Data and Democracy Deficits in India: Are Innovation and Accountability at Odds with Each Other?

Center for the Advanced Study of India

Ronald O. Perelman Center for Political Science & Economics

133 South 36th Street, Suite 230

Philadelphia PA 19104-6215

*Masking is optional*

(English captions & Hindi subtitles available)

About the Seminar:

Over the last few years, India has seen both a rapid expansion in the availability of some government data, as well as significant restrictions in the availability of some essential data including on employment, poverty and covid mortality. How and why do the two exist simultaneously? What levers of the democratic process are necessary to push to make more vital data available for citizen participation and decision-making? Do new attempts to harness data privately represent the best of Indian innovation, or do they lower democratic pressure on governments to provide data that is the right of citizens - or is the truth somewhere between the two? How can the different pillars of democracy collaborate to fill in these deficits of both data and democracy? Rukmini S will draw on both her experience of being a data journalist in India as well as on work from her book to consider these questions.

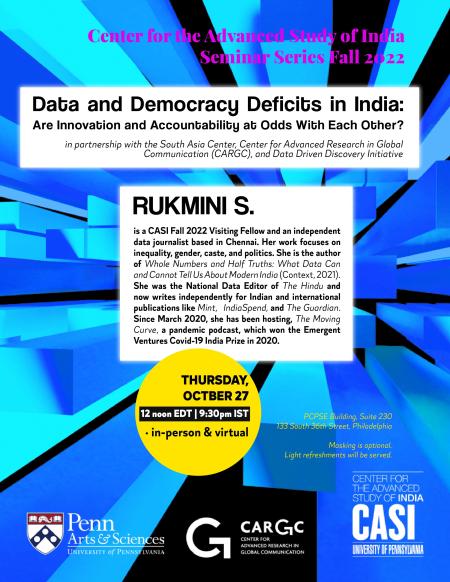

About the Speaker: Rukmini S. is a CASI Fall 2022 Visiting Fellow and an independent data journalist based in Chennai. Her work focuses on inequality, gender, caste, and politics. She is the author of Whole Numbers and Half Truths: What Data Can and Cannot Tell Us About Modern India (Context, 2021). She was the National Data Editor of The Hindu and now writes independently for Indian and international publications like Mint, IndiaSpend, and The Guardian. Since March 2020, she has been hosting, The Moving Curve, a pandemic podcast, which won the Emergent Ventures Covid-19 India Prize in 2020.

Rukmini S. is a CASI Fall 2022 Visiting Fellow and an independent data journalist based in Chennai. Her work focuses on inequality, gender, caste, and politics. She is the author of Whole Numbers and Half Truths: What Data Can and Cannot Tell Us About Modern India (Context, 2021). She was the National Data Editor of The Hindu and now writes independently for Indian and international publications like Mint, IndiaSpend, and The Guardian. Since March 2020, she has been hosting, The Moving Curve, a pandemic podcast, which won the Emergent Ventures Covid-19 India Prize in 2020.

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Tariq Thachil:

Hi everyone, and welcome to CASI, the Center for the Advanced Study of India. I'm Tariq Thachil, I direct CASI, it's lovely to see you all here. Most importantly, for those in person, please feel free to grab kati rolls and coffees and fortify yourselves for the talk. Those of you on Zoom, sorry, but we haven't figured out the tech to get kati rolls to you yet. Maybe we won't, because then you'll never show up. It's a great, great pleasure to introduce our speaker today, Rukmini S., who has been a visiting fellow with us at CASI for the past month, and on the eve of her departure is giving this talk, which we're very excited about.

I mean, don't need to introduce her to many of you, but I will say that she's a independent data journalist who's based in Chennai. She's been working as a journalist since 2004, worked for many publications including the Times of India. She worked for the Hindu as national data editor, where I believe that was the first data editor in an Indian newsroom at the time, so really was a pioneering position. She's worked for a number of outlets since, including HuffPost, Mint, IndiaSpend. She currently is a independent journalist who has bylines for a number of these publications.

But what's really been interesting about following Rukmini's work is how she's really married a reporter's ability to nose out and procure data that will be inaccessible to many of us. But also the ability to analyze that data like a researcher and then communicate it very much not like a researcher, we tend to be terrible about that, but in a way that's publicly accessible and easily digestible. There are too many projects for me to list, but she's worked on understanding data from India's religious census and context, often upturning false narratives fueling Islamophobia. She's analyzed cases of sexual assault to uncover often a lot of nuance in what police statistics reveal, and importantly what they don't.

