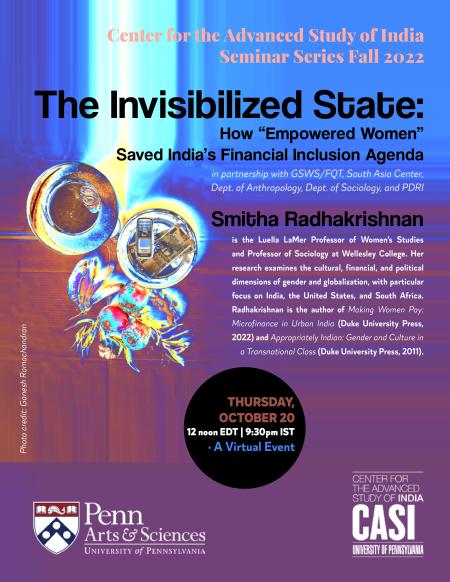

The Invisibilized State: How "Empowered Women" Saved India's Financial Inclusion Agenda

(English captions & Hindi subtitles available)

About the Seminar:

In recent decades, in line with UN millennial goals oriented toward “financial inclusion,” the Indian government, together with the private and charitable sectors, has greatly expanded access to basic financial services. But these efforts are only the most recent of a long history of state-led efforts, dating back to the colonial era, of state-led attempts to provide fair financing to India's masses. In all these earlier efforts, gendered constructions shaped banking policies' triumphs and failures. Triangulating data from interviews, historiographies of banking and recent regulatory debates around microfinance, this seminar constructs a history of gendered finance in India, from colonial agricultural policies to microfinance. Radhakrishnan argues that the current dominance of private financial companies in the space of "financial inclusion" targets women borrowers through empowerment discourses, but ultimately further constrains their opportunities for class mobility. These moves became possible as the state slowly abdicated its role in overseeing private financial companies. Radhakrishnan proposes a tentative framework for understanding India's gendered financial ecosystem at multiple scales.

About the Speaker:  Smitha Radhakrishnan is the Luella LaMer Professor of Women’s Studies and Professor of Sociology at Wellesley College. Her research examines the cultural, financial, and political dimensions of gender and globalization, with particular focus on India, the United States, and South Africa. Radhakrishnan is the author of Making Women Pay: Microfinance in Urban India (Duke University Press, 2022) and Appropriately Indian: Gender and Culture in a Transnational Class (Duke University Press, 2011). She is also the co-author (with Gowri Vijayakumar) of Sociology of South Asia: Postcolonial Legacies, Global Imaginaries (Pagrave, 2022). She received her Ph.D in Sociology from University of California, Berkeley.

Smitha Radhakrishnan is the Luella LaMer Professor of Women’s Studies and Professor of Sociology at Wellesley College. Her research examines the cultural, financial, and political dimensions of gender and globalization, with particular focus on India, the United States, and South Africa. Radhakrishnan is the author of Making Women Pay: Microfinance in Urban India (Duke University Press, 2022) and Appropriately Indian: Gender and Culture in a Transnational Class (Duke University Press, 2011). She is also the co-author (with Gowri Vijayakumar) of Sociology of South Asia: Postcolonial Legacies, Global Imaginaries (Pagrave, 2022). She received her Ph.D in Sociology from University of California, Berkeley.

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Amrita Kurian:

Hello, everyone. Welcome back to the CASI Fall Seminar series. My name is Amrita. Sarath, Tariq, and I co-organized this seminar series, I will be your host for today. Before we commence the talk, a plugging for next week's hybrid event with Rukmini S, who's an independent data journalist from Chennai and a visiting scholar at CASI. She'll be talking to us about data and democracy deficits in India. You can find the details of the event on the CASI website. A word about logistics. The speaker will talk for 30 to 35 minutes, which will be followed by Q&A. If you have a question, please drop your question or intimate me using the chat function. Today's event is co-sponsored by the program in Gender, Sexuality and Women's Studies and the Center for Feminist, Queer and Transgender Studies, along with South Asia Center, Penn Development Research Initiative and the Sociology and Anthropology Department.

Lastly, it gives me great pleasure to introduce today's speaker, Smitha Radhakrishnan, to you. Smitha Radhakrishnan is the Luella LaMer Professor of Women's Studies and Professor of Sociology at Wellesley College. Her research examines the cultural, financial and political dimensions of gender and globalization with particular focus on India, the United States and South Africa. She's the author of Appropriately Indian: Gender and Culture in a Transnational Class published by Duke University Press in 2011. She has co-authored a book with Gowri Vijayakumar called Sociology of South Asia: Post-Colonial Legacies Global Imaginaries, published by Palgrave in 2022. Her talk today draws from her most recent book, Making Women Pay: Microfinance in Urban India, published by Duke University Press in 2022. She'll also be talking to us about the new directions she plans to take alongside this project. Her talk is entitled The Invisibilized State: How "Empowered Women" Saved India's Financial Inclusion Agenda. Welcome, Smitha, and I look forward to your talk.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

Thank you so much. It's really wonderful to be here and thank you, Amrita, for the invitation, and I'm excited to hear what all of you think about this. This is actually from one particular chapter in the book. It was the most difficult chapter for me to write. It was the one that took the longest and was the most laborious to actually assemble the ideas for. But perhaps surprisingly, the hard work or unsurprisingly, I don't know, it ended up being the thing which I found to be most insightful for the project as a whole in terms of where I wanted to go later in terms of thinking comparatively about a next project. I'm going to lay out the findings and the key things that I want to say about this chapter, why I think they're significant and how this particular chapter and its methodology and the hidden financial architecture that it revealed for me is paving the way to my next project.

All right. This is my book that came out Making Women Pay. As it turns out, Duke is having a 50% off sale, so if this is something that you haven't had a chance to get ahold of, please go check it out. It is on sale through the end of December at a discount price. The book is mostly ethnographic, but the chapter that I'm going to present to you today is based on historical analysis of reserve bank documents and policy history. I was telling Amrita, it's a little nerdy for me. I'm already nerdy, but it's very extreme, but I hope that people find points of engagement for it. All right. When I started out, one of the motivations for this project, perhaps the key motivation for this project was looking at the rapid expansion of commercial debt in especially urban India, but also in rural in India.

