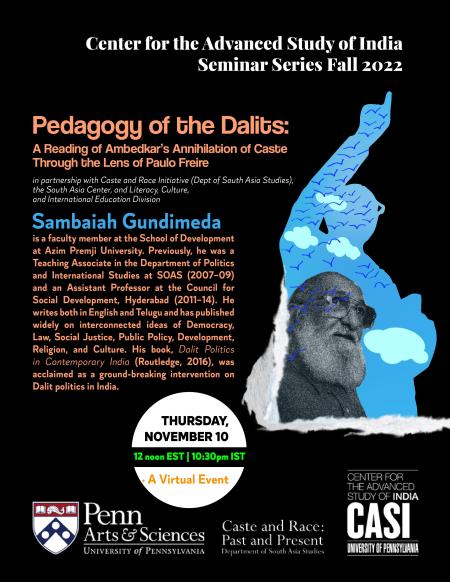

Pedagogy of the Dalits: A Reading of Ambedkar's Annihilation of Caste through the Lens of Paulo Freire

(English captions & Hindi subtitles available)

About the Speaker: Sambaiah Gundimeda is a faculty member at the School of Development at Azim Premji University. Previously, he was a Teaching Associate in the Department of Politics and International Studies at SOAS (2007−09) and an Assistant Professor at the Council for Social Development, Hyderabad (2011−14). He writes both in English and Telugu and has published widely on interconnected ideas of Democracy, Law, Social Justice, Public Policy, Development, Religion, and Culture. His book, Dalit Politics in Contemporary India (Routledge, 2016), was acclaimed as a ground-breaking intervention on Dalit politics in India.

Sambaiah Gundimeda is a faculty member at the School of Development at Azim Premji University. Previously, he was a Teaching Associate in the Department of Politics and International Studies at SOAS (2007−09) and an Assistant Professor at the Council for Social Development, Hyderabad (2011−14). He writes both in English and Telugu and has published widely on interconnected ideas of Democracy, Law, Social Justice, Public Policy, Development, Religion, and Culture. His book, Dalit Politics in Contemporary India (Routledge, 2016), was acclaimed as a ground-breaking intervention on Dalit politics in India.

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Amrita A. Kurian:

Welcome back to the CASI Falls seminar series. My name is Amrita. Sarath, Tariq, and I co-organized the CASI seminar series. I'll be your host for today's virtual event. Before we commence with the talk, a plugin for next week's hybrid event with Saad Gulzar from Princeton University.

His talk is titled Fires: The Political Economy and Health Impacts of Crop Burning in South Asia. You can find the details of the event on the CASI website. A word about logistics for today, the speaker will talk for 35 minutes, which will be followed by a Q&A.

If you have a question, please drop your question or alert me using the chat function. Today's event is co-sponsored by the Caste and Race Initiative of the South Asia Studies Department, South Asia Center and the Division of Literacy Culture and International Education of the Graduate School of Education.

Lastly, it gives me great pleasure to introduce today's speaker, Professor Sambaiah Gundimeda. Professor Sambaiah Gundimeda is a faculty at the School of Development, Azim Premji University in Bangalore. Prior to APU, Professor Gundimeda was the Charles Wallace Visiting Fellow in the Institute for Advanced Studies in the humanities at the University of Edinburgh in 2013, a visiting associate fellow at the Center for the Study of Developing Societies, New Delhi in 2014, and a fellow at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi between 2015 and '17.

A political scientist by training, Professor Gundimeda works on ideas of democracy, law, social justice, public policy and development, religion and culture. In his work, democracy and justice are not just forms of governance or ideals enshrined in institutions, but are principles practiced in society so that citizens are reliably treated with dignity and respect.

He writes for both English and Telugu audiences. His book, Dalit Politics in Contemporary India, published by Right... sorry, published by Routledge in 2016 has been acclaimed as a groundbreaking intervention on Dalit politics. Currently, he's working on a book manuscript that investigates the question of diversity and the constitution of India.

His talk today is his preliminary musings on a very pertinent topic in Indian politics and education and follows the Ambedkar tradition of dialoguing across national boundaries to international scholars writing on social oppression. His talk is titled, Pedagogy of the Dalits: A Reading of Ambedkar's Annihilation of Caste through the Lens of Paulo Freire. Welcome Professor Gundimeda and thank you for joining us. The floor is yours.

Sambaiah Gundimeda:

Thank you, Amrita, for that generous introduction. Thank you so much. So good morning, good afternoon, and good evening wherever you are. Thank you so much for joining the talk on the pedagogy of the Dalits, a reading of Ambedkar's Annihilation of Caste through the lens of Paulo Freire.

Thank you Center for the Advanced Study of India, CASI, the University of Pennsylvania for inviting me to give a talk on the U of CASI's 30th anniversary. Never expected this invitation and for the past few weeks, I've been thinking whether I am worthy of this actually. Nevertheless, I consider this invitation as an honor and recognition of my work if there's anything worthwhile to read.

I, again, thank Dr. Amrita Kurian for following up on the talk with me. She's very kind and generous, and whoever made the poster of the talk that is really amazingly done, thank you so much whoever done that. So now, before I began my talk, I must warn you that I'm still sizzling my thoughts.

