they did.

But I think the most important two contributions apart from effective COVID management was the fact that relief was something that they took far beyond the enabling orders that we passed. We did pass some enabling orders saying that, "If there are migrant women who need sanitary napkins, please go ahead and provide it from your finance commission grants or from your own sources of revenue or whatever." Relief for migrants, that was something that Panchayats took to like fish to water.

There were people coming back from say Maharashtra who had worked in [inaudible 00:37:33] restaurants for years and suddenly thrown out after the lockdown who had come. And so there was a Panchayat I remember, Panchayat in somewhere in [inaudible 00:37:42] where there were families staying inside the government school. The Panchayat gave them cans of paint and brushes and said that, "If you feel you can paint the school, and we'll pay you at MGNREGA wages. Because it's not an MGNREGA approved work, but we'll pay you at the same rate." And then after they painted this, because... And they were interested in painting it because their children would now go to the same school, perhaps. And after they painted this, they got together and started planting a garden in the compound of the school, and late at night with mobile phones, they were registered onto MGNREGA, given a job card, things like that.

So it was quite moving to see the ways in which Panchayats readily came forward to handle the difficulties of their people. Sometimes they pressed private cars into service to work as private ambulances, sometimes they would organize for milk donations because children need the milk, the elderly need milk. Sometimes they would organize mobile health visits on motorbikes to remote areas. So these were really quite remarkable. This I think was a turning point in Karnatakas Panchayats story because the Panchayats all along departments and those... Because nobody likes to decentralize below their level, we know this, but all along those who were opposed to decentralizing to the Panchayats would talk about how the Panchayats don't have capacities and they haven't demonstrated their capacities, they haven't really faced a crisis, but here they were, not only facing the crisis, but effectively managing it, controlling the spread, controlling the problems of relief and also preventing stigmatization of those who were coming back, those who were in quarantine, those who needed to be taken to hospital. So except for the odd isolated case, I think Karnatakas Panchayats really handled the contact tracing, the monitoring of home isolation, the provision of support to patients, COVID patients very well. So that was one of the things. Those are the four milestones I think.

I will just go through a few pictures that I wanted to show you and wind up. The other thing, I did want to talk about how Panchayats are an effective platform for convergence, which is what they did during COVID. They're also a tremendous platform for participation. When do children get to interact with the government? Children get to interact with the Gram Sabha. Children's Grams Sabha get to interact with the Panchayat every day. Even two days ago, there was a child in [inaudible 00:40:51] who went and gave up letter from his school, from all his friends to the Panchayat saying that, "We need a library. And we need a library which is open for longer hours, and so on."

So children's voices. This is something that built into our Panchayat Raj act. And you can see this is a ground summit that I attended in [inaudible 00:41:11]. The children had very strong things to say, the little girl in red at the left talked about how there are 110 children in the school and they have only two classes and there's not enough space to sit. So we immediately [inaudible 00:41:26] that whatever we can do from our side or from the Panchayat we will do, what we can't will take up with other departments. But these are things that... Panchayats need to listen to their children and this is a forum.

I also think that this is a training... I wanted to take you into what we're talking about. So this is a training center. I talked about the training that's going on for 90,000. This is in Kodagu. And what the trainers have actually done is, Karnataka has an activity based learning curriculum called Nali Kali for children, where we have these danglers which are dangling on the ceiling. But what they've done is use the same concept to create danglers with important sections of the Panchayat Raj Act. And create a really tremendously positive energy and a very engaged training center for Panchayat members, newly elected Panchayat members, this is [inaudible 00:42:26]. Every five day training seems to be having an impact because they're coming back and I've now been told that the last set of trainings of last month has resulted in 40 new libraries being set up by the Panchayats with public parks and the Mahatma Gandhi NREGA, and many other plans that they have. So this is one of their training centers.

This is a newly elected Panchayat member being invited to the training, we thought it was very important that they take their training seriously because we believe that they need to learn certain skills of how to run their Panchayat. Then once we empower them with those skills, they're able to effectively perform their duties.