When I got into the context, the thing which became very apparent is it's not just that there were lots of companies, but that rural and urban India is saturated in gender debt. They were talking about urban and rural communities in India that have now come to the point that they rely on debt that targets women in order to make ends meet. This is true for both working class and poor women, poor families, and this has actually been understudied. It seems like there is a burgeoning and two big literature on microfinance, but in fact, the details of how the sector actually works, what the policies are that drive it, why it works in the way that it does, there's actually very little scholarship on it. It's one of those things where it appears that it's abundant, but the way that it's framed misleads us into thinking about what's actually there.

In India, what am I talking about when I say that there's an abundance of debt? Well, first, there's self-help group debt. This is debt that came out of national policies from NABARD, the National Agricultural and Rural Development Bank, and that organizes women into small groups and links them to an actual bank. An actual bank, when I say that, I'm talking about a mainstream state-supported bank. These are like Punjab National Bank, like banks that are state-led and state-supported.

Now, the newer kind of debt that is swimming around in both rural and urban India is debt from microfinance institutions or what I'll refer to for the rest of the talk as MFIs. These are commercial institutions. They have a for-profit, profit-oriented commercial firms. They bring debt to the doorsteps of women, and they're not going through an intermediary to get that linkage to the bank, the bank is coming directly to them. Now, what is perhaps surprising is that both of these kinds of debt are state-sanctioned. When you talk to people who are in the microfinance sector, they believe that they are doing something entirely private that has nothing to do with the state. But when you look more closely at the context in which MFIs came to be and how they expanded, the state is actually very heavily involved both in funding the MFI sector and regulating it. I'm going to explain why these two forms of debt are so enmeshed with one another and why they point us to looking at financial histories and financial geographies of inequality in India.

All right. In case this area is new to you, these are just a few of the commercial microfinance firms that have cropped up in India in the last two decades. I did do research in some of these, which I have used pseudonyms for in the actual book, but not all of them, but this gives you a sense that there are many, many firms that are competing. In a big city like Chennai or Bangalore, you might have four or five of these companies competing for the very same clients in an urban neighborhood. When I say saturated, I really mean that there are a multiplicity of corporate as well as government actors that are trying to give loans to the same women. These are all the commercial organizations. There are state-led organizations that are in there as well.

One of the key questions that I started out with this research is one that seems quite obvious but is actually not examined very often. Why is it that state-sanctioned financial services target women? Why do they target women and not men? If you look at Latin America, microfinance institutions target men and women equally. If you look at Southeast Asia, you see that over time they started targeting women, but over time became more gender equitable. Why is it that in India is it still 96% of microfinance loans that go to women? What I found is that when you actually talk to people in the industry, there is an unquestioned assumption that small loans should go to women and not to men. People don't actually think that that's something you can ask a question about. It's like an obvious, "Well, of course we can't lend to men," which is of course where I started getting curious about. "Well, there must be a reason for that," but I have to uncover that.

My question was really about where this prevailing orthodoxy comes from. It is pervasive. When you talk to people who are within banks even at the very upper levels, the idea of loaning to men, they just say, "Oh, but they'll never pay back. We can't loan to men. It's been tried and it's failed. We don't loan to men." I wanted to look into this a little bit more. Now, what I found is that if we look at the policy histories, there is a key convergence. There is a convergence between programs oriented towards women's empowerment and completely separate programs oriented towards financial inclusion. What I hope to convince you of partly, and I'll give you a little bit more information about what I want to convince you of, is that women's empowerment, that focus, it became very recently the focus of financial inclusion efforts and that saved national efforts to further financial inclusion, which had been stalled or ineffective for over a century.

What I'm arguing is that we can't think about microfinance as its own special product, but rather part and parcel of a much broader and larger history to include India's masses in the formal financial system. The focus on gender debt, however, displaced other programs to improve women's well-being and access to vital resources and services, so there were many other ways in which, not just NABARD, but many other movements and government policies sought to bring resources and services to women around a radical women's empowerment agenda, but the success of these financially oriented institutions or the proliferation of them actually ended up displacing some of those programs, so that now both women's empowerment and financial inclusion have become the same thing.

What I hope to argue or lay out for you today is that the current state of this gendered financial ecosystem that we have in India today, that it comes from a multi-layered colonial and post-colonial history in which successive governments have tried to provide banking and financial services to marginalized groups and most recently to women in particular. What that has meant for women is that their position has shifted, where previously women were completely excluded from financial services and products, they are now the object of those products, and they're the subject, I guess, because they're being extracted from, and now they are the subjects of extraction.

The policy changes that have occurred since the liberalization of the banking sector really in the 90s have enmeshed the nationalized banking system with the interest of private financial companies such that those two now cannot be viewed as separate, and that's what I'm hoping to convince you of. What that has meant in practical terms, if we're talking about a concern with working class women in their livelihoods, is a significant transfer of moral and political imperative to include women in the financial system to commercial financial companies. It's now commercial firms who are doing that work and not the government. We can talk about this as outsourcing or we can talk about it as devolving that responsibility or I think there's many different words that you can use, but it's no longer, they pretty much just handed it over onto the shoulders of commercial firms. This transfer has thus produced that saturation of gender debt that requires the extraction of value, not just financial value, but also symbolic value from marginalized groups of women. That's what I'm hoping to convince you of.

Now, why does this matter? When we theorize financialization and the expansion of the financial system, we actually need to recognize how the actions of private firms and state policies work together, and that the state itself is not a unified actor. For example, what NABARD does in the area of financial inclusion and gendered empowerment is not necessarily working in concert with what the RBI or the Reserve Bank of India does, and that those things can actually unwittingly produce outcomes that deepen or entrench women's marginalization further.

It also shows how implicit or explicit gender politics of financial policies really matter for the understanding of our financial system. When we think about financial policy, it's ungendered, it is non-specific, but in fact, these have real geographic implications in terms of the geographies of inequality, but also particular impacts on women themselves. All right. To convince you of this, I'm going to go through four key time periods. I'm going to try to spend a little bit more time on the more recent ones, but I'm happy to answer questions about the earlier ones, just in order to be able to focus our presentation a little bit more and let you know the new direction that I'm going on that I would like to get your feedback on. All right. These are the four time periods, British experiments with social banking, post-colonial community banking and its decline, and then liberalization and the new regulated MFI sector that emerges in the last 10 years or so.