Whatever I'm going to present here, it's rather preliminary. My sincere apologies to all of you on that account actually. That's because I'm still thinking about this, bringing these two texts together.

Now that aside, I assume that you joined the talk not because of me per se, but because you are interested in the liberation of Dalits and other marginalized communities, not just in India, but across the globe and, yeah, assume that you're looking for the ideas and ways and means towards the end of... towards that end of liberation or securing freedom to the downtrodden.

And it is that intention and the purpose that brought you onto this talk. Therefore, at the end of the talk, I hope you would share your ideas and insights on the project of the liberation of the marginalized. Now, in the rest of the talk, what I'm going to do is that first, I'm going to present some of the ideas from the text, Annihilation of Caste by Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar.

I'm sure many of you are familiar with these ideas in the text but kindly bear with me. Now, I shall think these ideas, whatever of the ideas from Annihilation of Caste through the happenings in the contemporary India. And then I move on to Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

Now Annihilation of Caste, as we all know, it was a speech written in response to an invitation extended by an anti-caste Hindu reformation group called the Jat-Pat Todak Mandal to speak at their annual conference in 1936. The organizers wished to publish Ambedkar's speech ahead of a conference. And Ambedkar, in his turn, respecting those wishes, sent the text of speech to the organizers in advance.

After going through the text, the organizers hesitated at what they considered sentiments that would endanger Brahminical interests. And so they wrote back to Ambedkar requesting him to remove sections that were unbearable for them. But Ambedkar memorably refused to even a comma.

He went on to publish the speech on his own and the text is now ever relevant and as The Wire some time ago put it, an iconic piece of anti-caste literature. Now, in the entire text of Annihilation of Caste, I shall consider those aspects that Ambedkar specifically pointed rooting out the system of caste.

Towards the Annihilation of Caste, Ambedkar first considered three views, abolishment of sub-caste, interdining and inter-caste marriages. So let me quickly take you through these aspects. The view that the abolishment of sub-caste was based on the assumption that there are similarities of manners among the similarly placed sub-caste.

This supposition was based on an erroneous theory rather than ground realities for according to this [inaudible 00:07:59] of fourfold social order, the Brahmins are the first and the highest of the four varnas and they're the only caste that allow to read, recite and teach the Vedas.

This law, however, is not practiced systematically everywhere and there were counter evidence on the ground in the sense in terms of levels of education, social status and food habits of any caste from any religion differs with some same caste from other regions. And there are castes which, despite their dissimilar location in the hierarchical order, have more commonalities.

So Ambedkar, on account of those divergencies and similarities, preferred fusion of caste which share sociocultural similarities despite their dissimilar hierarchical location to abolishment of sub-caste. I mean, he prefers, and at that point of time, prefers fusion of caste rather than abolishment of sub-caste which are placed similarly in the hierarchy.

In any case, Ambedkar expressed his doubts over the practicality and effectiveness of the method of abolishing of sub-caste towards the abolishment of caste as such you. For abolishment of sub-caste, not necessarily lead to the abolishment of caste system. Instead, it strengthens the caste and makes make them more powerful.

And therefore, what Ambedkar would say would be like more mischievous. Right? Now, the second remedy suggested by social reformers and reform-based social organizations was interdining. Ambedkar rejects this remedy too on the ground that the said remedy neither kills the spirit of caste nor the consciousness of caste, right?

For in the idea of interdining, there is no idea of giving up caste. Each caste goes in its respective separated ways and continue to practice after the interdining event. This was not just Ambedkar's experience or the experience of his time. In fact, in our own times, we all knew the futility of this remedy.

These days, a great number of politicians, either before the elections or during the elections, go to Dalit neighborhoods for meals or sleepover. Rahul Gandhi sleepovers in Dalit locations in the 2009 and Amit Shah's lunch with a Dalit family in the Odisha were well-known examples in recent times.

Such acts do not really create any sense of oneness or equality. Rather, they remind the Dalits their social status as the untouchables and expect them to be grateful to those caste Hindu, upper caste people that visit them. But I always wonder why the caste Hindus come to the Dalit localities.

Why not take the Dalits into their localities, into their houses and feed them in their dining halls? Right? Now, we all knew why they don't do this. They're afraid of that presence of the Dalits will pollute their houses, isn't it? So despite rejecting the first two remedies, Ambedkar was greatly in favor of third remedy, the inter-caste marriages in the direction of Annihilation of Caste.

So the real remedy Ambedkar points for breaking caste is intermarriages. So he was convinced that only fusion of blood alone can create the feeling of being kith and kin and nothing else will serve as the solvent of caste. Yet, he sadly notes that the unpopularity of the idea among the Hindus, there were hardly any inter-caste managers during Ambedkar's time.

Now, the unpopularity of the idea of inter-caste marriage was not just during Ambedkar times, we all know, but even in our own times too, right? Of course, I'm not suggesting that the inter-caste marriages are not happening in contemporary India. They're very much happening in today's Indian society. But the question is what is the attitude of this society towards those inter-caste marriages?