Most recently she's done pathbreaking work during the pandemic, locked down in her house, reporting really numbers using and creating public-use datasets and creating a very popular podcast. I'm sure many of you have heard it, and if you haven't I recommend it, The Moving Curve, which at the time just gave excellent distilled insights from experts on topics ranging from testing to mortality statistics at a time which was very uncertain and confusing where we were all not quite sure what information to believe and what not to believe. Her reporting is really informed, not just I think public discourse, but often scholarship as well, which I think is really important.

She's been awarded prizes including the RECO Award for excellence in media, for data-driven reporting, and in 2020, an honorable mention for the Chameli Devi Jain Award for outstanding women journalist. Finally, and most importantly, for today's talk, although she's already drawing on some of this, is the author of a recently and justifiably best-selling book Whole Numbers and Half Truths: What Data Can and Cannot Tell Us About Modern India, which was published in 2021. It's been longlisted already for the Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay New India Foundation Book Prize, and we are delighted to say that we have some complementary copies for anyone who's interested, over there. First come first serve, after the talk. Please don't try right now. I'm not sure if she'd be willing to sign a copy for you, but maybe for a small fee. CASI gets 20% overall.

Mostly, Rukmini, thank you for giving so much of your time at CASI. You've engaged with so many of our students, faculty, and staff, in ways that I know have been really enjoyable for all of us. It's a pleasure to welcome you for this talk, so thank you and I put the floor to you. Before I do so, though, if you're online and you have a question, just drop it in the chat and we're actually going to read it out when it's time for the Q&A after she finishes speaking, just to make it go smoothly. Thank you, and thanks again, Rukmini.

Rukmini S:

Thanks very much for that, Tariq. It's so great to see this audience here, as well as online. I'm going to present us with the kati rolls, have not had them [inaudible 00:04:21] all of you been here. But it's also great to see people from multiple parts of my month here so far, really, it's great to see people I've met discovering to city, undergrads from disciplines who I don't usually interact with, grad students, post docs, and most importantly my family here at CASI for the last month. What I'm going to do today is, I don't want to talk about the book alone, and I don't want to talk about data alone, but I do want to talk about some of the issues that both the book and my work around data journalism have allowed me to think about and spring up. Looking forward to questions, particularly from the students, including those online, at the end of the talk.

As you see, I'm pulling in the question of both democracy and data, and shortcomings, in both in the current moment in India right now. I would like to talk about this. I also welcome questions from it, but I am driven by a what-can-we-get-done spirit. I think you'll find that in a lot of [inaudible 00:05:35] we talk about there are issues, we can discuss them, but I am most focused on what we can do given what we have. I'm also delighted to see how much the spirit runs through young people I meet both in India and... It was a pleasant surprise to me here as well, the spirit of, "These are the skills I have, what can we do with it?" I'd be happy to talk about that at the end of the talk as well.

As Tariq mentioned, I've been a journalist for a while now. As a rookie journalist straight out of journalism school, this meant basically having to do what rookies and all professionals, hoping to scratch furthest reaches of the city I was in at the time, Mumbai, and increasingly the rest of the state and the country. Reporting from police stations, courts, government offices, slums. While I didn't think perfect at the time, I think what that experience did was to show me how the nuts and bolts of Indian democracy actually operate and encount. I think in the moment then I [inaudible 00:06:38] names in such a grand terms, but in hindsight I feel like that's what that experience did.

This became particularly valuable when I made a shift to data journalism some years down the line. I have never studied maths, stats, politics, economics, anything particularly useful. So when I did a masters in development studies at one point, it was the first time I was ever exposed to research around India and South Asia, quantitative, qualitative, numbers, all of it for the very first time. When I returned to India, I felt that I wanted to incorporate all of this great research I was encountering, into the journalism I was doing. The first example for me then, the first assignment I was dispatched to do was to cover food insecurity in an extremely poor region of central India. Because this was the time that the crisis of essential food commodities had begun to escalate, and this resulted in people constricting their own menus and household budgets.