All right. The first moment has to do with British experiments in social banking. I'm not going to go into too much depth here except to say that the British were extremely disturbed by the indebtedness of the peasantry way back in the 19th century. They tried to do lots of things to create cooperative banks. They did it very much in tandem like many other institutions that the British created. They were creating them in India at the same time that they were creating them in Britain. You see a huge growth proliferation of cooperative banking in rural areas under the British, and it created the world's largest cooperative banking system. Now, what happened though is that this didn't really include as many people as one would think. At the same time, you had caste-based banks that were operating within caste communities, but these were also very exclusive.

Those British banks really didn't produce, okay, I'm going to say this actually the second point first, it didn't necessarily produce relationships of trust. These banks were poorly managed. They really targeted British who were in India, and the most privileged sections, the majority remained in debt traps. More importantly, women were not targeted as a vulnerable group within these policies. They were assumed to be a part of peasant families, and there weren't really any explicit policies that bothered about women needing financial services. However, what it did do is it set up this stratified banking system that we still have today where the most privilege in society have access to financial services and those who are more marginalized do not have the kinds of relationships that are required to actually gain access to those services.

Jump ahead to independence. What you see is the post-independence government being extremely concerned about this issue and saying, "Okay, the British didn't get it right, but we are going to get it right." You see an unprecedented level of outreach in rural areas towards after independence. Yet, by 1954, really only 9% of peasants in rural areas are using banking services. Then, there's another big push in 1969, all the banks are nationalized, and that sets in motion huge changes to expand access in rural areas, including very strict licensing requirements.

These licensing requirements said that, "All right, if you open one bank or one branch in an urban area, you have to open four in a rural area," in order to be able to make sure that that access is fair. This was very limiting for bank expansion, but this was the way that things rolled out. The other thing that happens during this period, which I'll talk about in more detail later, is the creation of a priority lending sector. The national government sets up a set of regulations, it's the reserve bank actually that says, "Okay, mainstream banks, you need to reserve about 40% of your debt for those priority sectors or those marginalized sectors who have not been allowed access to this finance in the past." That regulation ends up getting created, perhaps unsurprisingly, no bank ever meets this criteria for the next 30, 40 years.

But what it did create was a large culture of mass disbursement that targeted men. During this period, you have loan mailers, where banks are going and basically handing loans out to men, and these are not necessarily rural men who understand what is required in order to be able to take this loan, don't necessarily understand the requirements, et cetera. What ended up happening is most of those loans that were handed out were never repaid, and it creates a massive shortfall that eventually all the banks write off. Basically, a huge effort. Nothing really comes out of it, and during this entire period, women are largely excluded.

What are some of the outcomes of this? It creates a culture of unreliable rural men, the perception that rural men cannot be trusted with loans. What you do see importantly, however, if we care about vulnerability in marginalized areas is that in Behi, in certain regions which had been really targeted for expansion, you do see some reduction in vulnerability and this has been pretty well documented that when those services were provided and available, hunger levels decline, people are able to hang onto their land for longer, there's less land dispossession. There's some important things that happen where that suggest that these worked to some extent. Then, it leaves this priority sector legacy that then becomes an instrument that's used in the period after liberalization and I'll talk about that in a moment.

What happens now in moment three? This is really, we're getting towards the 90s, I'm running through this here. You see a pivot to gendered extraction. First big thing that happens in the early 2000s, the World Bank, after Grameen and after having all this evidence about microfinance working in lots of other parts of the world, it provides $110 million loan. Doesn't seem like a lot, but it's just given to Andrha Pradesh, which has done some innovative things around this. It says, "We're going to support you in the rollout of self-help group based loans." These are the government flavor loans that go and link them to formal banks.

Now, by 2006, 2.2 million households are organized into over 170,000 self-help groups. Radical change in a very short period of time. When I was on the ground talking to people who were involved with this, they say it was like a flash. One minute nobody knew what this meant, taking a group loan, and within two minutes, it felt like everyone was doing it. Now, the Andhra Pradesh government follows up with this Indira Kramthi program, which by 2010 establishes another 1 million groups in Andhra Pradesh. Andhra Pradesh becomes the epicenter of the microfinance revolution, if you can call it that in India.

Now, what's happening in parallel here? They're not doing this in a vacuum. By 2007 to 2010, a bunch of NGOs which said, "You know what? These self-help groups, they're kind of limited. Let's try to find a different way to deliver these loans to women." They start becoming financialized. By 2010, they are attracting hundreds of millions of dollars in foreign equity ballooning their portfolios to $2 billion by 2010. This has become a completely different space by this time, and it ends up becoming its own asset class in India. These are still unregulated called non-banking financial institutions. NBFIs is what they're called for and they're still called that actually, but now there's some other classes, but I won't get into that.

What are the outcomes of this time period? Well, women's self-help groups come to the center of National Financial Inclusion Policy. Now, the only way that Andhra Pradesh government and other state governments around India are thinking about financial inclusion has to do with these self-help groups and they're actually competing with private money on private financial companies to lend out as much money as possible, and now women have become solely responsible for household debt. This was not the case before. What you have, secondly, is a change in 2004, which to my knowledge, no one else has turned this up, but a lot of combing through RBI Circular turned this up. In my interview data, I kept hearing people talk about a change that happened in 2004, 2005, that in one moment the MFIs did not have enough money to lend out and suddenly they had lots of it. I couldn't figure out what happened. Digging, digging, digging. I find that in 2004, the RBI made a small change.

Basically, the change was that regular banks, mainstream state-sanctioned banks, state-owned banks, that they could fulfill their priority sector lender sector lending requirement by giving that money to MFIs. This is where the convergence happens, because at this point, it's a small obscure change to policy. But before this, MFIs had lots of foreign equity, but they couldn't use that to lend it out to clients because India has very strict regulations about the separation of equity capital and debt capital, and they do not allow, under Indian regulations, even though MFIs could take all of those millions of dollars of foreign equity and use it to build branches and upgrade their management, their information systems, and buy new iPads for the people who are going out in the field, they could not actually take that money and lend it to Indian citizens.

But when this change happens, suddenly, instead of going and begging banks for debt capital, those banks are calling them and saying, "Hey, can we give you this money? Because it fulfills our PSL and we hear you guys have a really good deal going on where women actually pay back, so it's a good deal for us, good deal for you." Now that capital can become profitable and the banks give a few billions to MFIs to disperse to women in rural areas.