Now, across India and across caste and the religious communities, we come across honor killings, right? For instance, in 2015, as many as 288 people died in the name of honor, and 145 honor killings were reported between 2017 and '19. Recently, world watched rather shockingly the horrific killing of a Dalit man for marrying a Muslim girl in Hyderabad, Telangana State.

So surprisingly, the cases of honor killing are not confined to India alone. As Indians traveled abroad, they're taking their caste along with them. This is something famously said by Ambedkar also, right? To give an example, now some time ago, Subhash Chander who was immigrated to US, Chicago set a fire that killed his pregnant daughter, son-in-law and three-year-old grandson.

During the investigations, he disclosed to the police that his daughter brought shame onto the family by marrying a man from a lower caste. In any case, in recent years, we all knew the presence of caste in the universities and the workplaces in the US and UK. The human cry made by the dominant Hindu communities when the California University system added caste to non-discriminatory policy is very much fresh in our minds.

Now, theoretically, inter-caste marriages should end the caste. Right? But in reality, in most cases, that's not happening. The married couple are not giving up their caste identities even after they're inter-caste marriages. And if the marriage between a Dalit and a upper caste person, in social relations, they use the upper caste identity. They also retain the Dalit identity to benefit economically and politically, reservation facilities and so on.

Now, Ambedkar asks us, why is that a large majority of Hindus do not interdine and do not intermarry? Now, he answers his own question by noting that there can be only one answer to this question, and it is that interdining, intermarriage are repugnant to the beliefs and dogmas which the Hindus regard as sacred.

Now, he went on to state famously that, by quote here, "Caste is not a physical object like wall of bricks or a line of barbed wire which prevents the Hindus from commingling and which has therefore to be pulled down. Cast is a notion. It's a state of mind. The destruction of caste does not therefore mean the destruction of a physical barrier. It means a notional change."

Now, Ambedkar is not finding fault with the caste Hindus for observing caste. Instead, he thinks it is the religion that needs to be blamed for their casteist behavior. Again, I quote here, "It must be recognized that the Hindus observe caste not because they're inhuman or wrongheaded. They observe caste because they are deeply religious."

"People are not wrong in observing caste. In my view, what is wrong is their religion which has inculcated this notion of caste. If this is correct, then obviously the enemy you must grapple with this is not the people who observe caste, but the Shastras which teach them the religion of caste." And I end the quote here, but just kind of pause for a second.

This was known long time ago, Ambedkar mentioned and Ambedkar doesn't want to find the fault with the people. But those people who are highly educated, I mean how do we now explain now those people who are highly educated people practicing the caste actually? Is it kind of, you know... Should we blame them?

I mean, should we blame the religion or we should think that people are exercising caste, are discriminating against Dalits because that gives them a sense of power or dominance, or they just wanted to keep their resources to themselves? And I leave it to you. Anyway, to get back, since it is the Hindu Shastras that teach its followers the religion of caste, Ambedkar vociferously argues the real remedy against caste is to destroy the belief in the sanctity of the Shastras.

Now, he wants us to make every man and woman free from the thraldom of the Shastras, cleanse our minds of the pernicious notions founded on the Shastras. And he or she will interdine in and intermarry without your telling him or her to do so whether to marry or not to marry. You just liberate the people from the thraldom of Shastras.

But the question is like what are the possibilities of destroying the belief in the sanctity of the Shastras? Ambedkar asks in a very straightforward manner, the task of destroying the belief in Shastras, Ambedkar points, is impossible, one, because of the attitude of hostility which the Brahmins have shown towards this question.

The Brahmins form the vanguard of the movement for political reform, and in some cases also of economic reform. But they're not to be found even as camp followers in the army raised to break down the barricades of caste. That's Ambedkar's response. But the question is, again, why Brahmins would not lead a movement against the caste and the sanctity of the Shastras.

Brahmins would not lead a movement against caste simply because the breakup of the caste system is bound to adversely affect the Brahmin caste, particularly the destruction of caste ultimately results in the destruction of the power and prestige of the Brahmin caste.

Now, after exhausting all the possibilities of reforming Hindu society through Annihilation of Caste, Ambedkar considers the idea of conversion. Although, he did not elaborate this in the text of Annihilation of Caste. It is clear that he chose the path of conversion into Buddhism as a path through the emancipation of Dalits.

So he hints at conversion actually in the text and especially, particularly in a speech delivered at the Mahar Conference on 31st May 1936 in Bombay. So he declared that the problem of untouchability as a matter of class struggle, it's a struggle between caste Hindus and the untouchables. So in order to win the struggle, I mean not just this struggle but generally, people require three types of strengths.

One is manpower, the second one is finance and the third one is mental strength. So in the case of untouchables, they have none in terms of manpower or finance or mental strength. So the question is to why Dalits lack mental strength and Ambedkar's point is very, very important.

I mean, one can understand that lack of manpower and then finance, but the mental strength. So he notes that with regard to this mental strength, the conditions of the untouchables are really worse because the tolerance of insults and tyranny without grudge and complaint has killed the sense of retort or revolt.