This is a library that I visited a couple of weeks back in Chikmagalur. A new library set up by the Gram Panchayat. It's a Panchayat with a revenue of around six lakhs, very small little budget, but it's set up this library. And when I went in there, I found a group of children reading comics, storybooks, textbook, a book about science, and they had a dictionary right in front of them. So that was very encouraging and we've also been asking the Panchayats to include accessibility features. So there's a draft and there's also a little bit [inaudible 00:43:55], you can see the widget, there's a widget inside over there in the library. The next plan is to take up through MGNREGA to create a public park so that they have an outside reading areas. I guess that's the screen.

But the last couple of things that I wanted to say was, I addressed a group yesterday about bringing government and governance closer to the people. And I was happy to listen to Kerala's celebrations last week of the 25th year of the decentralized planning. And one of the experts, the former chief secretary... One of the world's experts on decentralization in developing countries, [inaudible 00:44:46], spoke about how, as against the model of rolling back the state, which say the World Bank used to talk about, Kerala has shown how you're able to roll forward the state to the door step.

I think that's really what I was also talking about when I emphasized that it's the Panchayat which can really deal with the problem of exclusion. Inclusion errors, your [inaudible 00:45:14] enough ways to at least try and address by using technology and deduplication software and all kinds of things, but exclusion of the poorest is something that only the Panchayat is, if at all, going to be able to do, convergence as well. And I mentioned yesterday that people were talking about how we need to take governance to the last mile, and I said that maybe what we need to do is really talk about... It's not just semantics, but we need to really talk about initiating governance from the Panchayat and talk about it as the first mile. Because that's the principle of subsidiarity as well, and then maybe we will find our way through this conundrum of where we take decentralization forward a lot better. So I'll stop here, Apurva, and [inaudible 00:46:12].

Apurva Bamezai:

Yeah, yeah no, we in fact have a number of questions lined up already so thank you for that fantastic talk. I will actually start calling on people. I'll take maybe two questions and you can tell us if you want to take more as we go. So, Bhumi and then Jusmeet, could you just unmute yourself one by one?

Bhumi:

Hi, thank you so much for this presentation, I learned a lot. So my question was, I was really impressed by all of the changes you enacted in the Anganwadi that you spoke about earlier. I was wondering if you could talk a bit more about the changes you had to make to the incentive structure of the Anganwadi workers? So if the changes you made coincided with their motivation, and ability to perform the new tasks.

Apurva Bamezai:

Jusmeet, do you also want to speak up?

Jusmeet Sihra:

Yes. Hi, thank you very much Uma for this wonderful talk. I have a question around caste discrimination, so you mentioned a bit about that. But could you please talk a bit more about how you deal with more resistant cases of caste discrimination on Anganwadis. And I asked this because I was doing ethnography in three scheduled caste slumps ghettos in Ajmer in Rajasthan, and I observed very strong caste discrimination practices. So for instance, in one case, it was Khori neighborhood and the Valmiki, Balmiki kids were not welcomed inside. In another case, it was a [inaudible 00:47:51] ghetto and the in charge was a Valmiki, Balmiki woman, and she was not allowed to touch anything. So how do you tackle with such structural issues in your work? Thank you.

Apurva Bamezai:

Respond now and... Okay.

Uma Mahadevan:

Yeah. Thanks, both are great questions and important points. Bhumi you wanted to know about incentive structures for Anganwadi workers, very, very important. I think the first crisis I had to actually face was a strike by Anganwadi workers. They are honorary workers, they're on an honorarium. ICDS, as you may know, is a central government program, with the central government paying a share and the state's paying a share.I think there are close to 1.4 million Anganwadis across the country, it's not easy to bring changes to the incentive structure within that program. So many states actually top up from their own resources, the honorarium that's paid to the Anganwadi workers and the helpers. This is also what Karnataka was doing. And Karnataka since 2013 had been steadily increasing the honorarium paid to both workers and helpers every year.

However, what we realized was that increasing the honorarium was only one of the measures that were effective... And you can only increase up to a point based on the available resources. But there were other things that we could do, which were perhaps not so expensive to the state, but would go a long way in reducing the sense of insecurity that frontline workers had. One of the things we did was to bring in an online system of recruitment so that recruitment applications followed the principle of seniority and were transparent, rather than applications suddenly disappearing when they were put in and so on. So that was one of the things. And bringing an element of transparency to it.