Microcredit and women's initiatives end up merging and it sets up an overlending situation that balloons and leads to a significant crisis in 2010 that really starts in Andhra Pradesh but shakes up the industry at large, the wild west of ballooning interest rates ends up coming to a crashing halt. I used to know the number at the tip of my tongue and I didn't put it into this presentation, but something like 9 million or 10 million households just do not repay. By some accounts, it is the largest non-repayment in history. Millions of people in Andhra Pradesh just don't pay back their MFI loans and the banks are in a very tricky situation.

Now, in that particular situation, they end up going to the RBI for relief and saying, "Hey, you know what? Actually we're cool with regulation. Please regulate us now." It ends up that the leaders of the top MFIs end up really in conversation with the RBI about what kind of regulation they want, and we can talk about what that interaction looked like, because one has to ask whether the people who need to be regulated should be the ones writing the regulations, but anyway. What ends up happening in moment four, what I'm calling moment four, is the emergence of a regulated MFI sector. This is an important thing.

The MFIs profit-oriented ambitions, it should say ambitions not ambitious, are chastened by the Malegam report. This is Malegam and does this huge committee report at the state and the national level and starts setting up very clear regulations around interest rates, around who can get loans and who can't, a whole bunch of regulations that never existed before. But what I found is that MFIs actually had significant influence over the final shape of those regulations, and it didn't necessarily change what had become the feminization of indebtedness. Microfinance continues to be viewed as an instrument of women's empowerment, and women continue to be the ones who manage debt in their households. The new regulations don't mention women at all. They don't recognize the extent to which this new debt relied upon women's reliability, the fact that they pay back 90% of the time except when in a crisis, their vulnerability and their rootedness to their neighborhoods.

These things are not addressed at all in the report. There's really nothing much about women at all, just that these institutions are doing a great job bringing, extending and doing financial inclusion, and therefore they regulate them, and the industry regroups and carries on as usual. I'm conscious of the time, so let me just say that the outcomes of this is that these small loans become normalized as state policy. It also enriches financial corporations and the profit margins in these firms after a dip ends up going up again. It doesn't change something very fundamental, which is the assumption of a hetero-patriarchal family in which women bring in loans to support the family. If this is something people want to talk about, I can discuss it further. I talked to policy makers and looked at documents that really suggest that, and looked at the everyday practices of MFIs.

Women can't take these loans on their own. They can only do it when the husband provides verification, when there is another source of income that's coming in. Even the people who designed this say, "Well, this is not a feminist policy. It's a livelihoods policy where men and women come together and share resources." It really is making women be people who are in charge of not just managing debt, but managing the finances of the entire household, and the buck really ends up resting with them. Programs that are supporting the enhancement of women's livelihoods, job creation, education, property rights, all of these are sidelined and become not as important as making sure that women are the ones who are managing debt in their lives.

What does this mean for our thinking about the invisibilized state? What I hope that I've been able to convince you is that these efforts, that this is part of a longer history. It's not just something that happened after Grameen Bank, that there have been efforts to reach the peasantry, really, that's that where it originates, that long excluded women. But when they finally turn to women to including women, they did so without a holistic understanding of livelihoods and the labor market, but rather focused only on debt. The reliability of women as borrowers, the fact that women repay right at such a high rate is rooted in gender inequality. But rather than alleviating that gender inequality by enhancing property rights, by enhancing access to the labor market, the expansion of micro-lending actually deepens and reinforces that fundamental structural inequality.

Women become the subject of debt and the object of empowerment. They perform empowerment for everybody else, but they are the ones who must be subject to constantly finding a way to repay. This leads to this other part, which is that gender inequalities are in fact very productive for financial policies that seek to expand the financial systems, and those inequalities have been leveraged and deepened for the smooth functioning of that system rather than alleviated.

All right. That leads me to my new work, which I'm right now calling Patterns of Predatory Inclusion. I'll walk you a little bit through what I'm thinking about here. This is a comparative project where I'm thinking about India, the US, and South Africa. I come to them from new questions that emerge for me from my exploration of Indian microfinance histories.

The first question is a fundamental one and one that lots of people are asking in different contexts, but I come to it from this particular vantage point. Do policies that are intended to put money in the hands of the marginalized actually end up in the hands of those that they intend to? What is clear from looking at the history of microfinance is that billions of dollars, rupees are floating around, but the profit of those actually end up with the captains of financial companies with the companies themselves. The profit of that money is not necessarily resting with the women who take the loans, who are paying huge interest rates and who are in a cycle of debt payment and repayment and not necessarily gaining the benefit of that money. It's flowing both from state as well as from private sources, this question about where does the money go.

There's also more specific questions. How do cash assistance and exploitative debt overlap in the lives of working class women? I'll tell you why I ask that question from some anecdotes that came out of my ethnographic work. This question that we can't just look at debt in a vacuum, we also need to look at it in relation to other kinds of cash that are floating around in women's lives. Secondly, this broader question of how financial inclusion could be reproducing geographies of inequalities along lines of race, caste, and gender.

All right. My new project, I'm looking at these three locations. I'm looking at the US, particularly the South, looking at TANF, which is Temporary Aid to Needy Families and how that overlaps with credit card debt, and I think that they are incredibly parallel and there's a lot to suggest that the history of credit card expansion, the fact that they are available to lots of needy folks now in ways that they weren't 20 or 30 years ago, overlaps with the very poor provision of TANF in the US, and I'll give you a little bit ... this is actually what I've started working on so far with this project.

Now, what's interesting is in South Africa is that this is another context which is quite different. Here you have an extensive, extensive, unlike the US program of grant, entitlement-based grants from old age to pensions of various kinds, disability grants, but you also have a very entrenched exploitative debt system that comes mostly from private companies. There is some new research that does in fact look at how these two overlap, and I'm interested in uncovering the policy histories that made that possible. Then finally, in India, you've got NREGA, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, perhaps the largest cash assistance program in the world, and you have microfinance. My hunch is that these overlap in ways that are pretty significant, although they haven't been looked at before.