The confidence, vigor and ambition have completely vanished from... He addresses this from you. All of you have become helpless, unenergetic and pale. Everywhere, there is an atmosphere of defeatism and pessimism. Even the slightest idea that you can do something cannot peep into your mind. So this is part of the address that Ambedkar's mentioning.

But the point here, that normalization of what you call the tolerance, right, against Hindu violence, mental violence, whatever they say that you know completely. Of course, no, you also find that here and there, people rebel. But, well, you know that if people raise their voice or rebel, what would happen.

Now, this is where that he's trying to tell that lack of strength and so on, I mean, the manpower. Now, since strength cannot be gained from insight, that is by remaining inside Hinduism, now, this is important for a number of people for elaboration that they need to gain strength, all that three fronts, the manpower, finance and then the mental strength.

And then Hinduism would not offer all these things, none of these in fact. So Ambedkar tells us that the strength needs to be brought from outside. Okay. If you can't even get it from inside, then go out and then get it from outside. So Ambedkar also states that there is no place for sympathy, equality and the freedom for the untouchables in Hinduism.

So therefore, he urges the Dalits to convert to other religion. Now, we all knew that Ambedkar felt that Buddhism is most scientific religion and Buddhism believe to have met with Ambedkar's complex requirements of reason, morality and justice. Ambedkar's reasons are fine but has a... But the question is, has this conversion to Buddhism emancipated Dalits?

Well, people might have different responses but in my opinion, it did not. Those who converted to Buddhism particularly from Mahar caste remained as an exclusive group. The fate of other Dalits who converted to other religious religions such as Christianity and Islam is also the same.

We know the presence of the caste in these religions, caste-based churches definitely from Kerala and then [inaudible 00:24:19] in the southern pockets. We all know that, caste-based churches, the ongoing struggle of Maharashtra Muslims all confirms us that the religious conversion actually did not emancipate Dalits.

So in our times, we also see that caste-based assertion by the individual Dalit caste and groups such as Kanshi Ram's claiming of horizontalization of vertical social order. These are now taking place. Now, although I am sympathetic to these forms of assertion and understand the claim that such assertions is a way of claiming the equality of caste, and once that equality of costs is achieved, the presence of the caste would be automatically disappears, I do not think that no claiming caste would lead to caste annihilation.

But I also think that such claiming of caste in the name of Ambedkar is simply against the ideology of Ambedkar. Now, given the failure of religious conversions to emancipate and caste assertion to annihilate caste, what is the way forward? Now in here, I think we need to bring in Paulo Freire's ideas from his seminal work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

If one were to read the Pedagogy of the Oppressed and the juxtaposition of annihilation of caste, one would achieve a great deal of clarity on the ideas and arguments found in those two texts. Both the thinkers are primarily interested in the liberation of the marginalized, realizing human humanization in the case of Freire and reclaiming human personality in the case of Ambedkar or at the center of everything for them.

Now, we also get to understand on the consciousness of the oppressor and oppressed in the Indian context, the caste Hindu and the Dalits and other marginalized groups respectively and the machination of the oppressed to his dominance. Now, Freire lays out certain conditions and the principles for the oppressed to successfully break free and liberate humankind. False charity constrains the fearful and subdued, the rejects of life to extend their trembling hands.

This is the sort of point that Freire makes. I mean, one can connect this to Ambedkar's objection to Gandhi's efforts at supporting the uplift of the lower caste, specifically with this word origin. The greater inequality in the caste system, as Ambedkar theorizes, could be connected to what Freire draws attention to, oppressors tend to become sub-oppressors.

So that the caste system illustrates this well where within the lower caste, one can observe an established hierarchy of sub-caste. Here, within the most oppressed caste, there would still be rules for the oppressors and the oppressed. The oppressors would act just as violently and in a dehumanizing manner as upper caste oppressors do.

Well, there are a lot of other aspects that we can discuss during the later part of the talk. But for the present, I would like to concentrate on just the two aspects, the pedagogy and the culture, what kind of pedagogy that one must come up with, a pedagogy that facilitate annihilation of caste or reclaiming of a human personality. And how can we impart the pedagogy among the oppressed?

Now, my first concern is that whether we should call such a pedagogy as the pedagogy of the oppressed or a pedagogy of the Dalits. I know why, in my title, I based it on the pedagogy of the Dalits. I'm actually rethinking on that. So in the month of February this year, in a wide article titled What Dalit People Taught Us About Education and Why We Must Commit to It, Dr. Shailaja Paik suggested the idea of critical Dalit pedagogy.

Now, Paik suggested that critical Dalit pedagogy centers the interconnections between caste, class, public institutions such as education and the private terms like the family, gender, desire, marriage and sexuality from the vantage point of stigmatized Dalit women. Well, largely agreeing with Paik on this, I think one need to go beyond the Dalit category, because the moment one brings in Dalit category a stigmatized category, my concern is that will other oppressed join the liberation struggle?

This is something that one needs to critically think. That being aside or that being said, I want the idea of freedom as the main concern of the pedagogy, why Dalits and other marginalized or limited in every respect while caste Hindus dominating in every aspect of life in India? Why is the oppressed [inaudible 00:29:37] things essential to a decent and dignified life?