The usual way of reporting this sort of stuff is to parachute in, usually from a big city, and talk to whoever catches your fancy and come up with that as a broad take on the situation on the ground. But for the first time it now occurred to me that I now knew that if we has a Global Hunger Index, perhaps I can incorporate that. I knew that there are places I can go to look at consumer and wholesale prices of say naan, and incorporate those increases into my reporting. That's essentially what led to data journalism. I don't think I even thought of it as that term at the time, but that's what it's been in the 10 and more years after that.

It ended up coinciding with the ascendance of Indian data journalism, which came out of a number of factors including editors realizing that readers were sensing a real lack of rigor in what they were reading, which was essentially he said, he said reporting and there was a sentiment among readers that editors were catching up on what they wanted more rigor, and data perhaps could have been one of the ways to think about there.

The book came out of... I like to pretend that this very illegible slide is on focus, but that makes people buy the book. It's essentially the contents page. The book came out of my feeling that I wanted to put it together, these two sets of experiences. Which again, I didn't think of it at the time, but perhaps they were qualitative and quantitative experiences, experiences on the ground and in my work as a data journalist. What I've tried to do in the book is ask 10 big questions about how things work in modern India, from things around the economy and politics, to also general crime vast health. Try and look at what good data can tell us, as well as what the data often misses because of a lack of context, what the data can somehow mislead on, and what are the sometimes truly damaging and dangerous consequences of a failure to fully understand the context of Indian data.

One of the reasons I focus on the word good is because there is sometimes a sentiment, particularly among people who do work with Indian data and often among young Indian data journalists, that there is no good data in India. That the data is so old, so difficult to access, it can't possibly tell you much about India. I like to remind people of the founding moment of not just India, but Indian statistics itself, because it has in a way a role to play in why Indian statistics look the way they did today. The Indian statistical architecture that was put in place after independence was audacious.

Neither of these two men, Nehru and Mahalanobis, really had much right to dream of a statistical architecture that was so much more audacious than then levels of implement development we had at the time. Part of the reason India statistics look as they do right now, both the good and the bad, have to do with that moment and the way that architecture was put in place. I encourage people to think more about the moment of putting together congested statistical architecture, the problems it was trying to solve for, and to think about how well the house that Nehru and Mahalanobis built has held up, and perhaps what we need to do to shore it up now.

Those five big themes I'm going to race through in my slides, because as I said, I'm very keen to be questions. The first one, as I mentioned, is that there is a lot of good data around India. One of the reasons in particular I like to remind Indian elites, of who I am a card-carrying member, of this that there is good data, is because there's sometimes a feeling, less so with people who read the data but more so amongst the Indian editors, that numbers are something cold in spreadsheets on paper. The real India is the one I encounter, and that is, numbers don't get it. What you end up with is the bubble effect that's extremely strong among the Indian elite, and I like to confront them with some of the numbers that good Indian data... some of the findings that good Indian data can lead us towards.

For one, there is this extremely ossified way of thinking around Indian politics, which to my mind comes out of repeatedly looking at very mediocrely conducted surveys around opinion polling around India. These are surveys without inner ambition and I do believe that the answers have been repeatedly taken at face value, producing a notion of the Indian voter that is in many ways quite far removed from how things are here on the ground. For example, the Indian media has a morbid fascination with money in Indian elections, the conviction that votes can be bought and sold in India. One of the sources of data that does exist that's rarely looked at is beliefs of voters around ideological lines. This chart, for example, compiled by the political scientist [inaudible 00:13:01] shows that Indian voters, particularly for the two largest parties, are remarkably ideologically consistent.

This association of ideology and ideas with Indian elections, it's a sort of respect that we rarely occur to the Indian voter. We rarely think of the world of ideas and ideologies, particularly in the Indian media where you're talking about voters. For example, I found... I talked to two women voters before the Tamil Nadu election. They had both the same money from the party they intended to vote for. My argument is that the media often stops short right there, that's where the interview ends. But both of them had moving answers for why they were voting for the party they wanted to vote for. One of whom said that she wanted to vote for a party led by a woman, so in academic terms perhaps you would see it as a feminist vote. The other one wanted to vote for a party that she believes represents justice and centralism. Again, elevated concepts that we sometimes do not associate the Indian voter with.