Briefly, what I know and I hear is where I would love to hear from folks about your hunch about whether this will pan out or not. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act might be the largest cash assistance program in the world. There's a huge literature about it. I have not yet found, although if someone has, please let me know, any research that looks at how women who receive NREGA support manage debt. What kind of loans do they take out? Do they qualify for them? How are they managing that in the context of larger questions about their livelihoods? Might NREGA policies be further entrenching women's roles as part-time workers and mothers who are responsible for household financial management, which is the rhetoric that's used in MFIs and on the ground to really justify the work that women are doing in managing household debt.

Finally, what's the relationship between financial inclusion policies that are out there and NREGA benefits? Again, how do those converge or diverge in real settings? Why I think that there's some traction here comes from my field work. I did a lot of work in trainings, empowerment, entrepreneurial trainings, financial literacy trainings, et cetera. One of the big challenges that the trainers faced was getting women to come. I did a lot of work in urban areas, but I also did work in these semi-urban areas, which are on the outskirts of towns or just outside them where there's still a lot of agriculture. What I found is that the trainers were always complaining that women were going and doing NREGA work, that they were going and getting their daily wage rather than coming to the trainings, and that they couldn't convince them to come and take a training about entrepreneurial training about how to be oneself most and how to become an entrepreneur or how to get financial literacy, that this was a real source of frustration.

I heard this over and over again in multiple contexts and it suggests to me that the scope of NREGA may be larger than what we think, that it's not just about rural areas, but perhaps some of these semi-urban areas as well, and that there is a very high likelihood that women who are getting NREGA are also managing various kinds of debt, whether it's self-help group debt or whether it is MFI debt or other kinds of predatory lending. There's a whole set of questions that I think deserve further exploration.

Now, what I'm also interested in is that Indian microfinance and its history prompts new questions about the US that scholars in the US are not really asking. Where do funds intended for the marginalized actually go, whether they come from private sources or government sources? Since we know that a very small percentage of the funds for US families experiencing poverty actually go to that number, and I have a lot of other graphs about that, but I didn't want to bring that in because of time. Basically, for every hundred families that are experiencing poverty in the US, only about 20 of them actually get cash assistance, the rest of that money, which is specifically for cash assistance, goes to a host of other programs that have nothing to do with poor families. The question of how are these families getting by? How might access to exploitative credit be shaping their livelihoods, is a question that needs to be asked.

There are also critical questions about gender, race, and geography and how they shape the intersection of debt and welfare that also need to be asked in the US context. I know to ask them because of what I see in India. In the US South, what you see is much lower levels of the allocated funds for TANF actually going to alleviate poverty than in states where there are lower black populations. When there are greater black populations, less money actually goes to those families. When there are lower black populations then more actually goes out in the form of cash assistance. There are these really interesting and troubling ways in which patterns of cash assistance deepen inequality and that black women are actually being expelled from the limited safety net that exists.

These are questions that US scholars are not asking because policy conversations about credit and debt are very isolated from policy conversations about welfare, reproductive rights and livelihoods. There's something about the way that these come together in India that, for me, really directs me to look at those questions in the US in ways that US-based scholars are not looking at it. Amrita, I think maybe I can wrap up here. I can talk a little bit about the US. I have a little bit about Mississippi, where welfare funds go and stuff. Maybe I can stop here and if folks are interested, I can say a little bit more about that, but I feel I got a chance to give you my ideas about where I stand on that. Thank you for your time and I look forward to your comments.

Amrita Kurian:

Thank you so much, Smitha. I'm very excited about your new project.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

Thank you.

Amrita Kurian:

We are open for Q&A. If you have a question, please drop it in the chat. While you're thinking about your questions, I have a couple of questions.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

Great.

Amrita Kurian:

I'm very keen on this idea of, there's something that you were talking about the state in India, which goes in contradistinction to the general idea of liberalized India, which is that it takes on a larger regulatory function while diluting its responsibility for women's empowerment as well as divesting itself. It's the responsibility of any sort of collateral or overheads or personal charges and moving that onto private companies. Tell us a bit more about what do you think that makes the state ... What is the state in liberalized India? Secondly, I'm very keen to know ... you told about how multiple MFIs target the same group. They're over-targeted and people tend to take multiple debts out. Yet, some groups still get left out because they can't show their credit worthiness. Being too much in debt as opposed to not having any cash, how does that sort of change exclusive ... or does that change something about social dynamics? Not just of women, but in other forms as well? I do have lots of questions about women in the US but I'll wait for somebody else.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

Okay. Should I get started on those or do you want to collect a few?

Amrita Kurian:

What would you like to do? Would you like to respond to that?

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

I can start out with some thoughts about that and then maybe if other folks want to chime in. These are great questions, Amrita. I really appreciate them. This question of what is the state in liberalized India? I think it's a big question, and I think looking at these history has definitely changed the way that I think about it. One of the things that I talk about, I didn't get too much into the theoretical framework that I use in the book, but it's there in the chapter. There is some literature that looks at how do we understand a post-colonial state that's also liberalizing. One of the things that we don't look at often enough has to do with the transnational influences. In the case of NABARD, NABARD was very much subject to transnational influences from Grameen, from the international arena about microfinance and about small loans for women way back in the 80s.

They are already laying out these programs and they're already thinking about it in a lot of depth, and they are planning actively about how to roll this out. Now, this isn't the only thing that's going on. There is the Mahila Samiti movement that's underway. There's so many other kinds of movements that are thinking about women's empowerment holistically. NABARD never thought like, "Okay, we're going to be the only game in town on this." But they're crafting these policies very much in response to what's going on in the transnational policy environment around women and development. Now, at that same time, the RBI is concerned with licensing. They're concerned with how are we going to get banks to be. They're trying to figure out, "All right, well," they basically take away all the licensing requirements, so that 1:4 ratio, they take it away to try to encourage private banks to come onto the scene.

They want to offer more financial products really to middle class Indians. They don't want to deregulate the whole thing, but they're thinking about it in very gender neutral ways. They're concerned with the rural urban divide, but they're really trying to get banks to be much more active. They have totally different concerns. It's almost like they're all doing their own things with their own sets of influences. RBI's also influenced by transnational policy conversations, but those are around deregulation and feeling like, "Oh, we're too regulated, but we don't want to get into the wild west either, so how are we going to keep our regulations? How are we going to deregulate from the kind of bureaucratic garage that was there before of red tape and be kind of lean, but at the same time not go too far, that our markets go into a windfall." These are just two different conversations, but they end up converging when MFIs bridge that and then start dealing directly with the RBI for regulation.