Why Dalits struggle for everything, spend a great amount of time fighting among themselves for resources, for accessibility? Why caste Hindus act as though they're smarter than the marginalized? So attempting to answer such questions, questions that arose from the lived experiences would help us or would help them to see what is fabricated and what is reality.

Now, Paulo Freire, while explaining the consciousness of the oppressor, points out that the... to one of the powerful methods that the oppressor use insidiously to keep their dominance as that of the cultural invasion. Now, they utilize what, in a sense, is a temporary state of subjugation to convince the oppressed of their inherent inferiority and position themselves as the superior whose values and culture the oppressed must now learn if they are to have any hope of developing [inaudible 00:30:50] through this neocolonialism.

We're all familiar with this, how the British actually colonized the cultural colonization and so on. Now, the oppressed come to look at their existence and the world from the lens that the oppressor have imposed on them and they begin to adopt their beliefs and behavior. And in doing so, they stop thinking inherently and being their own person and thus unknowingly helps strengthen the oppressor's grip on their own lives.

I think one needs to take this insight of Paulo Freire rather seriously and examine the cultural colonization of Brahminism, right? Why is it that all the Hindu festivals celebrate the victory of the caste Hindus as if Dalits don't exist or other marginalized don't exist in here. Why there are no specific Dalits and other marginalized festivals of national significance?

Has it always been like this? I mean, what kind of cultural life that the so-called untouchables and others were having prior to the Vedic period? Why is that the cultural life is completely erased? Why there is no cultural life at all? I mean, the cultural life means this is upper caste and then lower caste seeing their cultural life through the oppressors' lenses. Right?

Now, I think reclaiming culture of indigenous community prior to the Vedic period might help. Just the idea, thoughts might help the marginalized in India to reclaim their lost human personality and developing a culture of their own, which is built upon the principles of liberty, equality and fraternity also facilitate the path towards humanization. And I think I'll stop here and then I'll leave it to you. Thank you.

Amrita A. Kurian:

Thank you so much, Professor Gundimeda. So now, we are open for Q&A. I do need some time. I'm thinking about a question for myself. If you are ready with a question, please drop it in the chat or let me know if you're interested in asking. Tariq.

Tariq Thachil:

Yeah, sure. Thanks so much Sam for that very thought-provoking talk, and I'm still processing myself. But just a couple of points that you made that I'm just trying to react to and think through with you, the first was when you talked about Ambedkar's blaming of religion.

I thought that was quite interesting, this idea that it's not about the observation of caste and caste hierarchies as being about someone's inhumanity, but about their deep piety or their deep religiosity. And I was trying to think through how that squared.

I mean, is there... There seems some kind of, to me, theoretical and philosophical tension between that observation and how he talks about graded inequality. And so the very commonly quoted passages of Ambedkar on graded inequality to me seem like they often are talking about... not just about piety, but about the deep kind of human need for hierarchy and the deep attraction of, if not inhumanity, then the deep human need for hierarchy.

And so to me, there seems to be a tension there, and I was interested in whether you saw it as a tension or whether this passage that you quoted, how you read it against other kinds of portions of Ambedkar trying to analyze why there is this observance of caste. Because that's the question that you're relaying here like, "Why is there this attachment to the practice and observation of caste among privileged Hindus?"

And that was something that I couldn't quite fully figure out. The second was this kind of question I had about a lot of what you are thinking through is in the language of politics or at least the worlds that I study, often a question about... It is a question also about thinking about aggregation and coalitions, and about broadening the umbrella of exactly your question about your ambivalence about calling it pedagogy of the Dalits.

At some point, it is a question about how to build broader social coalitions. And I've really been thinking about what happened, what can we learn from the experience of what happened with Bahujan. I mean, you mentioned Kanshi Ram, but the whole move from DS-4 to Bahujan Samaj Party was this idea of some kind of more aggregative category.

And at least from recent politics in UP itself, what seems to have happened is its death by the most micro level of splitting within... as you talked about, within varna-jāti splitting in candidacy or the painting of the BSP as not just feeling as a Dalit party, but really a party of subcategories within Dalits.

And so there, I think there's a lot of impressions around how much can we look at sub-caste eradication. And far from being eradicating sub-caste, sub-caste have, in fact, eradicated these attempts at larger political coalitions, not just Bahujan, but even in some ways, a Dalit.

I mean to talk of a Dalit vote in UP at least right now, I don't think really makes a lot of sense. That isn't a 'Dalit vote' in that same way. So I was just wondering how you think through. So this is not as pointed a question as I would like, but these are two reactions, one more theoretical and philosophical on Ambedkar and thinking through tensions within him.

But the second is how you reflect on the kind of failure of what seemed like one attempt to broaden a kind of social coalition and where it's ended up, and what that means for what you're thinking now.

Sambaiah Gundimeda:

Shall I respond? Yeah. Thank you, Tariq, for that question. So the first question regarding this blame religion and then graded inequality thing, well, I didn't actually thought about this, but I see that tension. But I'm not sure whether Ambedkar or... I mean the idea of that graded inequality as a facet of the deep... I mean, clamor for superiority or dominance of the human beings.