The second thing was that we... Anganwadi workers and helpers have a fairly large gap in the honorarium that's paid to the one and to the other. But it's not so easy to reduce that gap, because there is a cost to it. But what we did was that we treated them the same as far as medical benefit was concerned. We had 20,000 for the worker and 10,000 for the helper but we made it 50,000 for critical illness for six months [inaudible 00:50:45], and we said it's 50,000 for both, whether it's for the work or the helper, so those kinds of things. And then we brought in the concept of an appointment for some elements that gave them insecurity. If they've died in service, if there was a death in service, then out-of-pocket expenses for their family, and also if they had an eligible daughter or daughter-in-law, because it's a job for women, it's a feminine work force,. If they had an eligible daughter or daughter-in-law, they would get priority in those appointments.

So these measures were brought in after discussing with the unions and with representatives of the Anganwadi workers, and these not only help to reduce their insecurity, but also help to open up a level of communication with them. We also try to understand what were the things that cause this huge sense of tragedy in their work. So one of the things we did was to bring a brilliant a specially designed technological platform, an application on a smartphone. And we said that the first thing that you need to do is to reduce the tragedy of the [inaudible 00:52:03], let the phone do everything that a phone can do so that the human can do everything that only a human can do; the caregiving, to play with the children, teaching, looking after them, and so on. So 11 registers. We've heard a lot about these 11 registers, 18 registers, 16, whatever, but bring all those registers into one application so that you're not typing 15 times into the phone the same name, you're not tracking, you're managing, you're beginning to feel like a professional.

It's not about the amount of honorarium that you get, but if you're treated as a professional, and if you're given a training, and you're given a phone, and you're given an application, and you're given the sense that your time is valuable, then you begin to feel less of a sense of insecurity, and you begin to be able to do better at work as well. Those were some of the things that we did. We didn't do three or four things, we did 8 or 10 things. It's been a while now, so I don't remember all of it, but we got into the details of their working conditions.

I think that's something that really helps in dealing with frontline workers, because certainly there are problems, but equally there are problems of resources and constraints and therefore, it's important to get into the details of their working conditions to see what are the ones that you can solve, at least even if you can't solve all 15 of them, you can solve maybe seven or eight and reduce that huge sense of the weight of all the stress and the care that weighs on them. So that was one of the things.

The second question about caste discrimination. Yeah, really, really important question and a really good question. I have seen this in different forms in different parts of the state. There's caste discrimination and there are other kinds of discrimination as well. However, I would still say that a good Anganwadi, well functioning Anganwadi worker, helper, supervisor, a Panchayat member, whoever champions this and prized to work with it can bring about a sense of community.

For example, one of the things that we found was initially when we brought the... I spoke a little bit about it, when we brought the hot meal program, we found that some of the mothers in some of the places were a little hesitant to come to the Anganwadi, because they felt that it was... In India, we have this phrase in for a day, it was not cool for them to come to the Anganwadi because, "It's okay for the children to go, but I have enough resources to make my own food, I don't need to come to the Anganwadi for food." But then we said this is not about coming to the Anganwadi for food, this is about coming to the Anganwadi for proper care, to ensure that what you eat is balanced and that you also get the other inputs in terms of the health interventions, the counseling, the talking to your friends, the spending time all of that. So that was one of the things.

The other thing was, sometimes we would see women not coming because of, as I said, past. We discussed it openly. We discussed it openly and said that when your children are coming in there, and your children are eating eggs... We started eggs and we found that children of parents who may or may not have been eating eggs, the children were eating and the parents will say, "Yeah, that's fine, if my child wants to, let my child eat." The children were aware of getting through to the parents, the children were a way of getting through their mothers.

Anganwadi are really at the heart of community, and well-functioning Anganwadi can, over a period of time, bring a certain change in the ways in which parents interact, especially when the mothers start coming to the Anganwadi. Because I already told you about how I have personally seen women who sit very, very peculiarly facing the wall and eating because of the evil eye [inaudible 00:56:41], and within a week [inaudible 00:56:43] that they start facing each other and sitting and talking to each other. And then I start watching them. And pictures would come in, pictures were coming in. It was a crazy time, because... I mean, thank God for WhatsApp because pictures were coming in every day, several times a day, too fast for us to even make sense of it sometimes. But we would see them changing perceptively in the way they were interacting with each other. We'd see women talking to each other, we'd women walking out together.