I also like to confront members of the Indian elite with data around caste, because there is sometimes an emotion that caste no longer underpins with Indians' lives, it's a rural construct, it's a relic of the past. I like to remind people that the inter-caste marriages that they see in the world around them are not representative of the broader country. Just 4% of Indians are in inter-caste marriages now, and this number is unchanged from independence. The way Indians in their 20s get married, arranged marriages arranged within caste, is essentially unchanged from the way their grandparents were married. Again, this is a reality that I find Indians are often unwilling or unable to put in front while the data has shown us this for a long time now.

Sometimes this lack of accurate, adequate attention to data that does exist leads us in particularly damaging directions. I believe we went into the pandemic without an accurate understanding of the way Indians fall sick, and the way they access health, even in peace times let along during a pandemic. For example, we went into a pandemic, we went into the first wave of the pandemic and there was a sense of what [inaudible 00:15:25] calls the superhuman Indian poor. The feeling that noncommunicable diseases, for example, affect the rich and don't really affect the poor and this explains why they're seeing such low rates of COVID mortality among the poor, and poorer Indian states. Of course, as we've gone through the pandemic we've seen that it's probably a case of the numbers not having captured what was really going on. We shouldn't have had this question at all, because we should have gone in knowing that noncommunicable disease significantly affect the poor as well. These are no longer lifestyle diseases as we once understood them. All of this went on to, I believe, harm our pandemic response.

That's the question of not paying attention to good data that we already have. But in my mind, the most damaging aspect of the way data is consumed in India is the lack of context with which data is presented, leading to extremely dangerous and damaging directions. Nowhere is this more apparent to me than in the discussions around sexual violence that began following the brutal assault of a young woman in Delhi in 2012. There was this national outpouring and the sense that a long overdue conversation had finally begun. The extreme levels of unsafety and violence that women have been experiencing had not made it to political conversations and public discussion, and there was a sense among women that we need to have it and it really worst fought from women all across the country.

But one of the things that happened in the analysis of this moment, was that we began to use police statistics as proxy for crimes against women. I want to make a two-step argument about how dangerous I believe this is. On this chart, which was put together by the demographer, Aashish Gupta, on the horizontal axis you see violence as reported to the police, per capita, where different Indian regions. On the bottom right you see, for example, Delhi. Delhi is one of the states over here. When you focus very heavily on these police statistics, what you have is a policy response that means more street lights and data policing for example, for what is already one of the richest parts of the country, one of the best-funded parts of the country.

On the vertical axis you have violence as experienced by women as they say to household surveyors. This is completely separate from police statistics, this is through the demographic and health surveys. Of course, expecting that these surveys accurately capture the full extent of violence as experienced by women would be wrong and disingenuous, and that's not the argument I'm making, but I would say it's one step beyond looking at police statistics alone. To me, the most worrisome quadrant in this chart is this top left one, because that is the quadrant of states which report the lowest levels of violence to the police whilst simultaneously having women who say that they experience the highest levels of violence. There's two problematic processes going on simultaneously, lower reporting to the police and high experience of actual crime.

But without this triangulation that you're unlikely to see, and I must say not just in the media but also in a lot of academic work around violence against women, when you don't pay attention to that quadrant I think it means that we had in Madhya Pradesh, two of the poorest states that live in that quadrant, get left out of the national conversation. There is a further deeply damaging dimension to the conversation around violence that began in 2012. My experience of having been a pure reporter reporting from police stations led me to believe that using the FIR, the first information report which is the initial police report that forms the bedrock of police statistics, using this as proxy for crime was problematic, was my feeling having seen all that goes on in police stations, particularly late at night that often has very little to do with any notion of the objective truth.

One way of going a little further seem to me to be look at court proceedings. Now, courts don't determine the absolute truth either, but at least in the process of that you have access to the families on both sides, you have access to the complainant and the accused, you can talk with judges, you can talk to prosecutors, the police. You just have more material to work with. By going through one year of court cases involving sexual assault in Delhi district courts, I found that one-third of all cases that were officially registered as sexual assault were actually consenting relationships between inter-caste and often inter-religious couples against whom their parents had filed charges of kidnapping and sexual assault.

Now if you think about it, this control over young people's lives is not something people who work with India are familiar with. Particularly the control over the independence and sexual agency of young people is not something we should be surprised by, but I don't think we allowed our understanding of those processes to lead us to question statistics the way we should have. What we did have in the aftermath of 2012 was a law that raised the age of consent to sexual activity for young women from 16 to 18, which to mind is exactly the opposite direction considering what we know. Many of these couples were quite young, they were 18 and 19.