I think if you meant to, you can say he said that it's religion to be blamed. Even that graded inequality also, he would blame a religion itself but not the human psychology to clamor for dominating. That's what I would suggest because if he's blaming religion in one place, then I think he would blame the religion for that kind of behavior elsewhere also.

But I don't really agree with Ambedkar on this point actually. The moment that you completely blame religion, you can do anything with that, "Oh, this is kind of... My religion is what is doing here?" Right? You're not, what you call, holding the responsibility of the person's actions right. You can practice caste and untouchability and then say that... You can blame upon this religion. And so I don't agree with the Ambedkar on that, but while I understand that where he is coming from, but I don't really agree with that, I think.

And I think it's a really challenge on this coalitional front where the way actually the BJP and then RS are really entering into this each and every caste, and then able to know divide whatever the Dalit-Bahujan coalition that the BSP built over a period of time.

So particularly the way they entered into this sub-caste of Valmikis, for example, using their own cultural ideas and then giving them a space, or constructing a sort of Valmiki Mata or some sort of figure, cultural figure for them, and then assimilating that figure into this Hindu pantheon of gods and so on, the way they went, and then equating that we are all Hindus and one.

Never talk about the caste. It's all about religion and so on. They've managed to break that. So honestly, building in a coalition, I have no idea how to do this actually at this point of time, how to rebuild this new coalition, whatever happened.

But I think the whole idea of... I mean, if you take this idea from Pedagogy of the Oppressed or any insights, there is a possibility bring the people together again around the lines of oppression, that some of the questions that I post that why you are lacking, why other people are lacking, I mean, critical thinking through their own lived experiences.

But it's kind of... It's going to be a long road, a very painful road, in fact, I think very challenging, but it has to happen. If one wants to break this Hindutva onslaught or Hindutva dominance on these marginalized mindsets, I think now that has to be done.

Amrita A. Kurian:

Thank you so much, Professor Gundimeda. I had a question and after me, Jusmeet also has a question. So solidarity projects and solidarity across oppressed classes, it's something that I think scholars in the United States have thought about quite a bit.

But as somebody who's an educator in India, and I know you're just beginning this project and you're probably like you're mulling through that yourself, as an educator in India embedded within institutions of the oppressor, how do you put in line... How do you put into your practice or into your teaching some of these ideas of critical pedagogy that you're talking about or the Pedagogy of the Oppressed in that sense?

Sambaiah Gundimeda:

Thank you, Amrita. So in the subjects that we are teaching in our universities, we don't really come across the ideas of caste oppression, humiliation, all that. Right? So I think one way of addressing or making some sense of what's happening around, including some of these themes into the pedagogical or into the teaching, I don't know how one has to do that, given that new education policy.

But at least some of the university... In Azim Premji University where I teach, I now have a paper or elective which talks about diversity, and then I bring in some of these questions, you know? So some universities still retain that independence but now, I don't know how long they can retain that independence.

But it's very challenging given that people are actually casteized. People are completely come with the baggage of caste mindsets and then the religious mindsets. Divisions are very clear. Divisions are very clear. And then maybe in the classroom, they might put up as one, as a group of students, but it's very clear that people are divided on those lines.

Now, I think it's very challenging. Yeah. Well, I don't know. One has to really think. But some universities, yes, at least they allow. But a lot of other universities... I don't know whether I'm answering your question, Amrita.

Amrita A. Kurian:

No, no, no. I was just wondering because as an educator, I'm constantly thinking about ways you can actually teach to the oppressed to bring in critical consciousness. But often than not, institutions themselves form the choke hold for those.

Sambaiah Gundimeda:

One of the problem is that when very recent... I mean, when we talk about the subject of Dalits, let's say, or communism or, let's say, secularism, it's mostly marginalized communities and the Muslims and the Christians would be joining in these little themes, either in talks or... Definitely the caste Hindu students, I mean, as if this is not relating to them. Right?

So that is what happening actually. So it's, again, a challenge. I don't know how to handle. I mean, if people actually show some kind of interest, then we would be able to take them towards this experience of understanding their own self. See, what happens, the moment that you talk about caste in Indian classroom context or... It hits. Right?

It hits everybody particularly a majority of the students come from these upper caste backgrounds. You take any private university or private college or private institution, it hits them. And so now, the complaint against the faculty member who teaches these either caste question or asking them to reflect upon their own caste, they would say that, "This guy is dividing."

Then he would get call from the registrar. This is what happens actually. I mean, it's also now very, very easy, now with the Hindutva, everything that hurts sentiments. The moment that you talk about religion or caste or anything, that you're hurting the sentiments. It's easy to put in that, and then you are dividing.

We are not... You're against or anti-Hindu or you're not a nationalist and so on, some of these ideas, kind of ready-made the responses that they would bring in. It's very difficult to actually making the students kind of... to make them to think where they come from, how they come from and so on, why other people are lacking, why some people are having a lot than what is required and so on.