That's where I think we've misunderstood microfinance as this market-led intervention targeting women. It's way more than that. It has to do with the history of banking in India. It has to do with all of these different regulations and institutions, and we're missing the forest for the trees when we have two narrow a conceptualization of what actually happened. I think that it's a way that we can look at how disaggregated the state is and the different kinds of influences that are happening at the same time. There isn't that we can't cohesively theorize what this liberalized state looks like. Even just looking at one product leads us in very different directions. I hope that's something that will be helpful or instructive for other scholars to take up.

As far as the debt versus exclusion, I almost feel that's an ethical or a philosophical question. Is it better to be overly exploited or not exploited at all? It's this Marx and Gramsci ... it's a big question, but I do think for those who are completely excluded from these debt circuits ... I have a colleague, Thien Parvez at UMass Amherst, who's been doing work with very poor Muslim communities in Hyderabad who have been targeted in recent years due to religious violence. They would love to have access to MFIs. All they have access to is the most predatory debt there is and that's predatory exclusion. One of the MFIs that I looked at, they have these CSR, corporate social responsibility programs where they go to really, really marginalized families and give them various types of direct support in order that the women can graduate and take a loan from their organization. They actually see that as an accomplishment.

There's predatory inclusion. Exclusion is maybe not even viable. With the predatory inclusion, predation is happening, but they're moving the money around even if they're not moving up. Unfortunately, when I explain this, people take it as like, "Well, you see the MFIs are doing good." It's like, well, but they're doing that in the absence of any social supports. They're basically filling in things that the state ought to be providing. I have a automatic lighting system, so if I stay still for too long goes off. Anyway, that's my preliminary thoughts about that.

Amrita Kurian:

Thank you. Smitha. Okay. Apurva has a question and then after that, Jusmeet has a question. Maybe we can take turns together. Yeah.

Apurva Bamezai:

Thank you, Smitha. This is fantastic. I wanted to clarify whether, are you arguing that in some way the fact that there is so much state-sanctioned gendered debt in India has somehow also been disempowering? I know you're trying to see the overlap between empowerment discourse, but are you going as far as saying it has been disempowering and if yes, in what ways? I want to basically push you to try and see or try and respond to the findings and say some political science literature recently suggesting that membership or SHG membership has actually improved political participation of women, even of pushing them to perhaps enter electoral races and not just be stand-ins for men. Yeah, just a couple of those. Thank you.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

Yeah, so I think both things can be true. As we know, the definition of empowerment is highly contested. There are many different conceptions of what that means. I think that the economic, the political and the community-oriented definitions of empowerment all exist and they're all relevant. Yes, it might be that SHG members, due to the fact that they come out and connect with one another may be more likely to participate politically, doesn't necessarily mean they have any better access to the job market or that they're better able to hang on to property that's in their name or be able to access their inheritance. I don't think anything I'm saying is contradicting what's there. Both can be true. In fact, many of the women that I talk to, they are politically involved in parties.

That's the other thing is that, the folks who are taking these loans, whether it's SHG loans or MFI loans, they are a very heterogeneous group. Within the same community, the same little alleyway in Bangalore, you will have women who are basically party bosses, who are taking loans from MFIs and not using it themselves, but ghost-lending to all these other women who can't afford to get that loan themselves, and they're doing it and they're able to do that because they have tremendous political power in local politics. I don't know. It's empowering them I suppose, but it's disempowering. I think we've come to a point where this word empowerment has become a little bit of smoke in mirrors, and we are not really talking with any clarity. That's why whenever I use it in my book, I put it in quotes because it's become a word that, what are we talking about anyway? Can we talk about women's livelihoods in more nuanced ways?

Sure, they can come together and go ahead and say be more vocal about women who are experiencing domestic violence, for example. Or they can better know how to get their kid a job because they're meeting other women all the time in these groups. What about the women who don't pay back? Who are excluded? That was very hard for me to research because when you go to the meeting, you see who's there, not who's not there. But when you look around, and I saw this, there was a woman on the margins of a one meeting that I went to who was not a part of the group, and people were whispering about her. I went and talked to her and she's like, "Yeah, I wasn't able to take the loan this time, but I'm going to see if I can take it with them next time."

She didn't have a tally, for example. It was just thread. She was living in very, very ... simple as an understatement, very bare accommodations. She had clearly experienced significant financial distress. She had been excluded from those networks where women are gaining empowerment. I think that we need to now be a little bit more nuanced and specific when we're talking about that and just saying that, "Well, some of the SHG, they have access to political power." Fantastic. That's great. That doesn't mean that we're not at a point anymore that we need to say it's good or bad. Are we still in that moment that we need to be talking about impact in such a uni-dimensional way? I think that we can have a more nuanced conversation about it and we must. We need to get beyond this, is the impact good or not?

We're still stuck in this economistic framing. Do their impacts go up? Do they feel more empowered? When you go and ask women like, "Oh, how was that training? Did you feel you benefited?" They'll be like, "Yes, it was nice," because they're incredibly kind and resourceful, and if you come and ask them, they're going to tell you what they think you would like them to say because they would like to be helpful. I think that doesn't mean that we can't advocate for change on their behalf because of the circumstances. They're making the best use of what they have and doing it in an incredibly resourceful way. That doesn't mean that we can't and shouldn't be advocating for a much more holistic understanding of their livelihoods and having that understanding drive our policies rather than a very thin or uni-dimensional understanding of empowerment.

Amrita Kurian:

Jusmeet?

Jusmeet Sihra:

Yeah. Hi! Thank you, Amrita. Thank you very much, Smitha, for this amazing talk. I'm sorry, I apologize. I won't be able to switch on my camera right now.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

No problem.