What we also had was a legal reform that took away powers of discretion from judges. In cases... in these in term consenting couples, I was finding that judges were essentially saying, "Okay, I can see you two want to be together, you're even married or even have children sometimes by now. I'm going to sentence the man to time already served, and you're now free. That's it, the case is over." That discretion was taken away by the courts, and the minimum sentence is now 10 years. This was seen as a feminist legal reform by framing what judges were doing in the past as anti-women proceedings that involved letting men off the hook. Courts letting men off the hook happens all the time, but I think that was the wrong lens to look at, giving what we know about the statistics. And emphasizes my point about the damaging policy directions that the misreading of data can sometimes take us in.

I do want to make sure that I'm not glive about the fact that... I mean, I don't want to present as if Indian data does a great job of capturing everything. We can talk afterwards about all of the high-frequency data around the Indian economy that India's official statistical architecture is absolutely failing to capture, and the resulting rise of powerful private surveyors and what that means for democracy. But there's also definitional crimes that we are conducting all the time within Indian statistics.

Again, by hanging around with national crime records bureau in 2012 and after, I ended up finding entirely by chance that India follows what's called a principal offense rule in the reporting of crime. What this means is that if somebody breaks into your car, steals your phone and bumps your shoulder on the way out. The FIR will include a section on in the motor vehicle's act, also perhaps theft, and also maybe simple assault because they bump you on the way out. Only the section that carries the highest possible criminal sentence makes it to the official statistics. Ostensibly, this is to prevent double counting and over counting, but what we do have as a result is the undercounting of all crime except murder.

This in itself is not a problem, the [inaudible 00:23:14] and I wrote about it and they said many countries follow this rule, but we never mentioned it anyway in our question statistics. It wasn't an asterisk or in italics, it just didn't exist anywhere the way it does now. The other crime that I love that we commit through definitions has to do with occupations. Anyone working with labor data in India will have this complaint that the world of work has changed so remarkably in the last 20 years in India, and definitional categories have not caught up. So the census, for example, looks at agriculture, home-based work, and all else. Vast, vast suites of the Indian economy are now in this all else.

Another thing that India's official statistics do, we have a national code of occupations, and I found that it had code 121, directors and chief executives. By official data, this is the most common occupation for urban men, directors and CEOs, and the third most common occupation for urban women. This sounds like a very white collar, well-out economy, but of the women workers described as directors and CEOs, 99% were actually self-employed, of which one-third worker unpaid family workers. These were women working unpaid on their husband's vegetable carts and samosa stalls, and being described in the official classification as directors and CEOs. That's when there's data that we don't collect, there's data that we collect and misclassify and just don't fix for years and years.

What I want to do for the end now is to bring together my fourth and fifth points. My fourth point is around the question of, does India manipulate data? Does India lie through data? Can we trust Indian data? Is it all fudge? My fifth point is around the future, which is the collaborative communities that I have seen come together through the pandemic. In a way, the story of COVID mortality brings both of these points together. My broad answer on does India manipulate statistics, is that when that happens, when there are problems with statistics, we still do have pillars of democracy that work and this information comes out. We know when an important survey was delayed, we know when another one was attest. We know about it, it was widely written about in the media, discussed in academia, whistleblowers within the statistical system themselves.

I don't feel like the problem of data suppression and manipulation to be overstated to the point that there is blanket suspicion of everything. Let's be skeptical of data, and there's reason to be skeptical of it. We do have enough oversight mechanisms that tell us when to be skeptical. But the broad blanket suspicion leads people to feel like they can't work with anything, and actually comes in the way of doing better. This doesn't mean that we need to take the eye off making sure that this data remains clean, but I sometimes feel this problem with loose talk ends up being overstated. This particularly was the case during the pandemic.

India's official death toll from COVID by the end of the second wave was 500,000, while the WHO's estimates were five million. When you have a 10x underestimation, that seems like manipulation, right? Without that, how could we have reached this point? I want to try and explain how structural as well as current issues that do not have to do with a very ham-handed notion of how manipulation works, led us to this place and really is the mechanism we need to think of for other areas of numbers as well.