Yeah, I don't know. I'm not sure whether this... we would able to bring in some of these questions in the near future, especially if BJP is going come back to power in the future, this elections. And the screws are tightening everywhere.

Amrita A. Kurian:

Thank you so much. We have Jusmeet in line for a question, Jusmeet.

Jusmeet:

Hi, Amrita. Thank you so much. Once again, sorry, I won't be able to switch on my camera. So thank you very much, Professor Gundimeda, for this very fascinating talk. I wanted to of build on the last point that you ended your talk on about the cultural sort of argument that you're making, bringing the culture back out from Vedas.

So I wanted to give you one example from the feedback that I noticed and one observation from the Vedas. I'm not a scholar of Vedas at all, so I may be completely off track on that, but I think the little reading I have of Vedas is that sacrifices constitute a very important part of the Vedic cultural practices.

And in my field work, I could, in fact, see a lot of practices of sacrifices of goats or sheep involving blood and so on across the different sub-castes amongst the ex-untouchable category. Right? Now, these practices within a city context are being practiced but are being practiced in a very, very hidden way, in a hidden environment.

There is no way that even nearby upper castes or middle caste or OBCs even would be able to accept this kind of sacrifices. So how do you bring that tension out and, again, get something which is considered a polluting kind of an activity or a ritual to be accepted by people where sanskritization is of widely practiced?

And a second small point I had about pedagogy was about why not use storytelling as a way to empathize students into this critical pedagogy of caste? So an example, for instance, Omprakash Valmiki's, Joothan or even mainstream novels such as Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry where there are very, very powerful passages on caste.

And I think it has a very, very strong impact on audience on humanistic grounds. And I was wondering if you see this kind of an approach as a good idea to introduce people into caste, and then you can bring more challenging questions about graded inequality or sub-caste divisions and so on and so forth. So thank you very much once again. It really made me think a lot, so looking forward to your answer.

Sambaiah Gundimeda:

Thank you, Jusmeet, for that. Actually, I think of this storytelling as one idea. I'll give that credit to you. I'll think about it more clearly on that front. And great suggestion. Thank you.

The first aspect regarding this sacrifice, I mean, now to bring these people together on the idea, I don't know. I mean, I think one need not exactly follow some of these practices which is maybe not everybody's been following.

I mean, for example this idea of sacrificing, and then some people do, some people don't do and so on, do we really undertake our... bring people together on the base of this sort of activities, claiming that this is part of our pre-Vedic cultural life?

I mean, some of these things, some ideas we can bring in but not all the ideas. But I don't know what are those cultural practices actually. That is, I mean, dilemma. My idea is that that gives them a self-affirmation at least that we had some sort of culture before all these cultural practice [inaudible 00:50:49] being imposed on us, what kind of culture we had.

There was something, maybe not everything to do with the sacrifice and maybe something better than this. So some of those ideas, if they can bring in and then tell all these... not just the Dalits but then the OBCs and then other communities that we had some common cultural practices which just give us some sort of value in our life.

Jusmeet, again, I'm just thinking again. As I said, not that clear on that front, but let me think on that idea. But my only response is that we can give up some of those practice. We don't have to assimilate all those practices that... what these pre-Vedic period people used to practice, some of these, kind of very relevant, some of these things which is... would bring people together. I think we don't have to completely follow as it is. Right?

Amrita A. Kurian:

Sarath, do you have a question?

Sarath Pillai:

Yes. Thank you, Professor Gundimeda, for the talk. I have a very broad question and I don't know how to put it. But one thing that strikes me from your talk is it somehow seems to me that the project of liberating the Dalits or the oppressed seems like a liberal project that is reliant on certain conceptions of state constitution, rule of law.

So in some way, especially in the context of Ambedkar, I find the role of state and law is very central. And I'm wondering what is the role of a state and law when it comes to Paulo Freire, for instance? And I'm generally wondering because I think even Tariq's question about coalition or building alliances is particularly important if we think of the importance of state and law in finding certain kind of solutions to the problem.

At the end of the day, we need to think about who's going to legislate and how do you have a say in the process of legislating something. So I'm basically wondering about the importance of even conceptions like rule of law or state and law in this project, especially in the context of the two thinkers that you were talking about. Thank you.

Sambaiah Gundimeda:

Thank you. So I'm not so sure about Freire's ideas on state, but about Ambedkar, he invested so much energies into this state and then laws and governance, constitution particularly. Right? I mean, he saw that... I mean, emancipation not through the state itself.

As people are dispossessed, state is the only path, I mean, the state as a facilitator for the emancipation. State has to be at center for everything. Without state, you know... He was not relying upon this, what you call, traditional society or traditionalities and so on.

He's completely depending upon this modernity and state or the state as an agent of development as well as emancipator. But while this might really surprise, again, that while he invested in so much of energies into this state and then concentrate on constitution, but at the end, his conversion, actually something that [inaudible 00:54:50] puzzling.

So I think one has to understand and know from two perspectives. One is where conversion as emancipation where he states that... There are two points that he mentions. One is for material gains and the second one is mental gains in the sense like strength, manpower and so on. There's also spiritual salvation.