Jusmeet Sihra:

I was doing some field work in Rajasthan, where I was working in some Dalit neighborhoods, and I noticed this nexus of geography, castes and banking system and debt. It was fascinating because there was no MFI at all. What existed were these very predatory society schemes where you put money and so on and so forth. I was just wondering, well, what's happening with castes and microfinance, both from the point of view of givers, the companies that are giving these loans, but also the takers? Why in some areas you would have these MFIs flourishing and in other areas you would have these predatory exclusive mechanisms that you pointed out? Thank you so much once again.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

No, that's a great observation, Jusmeet. I would love to hear more about that area in Rajasthan that you're talking about. I don't have a very direct answer, I have circumstantial evidence. The data, the official data on self-help group membership as well as MFI membership suggests that a large proportion of these borrowers do come from valid communities. But what the geography of that looks like I think is a much more complicated question and one that I would like to look into more. It's difficult to study, because I think that some of that within the urban neighborhoods that I looked at, I think they are very mixed in caste composition and that there are layers of class and caste complexity and domination that I couldn't untangle when looking at it just from the vantage point of MFIs. I think that there is a bigger story there that is regional and geographic. In urban areas, some of those things get compressed, I think.

Now, about the schemes that you talked about, those are often caste-based, and that's that legacy of that earlier moment where you have, in the south there's CHICK Funds for example. They're generally among a lot of working class folks in India. Financial companies have a really bad reputation. That's something which I don't think has gone away entirely, and it's because there are these very dubious actors that exist and compared to them, MFIs are like angels, because they have clear procedures once they are regulated. After the Malegam thing, they don't behave in a coercive way, and I talk about some of those things in the book. They treat the borrowers like elder sisters. They don't demean them in that way.

I also think there's another question about caste that needs to be looked at, which is how cast functions within MFIs. My hunch, although I only have anecdotal data from my research to support this, is that those who work for MFIs, whom I show in my book actually profit the most because those folks who go in with an entry level job, if they rise up within the MFI, they actually enter the middle class. Of course, these are very small numbers compared to the borrowers. My hunch is that those folks tend to be upper caste and are probably less likely to be valid than the borrowers. That's because the way that folks are recruited, they are recruited within family networks. Nine out of 10 of the people that I interviewed, 90% of them said, "Oh, my brother told me to go and interview for this job. My uncle told me about this." I think that there are these caste networks through which hiring happens, and those are the folks that actually end up doing pretty well.

I did interview a few folks who explicitly identified as Dalit who work for MFIs, who have experienced some upward mobility, and many of them talked about not being able to get into the upper echelons of those organizations, which are very dominated by dominant caste men. I think there is a ceiling there on the basis of caste and some serious barriers within organizations that have not really been studied. I know that was a little bit outside of your question about geography, Jusmeet, but just something that came to mind.

Amrita Kurian:

Thank you, Smitha. Tariq has a question and then Bhumi has a question.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

Great.

Tariq Thachil:

Smitha, I really enjoyed the presentation. Thank you so much. It's an exciting project and I was thinking of a couple of things I found interesting that in case it's helpful to, as you're thinking for the next step. One, I thought it was really interesting how reputation worked, the construction of reputation on both sides. You had both lending institutions having reputations among borrowers as you just said and what goes into that. But also, the reputations of borrowers themselves, so it was interesting. I really like the historical point of how men became bad borrowers, and what was interesting was that women, while I understand the overall fact of higher repayment rates, even post-crisis, maybe they have stickier reputations, there's a gender difference there in terms of staying good borrowers even if there are realities that might cut both ways on both sides.

I'm sure there's a similar story that could be told with caste or occupation, et cetera, but the composition of reputation was something that was really interesting and I think the combination of ethnography and historical work is really well-poised to advance our understanding of. The second thing was building on Apurva's point and actually your response to it, I think it would be, we're at a great moment and your project would be a great place to think about that variation, that heterogeneity of experience, which is so much more interesting, I agree, than a single argument about is this good or is this bad? There are at least two dimensions that I've been thinking about. One is self-help groups are one dimension of that, but you mentioned NREGA cash assistance, so not just debt, but even the giving of benefits.

Now, there's this whole discourse of women as beneficiaries, eLabharthis, it's very politicized, but it's also very present within India. I think it's an interesting moment to move, not just beyond. Maybe this is going too far for this project, but borrowers are only one instantiation of how women are being seen. Women are also currently being seen as very good beneficiaries. They're good at receiving benefits beyond just loans.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

What's the term that you said is being?

Tariq Thachil:

ELabharthi. I'll type it in the chat box, which is just beneficiary in some ways. I think that it might be interesting to think about almost maybe in an interdisciplinary setting, maybe it's not, it's too much for one person to do, but we do have a lot of contradict ... all of this variation about effects that are potentially helpful to women, those that are not, but also how those are unevenly distributed against different kinds of women. I don't think there's been enough effort to aggregate, even in conversation, forget about in a single work across these different kinds of domains and different kinds of methodologies. Anyway, I'm not putting that on you, but I'm just thinking about that as being a potentially important set of conversations that you should definitely be at the heart of. Anyway, [inaudible 00:59:23], thank you.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

Yeah, thank you. What disciplines do you feel people are, or what spaces are people even talking about? I feel like I don't see [inaudible 00:59:30]-

Tariq Thachil:

Self-help groups have become, as Apurva said, a lot of the work on female political participation in political science has really thought about self-help groups because of their pervasiveness. There's been very interesting work on that. But again, it's been, thinking about it in one particular way, I think it would benefit from hearing your work as much as vice versa. Thinking about political ambition as very different from some of the indebtedness or social collateral and the dark side of lending that you were talking about. But I also think there's been some interesting work that's happening in social anthropology that's thinking about what the act of working does. I think if you're thinking about NREGA, female labor force participation now from economics to anthropology is something that a lot of people are interested in. But often it's like, why are women working or why are they not working? There's less work on what is the experience of work or access to work doing and not doing, at least in my understanding. I think that would be another dimension to think through.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

That's really helpful. Thank you so much, Tariq.

Amrita Kurian:

Can we also take questions from Bhumi just for the sake of time before [inaudible 01:00:39]?

Bhumi Purohit:

Hi, Smitha. Thank you so much. This was really great work and I'm excited to get my hands on your book. I specifically am wondering if you could tease out more how MFIs construct women as autonomous from the household. This builds on Tariq's point about this reputation associated with women as being better repayers, but that also seems in contradiction to the reality, specifically in India, where women's bargaining power vis-a-vis financial decisions in the household is limited. How does this duality work in how MFIs target women?