First, why should we think that the numbers were off? Why not just accept that Indian numbers were right? For one, at least in the early parts of the pandemic, India's numbers were so much lower than any other comparable country in the world, that it really didn't make sense. There were questions to ask about why this was the case. Then among Indian states there were inexplicable differences. Why should one Indian state see so much higher numbers than others? There was a lot of time wasted in asking questions about innate immunity, BCG, the whole gamut of, now painful to think about, conversations that we had after the first wave. So I believe we wasted a lot of time between the first and second waves wondering about whether there was something exceptional going on in India or in parts of India, rather than asking the question about whether there was something exceptional going on with Indian data, as I think has been fairly well proved is now the case.

Why were these numbers so off? Well, for one, India has a health architecture that misses deaths from all diseases. We know this, in 2017 for example India's official death count from malaria was 192 deaths, but the IHME's modeled estimates, with all their problems, for the same year was 50,000. That's a 40x underestimation that never made it to any media headlines and never became a international incident the way the COVID numbers became. Diarrhea, tuberculosis, all of these diseases that kill a lot of people in India systematically are undercounted, partly because we haven't understood how people access health. So most of our health data comes from the public sector, but the majority of Indians, including the poor, now access health from the private sector from whom we haven't yet figured out how to get proper data.

These numbers are slightly updated now, but essentially we also went into the pandemic with a registration system that was simply not able to capture all deaths. It's getting better every year, but we still miss some deaths, particularly of people in rural areas, women, and those from marginalized backgrounds, all for reasons that seem obvious. We also have a particularly bad system of medical certification of deaths. India's richest and most developed state of Kerala medically certifies only one out of ever five deaths, even now. We've simply not worked the system out well enough to be able to have a medical certificate certifying cause of death. All of this is pre-pandemic.

Then in the pandemic we had some pandemic-specific issues. For example, we officially followed the WHO's classifications on what should be done to the COVID death. This included both confirmed deaths, we knew that there was a positive test prior to death, as well as suspected where all of the symptoms seem to suggest it was COVID but there wasn't a test prior to death. This was what we officially followed. On the ground, reporting by me and others has shown that not a single Indian state register has seen the suspected death. We just didn't do that at all, we only counted confirmed deaths, so we know we're going to miss some.

Then when the second wave hit, I mean, I think the sheer scale of what happened in India second wave made the dissonance unmissible to anybody who lives anywhere or had connections with India at the time. I think sometimes it's hard to overstate just how devastating that wave was and how it essentially impacted virtually every Indian family I know. It became pretty apparent to people across the board that something was... the numbers were being undercounted and we had to do something. This is where the second part of what I'm talking about, these collaborative communities began to emerge. Here's an extremely low tech end of what I'm talking about. This was a example, an effort from Kerala and it involved nothing more than a Google spreadsheet. These were doctors in Kerala who knew their communities extremely well and could see that there were people in their communities who had died from COVID, who were not making into the official numbers.

People have a Google spreadsheet. They made a list of people who they could see from obituaries and media reports had died of COVID, and on the right-hand column they would say, "Hey, have they made it to the official list?" If they had there would be a check mark, if they hadn't there would be an X. Whenever there was a reconciliation by the state government, they would reconcile the data as well. I believe this actually ended up feeding into accountability mechanisms because the state of Kerala systematically, every few months would do this big reconciliation and add thousands more names to the official planning. As we know now by the end, the underestimation that Kerala did turns out to have been among the smallest. They were reporting very high numbers, but that's probably because they were missing fewer deaths.

Then what began to happen is that journalists, particularly in non-big cities and non-English newsrooms where the risks and the costs are much greater than anything I experienced, began to fan out and try to figure out what was going on in the city. This would sometimes involve going to hospitals or crematoria and pulling out registers that looked like this, going through the lists and comparing them with official numbers. Really ground up hard work that ended up feeding into a broader understanding that ended up going all the way to the WHO. What I and other journalists did was to extend this thinking to pool this data for individual states.

An early one was from the city of Chennai, which uploads all death certificates to its website. What you can do then is just get a count for each day, and this count ended up showing, "Hey, there's a big spike in the second half of 2020." The second wave hadn't hit yet. In the state of Madhya Pradesh, it looks something like this. I mean, I find it very had to believe this number sometimes with a chart that looks like this. I mean, the state of Madhya Pradesh sees 30,000 deaths every May, roughly, just in normal times, it's a big state. It saw 160,000 deaths in the May of 2021. There was no heatwave, there was other big wave of disease. So it's a bit hard to continue having this conversation about where there a lot of excess deaths that happened in May 2021, and you have a chart that looks like this. This is official numbers but not released officially.