Now, I think in the materials gain, you would want to know, depend upon the state where for the spiritual salvation or spiritual liberation, I think you want to go into that direction. But definitely, state should be at the center. Now, again, state also failed to liberate Dalits, right? State has miserably failed to... Otherwise, we wouldn't be talking about Dalits per se, today's talk. Right?

State has... I mean, we are relying upon state, but state did not liberate or did not play the role it's supposed or expected to play. Again, look at this BSP's... Mayawati became four times chief minister of Uttar Pradesh. And now, we are actually back to square one in the way we started in the center with regard to this Dalit-Bahujan politics. Right?

So the BSP did not focus upon some of these issues. I mean, maybe they tried to bring people together and then some of the council events or construction of Ambedkar Museum and so on, park in Lucknow and so on. That is done. But I think they did not really deeply invested on the idea of culture.

And this is where the BJP and then RS would be able to reenter into and then break this whatever kind of peripheral... the coalition that taken place at that point of time. I mean, while I agree with that, state is important. But at the same time, I think the emancipation, cultural emancipation has to happen simultaneously.

One can answer that which is the first and which is second? I think it has to happen simultaneously. I mean, why they're not there... I mean, Dalits are now hither tither, everywhere. They're not one group of people now. They can be divided on the basis of caste and sub-caste other than the people who are having reservation, people who do not access reservations, people who do certain occupations, people who do other occupations and so on.

In every aspect, they can be divided. But if there is some sort of common culture, that culture would've brought these people together. That would've welded them together. Something lacking there, and that is where the BJP swept into that empty path, I think, empty space. It's where... Yeah. So in a way, you know that what I'm trying to say that... Sarath, I don't know whether I will be able to respond to your question.

But state is important, but at the same time, culture, cultural life is also very important because in order to make the people to... I mean, especially to retain the political power, if political power gives them material goods and so on, in order... Even to retain that political power, that people have to have that cultural resources. So the lack of cultural resources are what led to this state of condition now. That's what I think. Thank you for the question.

Amrita A. Kurian:

We'll take a final question from Lisa.

Lisa Mitchell:

Thanks, Amrita. Thank you so much for this really important discussion, and it's really nice to see you here. I wish you could be here in person. But this'll have to be second best. I also want to return to this question of the cultural and its relationship to the political and its relationship to pedagogy, which you so nicely framed in your talk.

And I know you've done research on some of the experiments in trying to make festivals into pedagogical events. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about, for example, the Sukoon festival at Hyderabad University and the way that the beef stalls that were incorporated into the Sukoon festival functioned as not just as a political intervention, but also as a pedagogical intervention.

Could you say a little bit about either that or other festivals that have actually tried to make a pedagogical intervention?

Sambaiah Gundimeda:

Yeah. Thank you, Lisa, for that. Nice to see you again after so many years. So of the beef festival in Hyderabad Sukoon festival, I think that's very, very really important because this is where Dalits... It's not just about beef eating. It's about claiming a space in the university space. You know?

Hitherto, the university space is occupied by this... the vegetarian community or the Brahmins, the upper caste and the caste Hindus largely. But now here, Dalits are claiming that we also have a space. And then now, food is one accessible accessory, food. I think that's very, very important.

And then there are other, these days recently, other festivals through which Dalits are trying to reclaim a space or counter Hindutva onslaught. For instance, bringing the [inaudible 01:01:03] of the Mahishasura, the figure and then... And also the questioning of the way they celebrate Diwali, whose festival that is and so on.

And then the discussion and debate around the Ravana, the personality of... not personality, persona of Ravana and so on as their own god. And then when caste Hindus actually killed Ravana during this Dussehra, Ram Navami festival and so on, the Jayanthi, that Dalits began to claim that, "Okay, if saying anything against Lord Ram hurts your sentiments, even Ravana is our God."

And you are actually setting a fire about his efficacy. And so that also hurts our sentiments. So in a way, we see that there's what you call the project of cultural homogenization is challenged by the marginalized. You know? While they're trying to homogenize the Indian culture through these cultural means like festivals, for instance, let's say, Durga Puja or Ram Navami and so on, but these people are also challenging this, that we don't really follow same festivals.

We have different takes on that. The claiming of diversity actually, we have a different take on. I mean, again, it's a claiming of what you call their own space and also challenging the dominance, challenging the dominance of the Hindutva forces, I think. Yeah. I mean, that's very powerfully being drawn. But of course, that has to be supported by the political power. Right?

You require a political power even to bring anything. Now, you say something that people are being arrested and then now put behind the bars for years together. And so despite that and lack of political power, still, people are figuring out ways and means for challenging this homogenization project of the RSS and PS, BJP. Thank you.

Amrita A. Kurian:

Unfortunately, we have run out of time. Thank you, Professor Gundimeda for this engaging talk, but importantly, for sharing what's your work in progress. I hope that this discussion was of some use to you and you take something from us like we did from you. Until next time, this is it. Let's all thank Professor Gundimeda for this lovely talk.

Sambaiah Gundimeda:

Thank you. Thank you so much for this opportunity again. Nice to see you all.