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

Oh, great question, Bhumi. Thank you. This is something that I looked at a lot in the space of training. My initial interest in this project before I got into this whole mess of financialization and blah blah blah, was actually about that. How is it that MFIs are approaching women? What kind of women do they want to make? How can we observe what the interactions are between MFIs? I picked training as the site to do that because that's when you can really see what are the pedagogical strategies, what kind of materials are they handing out, what is the response from the participants, what does that actually look like? I think that there is a great effort on the part of MFIs to basically convince women that they are financial managers, that they are mothers, that they can be many things, that they can be householders, they can be workers, they can be responsible.

They outline for them in a lot of financial literacy programs that I looked at, and they're often with cartoons and with different kinds of materials. You can be happy or you can be sad. There's a cushy and a snooze, like a zuki and there's a duki. It really calls upon women to be responsible mothers in terms of their management of the financial resources in the family.

I think that is an incredibly powerful framing because it both resonates with women's experiences of being part of households and calls upon them to basically do more to make sure that they are doing everything they can to utilize the loans that they have to make sure they open up a bank account, make sure they utilize the resources that are available to them and all of that. I think the findings are that they call upon them as mothers. There's some different discourses that are out there like you're an entrepreneur, you're a financial manager, you're a worker. There are some competing discourses of that, but they all are very much within. They come back to, in the book, I call it working motherhood. That's the way they call upon them.

I think there's more work to do because of course these things are not stable, and there are many women who reject that and say that, and I talk about that as well who are like, "I don't want to hear about being an entrepreneur. I got to take care of, I got to cook for my kids." People who were entrepreneurs being like, "Why would I call myself an entrepreneur? I'm a woman and I'm a mother and I don't want to be called that. Thank you." It's not that this is something going back to Tariq's comments about heterogeneity and reputation. Women are also selecting how they want to engage with these organizations. They're not just swallowing it whole in any way. I think that's the working motherhood ideal is what MFIs are putting forth, and some women are really attracted to that, and some are just like, "Thanks, I'm going to take care of my family, take your loan and please get out of my life." There's a whole range of ways in which I think borrowers engage.

Amrita Kurian:

Shikhar, do you have something to add?

Shikhar Singh:

Oh, no. I was just intrigued how in recent years there has been this practice of gold-based loans.

Amrita Kurian:

Yes.

Shikhar Singh:

It seems to be all the macroeconomic virtues of it are routinely pirated by the powers that be, but it seems to have some very real implications in terms of who's repaying, who's responsible, and whose assets are going back, if you could say something about that. Thank you.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

Yes. The gold loan thing I feel, I had this whole project that the thing is I can't figure out a methodology, which is why I don't know it, but just follow the gold in India is the ultimate gendered financial project. Figure out what and these gold loans, and a lot of them do MFIs now. They do microfinance. A lot of the gold banks, the gold loan banks also have microfinance wings. I actually studied some of those and I'm a little more familiar than I want to be with some of the inner workings of it cause I couldn't publish a lot of that stuff. They are very, very popular. They are less exploitative than the pawn brokers because they have clear set of rules and there is a procedure. I talk a lot about the standardization of procedure as being a major thing that MFIs put into place that didn't exist before. I think the gold loan folks have done that as well.

They are tapping into very similar constructions of the woman as the ideal borrower who will pay back. A lot of women I talked to got their MFI loans to pay back their gold loans, whether they were with a bank or whether they're with the pawn broker, it's sometimes hard to get that clarity on that information in interviews, but people want their gold back, but they also ponder that's the first thing, the first asset to be pawned. Women are incredibly resourceful about how they use those resources, and yeah, I think there's a whole nother project on dowry, gold loans, how they travel through families, how they get traded, how women get dispossessed of their gold. I'm just shocked that there isn't more work on that. To me, that's just such a good project waiting to be done, but I think the methodology is difficult.

Interviews are not going to quite get at it at, like where do you go and hang out? At weddings where they're exchanging these things? That would be hard to do. Practically speaking, I still have not been able to come up with what would be a good methodology to follow the gold. I really don't know, but I wish someone would do that. Thank you for that question.

Amrita Kurian:

We're nearly out of time. Sarath, do you have a quick question and then we'll come to.

Sarath Pilai:

Yeah, we are already past 1:00, but I'll still ask a question about the historical background because I couldn't help but notice the historical background that you highlighted. One question that I have about that is, because 1880s is exactly the time when there's a lot of financial decentralization is happening with the British colonial state, is the incentive for social banking coming from that decentralization? What is actually driving the colonial state in social banking? I'm also kind of really curious about the role of women in these financial decentralization projects, because women act is usually missing in the story of financial history in colonial India. I'm also wondering about, is the argument that you're trying to make is that whatever the colonial state did with social banking have an impact on how the post-colonial state come to understand social banking? Or is it just a question of giving a historical background? Okay, say looking at 1880s as a point where some social banking existed, but not necessarily shaped the post-colonial banking.

Smitha Radhakrishnan:

Okay. I know the answer to the second question, but not the first. I don't know enough about the history of the British colonial banking, what their enterprise was, what they were motivated by and so on. But the second question is that, yes, I think it's directly related because the fact that the British set up the origins of what ended up becoming the post-colonial banking system, that stratification, we're still grappling with the legacy of that, because of the way that it was set up. That trust deficit, that folks in rural areas just not trusting the lender, of course, that has to do with elite domination and caste domination and land and all these other things, but I think that also has to do with the fact the way the British rolled out that social banking system. I'm not the only one to say, this was a new area for me when I started reading this literature, so it's other folks who have said that essentially there are these long legacies of what happened during that time period.

The British weren't the only game in town. There were other caste-based banking system that I talk about in more depth in the book that were competing for these borrowers, but they all had different kinds of exclusivity. But yes, I think they do very prominently influence the shape of the post-colonial system, and that in a way, MFIs are still figuring out what has been plaguing that for a long time, but they end up solving it in a completely different way.

There is precious little, I searched, but probably not hard enough or long enough for one part of one chapter to find women in histories of banking of British finance. They're hard to find even when you're looking for them. Widows, they show up as widows. We know from the literature on indenture that many women because of financial exclusion, boarded ships because they weren't included and that might have included a banking transaction to actually board an indentured ship. Anyway, I think there's a lot. I probably have to look in other places to find where the women are during that period and what kinds of financial transactions they're undertaking.

Amrita Kurian:

All right. Thank you, everyone. We come to the end of another seminar series. I'd like to thank our speaker, Smitha. Thank you so much for such an exciting conversation.