Here's the chart for Andhra Pradesh that looks like a differently color-coded version of exactly the same thing, which goes on to show how the second wave ran in the numbers even, exactly as everyone experienced this. This enormous spike over a very short period. I'm not going to get too much into the numbers, but just to show you that color coded-chart, this is the newspaper, the Hindu, which put together... and these numbers have changed subsequently, but comparing officially registered deaths with total excess mortality numbers to look at how much that estimation was.

There's Kerala in the green, which as I mentioned, reported very high numbers in the early days with the pandemic. But perhaps that meant they were just doing a better job of... they were just doing less underestimation, because that underestimation ratio is so small for that. It's also important to always triangulate from other data sources, so this is data that I pulled from India's National Health Mission, which is not the source that this is meant for. But it shows this huge spike in deaths from fever and unknown causes. Again, it points you into one pretty clear direction.

I'm going to end with a couple of thoughts. One is, I am keen to talk to people who live outside India and the international community around what can be done to support these collaborative communities that I have seen emerging in India, particularly in the last couple of years. These are people sometimes with tech skills, sometimes without, but deeply committed to data being made public in a nonpartisan way for everyone to use. I also want to bring in the role of data from big tech companies.

One of the notable omissions in my book is data from any of the big tech companies, not from a lack of asking but from a lack receiving. If there are ways... Here too I believe that there are people working in all of these companies who are committed to some data for good. These are private companies that don't own any of the data. Is there a way we can come together to think of a compact of data for public good that can be brought in to help, not just journalists but also people working in the social sciences so that we aren't trying to build these kind of problematic individual relationships within companies to get their data when we want to write about it, with a inherent almost whiff of quid pro quo when you ask for that data.

I also want to center the question of why the COVID reporting in particular was able to push through some of these bubbles that I talked about in the beginning. One of the more fundamental notions of data is that it is an aggregation of people. Finding ways to bring it back to that notion, to reminding people that data is an aggregation of you all, of y'all lived experienced. That numbers can offer validation per simple to people when they are sometimes deprived of it as they were in the pandemic, is a powerful concept that helps build long-term credibility. Also, helps build buy-in, especially in a context of highly direct disease. To show people what those numbers mean and why they matter is a truly important part of communicating these numbers.

Finally, I want to leave you with this question that I have not... It's really a question for me as well. We are seeing more and more private data sources, these are private institutions that have put in a lot of money to build and create architecture to pull in data for private companies. They are not obliged to give it to any of us for free, this is their own work. But as they grow more and more central to even academic work around India, it's important to try and think of where they fit in our notions of democracy. Then the more people like me and others try to bootstrap our way through Indian data, it makes me wonder about whether that means that then we lower the pressure on democratic bodies to give the data that they are obliged to give.

I mean, I know these things can all happen simultaneously, but where they all fit into the landscape of making governments accountable, but also not stopping work in a data poor context... Not all of India is categorized as data poor, but in individual context, is something I'm interested in thinking about, don't really have answers on but is going to be an important part of how we think about the Indian data landscape going into the future. Thank you for that. I look forward to questions.

Tariq Thachil:

Thank you so much, Rukmini. I think I'll let you field your own questions if you want to. Just raise your hand if you have a question and you can ask it of Rukmini, and then Shakir can also let me know if there are questions from online. Maybe if I can just get us started. Rukmini, one thing, the note that you ended on, especially in terms of what can be done in very privileged spaces like the one that we're all meeting in to help this... or to think through this question that you asked at the end. Something that I've been wondering is, are there real and have you faced in your own discussions with researchers, both in India but perhaps even more in the US and other places, problems of incentives to engage in the kinds of collaboration... Which again, then there's a question of whether that collaboration and bootstrapping is even the right way to go, but let's assume that it's something we want to do.

Because one thing I've been noting just in the production of research and the fields that at least I'm most embedded in, is that there are often perverse incentives that play even among research communities to create fiefdoms of data. In a world in which there's less publicly accessible data in India, sometimes powerful research bodies... I'm not trying to [inaudible 00:39:51] anyone, I'm just saying that powerful research bodies get privileged access with particular governmental... and then can produce a lot of useful studies, but it's unclear that the incentives are to make it accessible. A lot of the drive in our fields is to make data accessible after you publish something, which is often many years after the phenomenon is happening. So I'm just wondering whether you've encountered that, or whether you see that as a problem within academic communities. Is that maybe something that we all then need to think about? I don't know what your thoughts are about that.