Initially, there were questions like, "What if women can't come all at the same time?" So then we'd say, "Okay, they can come at different times just leave the food on the kitchen counter so that they can come and serve themselves." You could see that over two or three months, they'd start coming together, they start talking to each other and walking down together and coming back together. So we will see these things changing.

Again, all of this kind of change, I've never personally seen what I used to see many, many years ago of different kinds of water being provided for different children or different mothers and so on. I haven't seen that happening now. And I'd say that Karnataka certainly is a different space as far as that very sharp and very visible caste discrimination is concerned.

Having said that, I wouldn't say that it's not bad, it's certainly... Caste feelings run deep, they exist, but I have seen great pleasure, and it's been an honor to see in Anganwadis, open Anganwadis [inaudible 00:58:20]. There'll be [inaudible 00:58:22] women sitting with Dalit women and their children on the other side and some people are eating eggs and some people are eating vegetables, or green gram and they're sitting together and the eating and they're talking to each other. And that change has happened because it's a cramped Anganwadi. Maybe if it was a very large, spacious Anganwadi, they all have different corners [inaudible 00:58:41]. But because it's a cramped Anganwadi, they have to sit in a line and the children have to be on the other side and then this was happening. So some of these things I think can happen by getting people together in places like this. And the [inaudible 00:58:57] meal had begun to become one of those platforms. I am sorry, that's partial answer but I really wouldn't be able to say more than that at this point.

Apurva Bamezai:

Thank you so much, and I promised Ahmed would be the last question and then we have to wrap up.

Ahmed:

Thanks. I'll be very quick. So thank you for the presentation. My question is on the program on nutrition. So as malnutrition is very is a multifaceted issue and it requires coordination between different sectors. So one question is, how did you manage that because there's often turf war between these sectors? And secondly, I wanted to ask about political commitment behind some of these sectoral issues, and whether that was the case in Karnataka or not, because that could also explain the budget and the forces coming together to address this issue. So, I just wanted to get your sense on that.

Uma Mahadevan:

Yeah, thanks for that. Karnataka at the point where we came in on malnutrition free Karnataka already had a program of Hunger Free Karnataka, so that vision was already there. So we were only taking it forward by many steps and saying that now we need to work on malnutrition free Karnataka, that was the first thing that we did. The second thing was that, like you said, it required multi-sectoral coordination. There was a slide that I showed, I didn't dwell on it but we set up several platforms, several committees at the levels of the chief secretary and the development commissioner and so on for monitoring the ministers level. The minister herself spoke to 1000 supervisors in an all day meeting in South Karnataka, and then we traveled to Raichur, where we again spoke to 1001 Anganwadi supervisors in an all day meeting in North Karnatika. So these meetings were attended by district officials, by people who would provide water.

We understood malnutrition as a weighty problem, as something that was complex, as something that needed solutions of water, of electricity, of toilets, of providing additional food, better quality of food, growing nutrition gardens, converging MGNREGA, and so on and so forth. So, we posed that as well as a problem to districts and we built in that flexibility and that amount of decentralization for districts to own their solution. So many districts decided to focus on, say, nutrition gardens, so there would be nutrition gardens with Moringa plants and gooseberry plants and things like that coming in and that would be part of the MGNREGA budget. There will be other districts where there'd be a focus on drinking water. Provision of drinking water one way or the other, either from the Panchayat or from the [inaudible 01:10:14] plant or for the Anganwadi to have this. So many, many things were addressed in different ways and we encouraged people to try all possible ways, because we knew that it required all of it and no one thing could do it, maybe not even 10 things to do it, but we needed everybody pitching in with whatever they could at those points in time.

Apurva Bamezai:

Thank you so much. Thanks for everyone who stayed, though, beyond 11. Join me in thanking Ms. Mahadevan for joining us today in this great talk addressing a very interesting and important topic. We hope that we can host you in-person the next time. I couldn't take a lot of questions, but thank you so much for your participation. Just a quick note, next week at 12:00 PM, Eastern and 9:30 PM Indian time, we're hosting Sanjeev Routray from the Department of Sociology University of British Columbia on the topic of numerical citizenship struggles in contemporary day. Yeah, thank you so much everyone and see you next week.

Uma Mahadevan:

Thank you. It's been a pleasure.