Rukmini S:

No, this is absolutely something I deal with. To be honest, it's also a process of unlearning for me, myself, because the instinct of journalists is absolutely to hold information. To try and unlearn that and to try and say, "Please release this data, I also would like to write about it," is... I can't say I've got past that yet. I mean, the temptation still is to do exactly what you're mentioning, which is, "Give it to me. I want to write about it. Then let's make it public." When you see it in the context of academia and particularly, as you mentioned, the long time it takes to put it out, additionally when you see it happening in the biological sciences during the pandemic when this data was made available to individual scientists and researchers, and then available online after everything had gone through peer review and made it. It just seemed unconscionable because this was information about disease pattern that really should have been available to at least local administrations much earlier.

I suppose, just as I am trying to figure out this process of unlearning, I do think it needs to be a broader conversation in academia and among journalists as well. I think if we're going to say that we want to... Being committed to open data means being really committed to open data. It does mean that in any case many of these organizations are so well resourced, that even if the data is made public equally for everyone, they're going to produce the papers first. So there are all of those privileges or advantages that they're beginning with anyway.

I think we're beginning to see pushback against this. During the pandemic there was certainly anger among Indian scientists for a lack of access to scientific data, which was then made available to individual scientists. Usually associated with prestigious like universities. Then saying, "Oh, now I put it on my GitHub," just feels like crumbs. That doesn't feel great at all. I'm all for thinking of ways to create compacts, and this seems like one more of those. I think to that respect, to that end, the SHRUG dataset by Sam Asher and Paul-

Tariq Thachil:

Novosad.

Rukmini S:

... is one great example of there is so much more that you still can do of the development data lab, and then that is equal to look at. It hasn't been released after all of the academic work is over, so perhaps that's closer to a commitment to open data than many others have [inaudible 00:43:11].

Tariq Thachil:

Ashwin.

Ashwin:

Thank you again for a great talk. Could you please reflect on the fact that your work and others in your community of data journalists, it's also emerging at a moment when there is intense data application of Indian reduction across the world, newsrooms in particular. The data application that's happening there in terms of capturing of all levels of granular data is very much a conservative [inaudible 00:43:38] in terms of making assumptions about readership and capturing data, but also in what [inaudible 00:43:43]. How that then shapes editorial decisions and the [inaudible 00:43:47] industries and so on. I'm trying just think through what data journalism as a critical practice means at a moment when they're all thinking very critically about data application as a huge problem globally. I just wanted to ask if you and others in your cohort of data journalists, what kinds of pressures do you feel within newsroom settings? What kinds of conversations are happening about how to push back against a very different order of data application? Could you just reflect a little bit on that?

Rukmini S:

I think in the US this is the second time I've been asked a version of this, and I wonder about why I haven't thought about it with why I don't have a good enough answer. I think one of the reasons is, it's almost a feeling like you have to get to a critical mass of availability of data before you cross the hump into thinking about these, and perhaps even that's... I spend so much of my time focused on needing the data to answer such fundamental things about India, that this sort of reflection is something that's maybe happening now or hasn't really happened until now. Just one context where it... Well, a couple of context where it has come in is, one is of course the data application that journalists encounter of their own profession. This, in a ironic sort of way, it often means that data stories are themselves around the poorest read, and then does it mean? Are you going to rid entirely.

I'm not sure we've figured that out very well yet. It all ends up being very individual editor focused, there are some who are much more focused on these metrics than others. Though I actually do wish that there was better social trends work done around the sort of work that Sutra Rabinathan does around disinformation, even around caste information. Even there's all of the news talk of, "Don't do a scatterplot, nobody understands that, do a bar chart." I mean, as if these are some scientifically established norms. What in journalism or data journalism gets through to people is not something we actually know about, we just make assumptions about no parts better understanding that doesn't come just from page views, which is what we use right now, could get us towards some notions in there.

I think another problem, and this is something we talked about the other day, is that across the world and in India there is now a sense that data journalism is a technology-led profession. So entering it with some tech abilities is more important than any other skill, than even having an econ degree, which in the past would perhaps been the first step that you need. So in newsrooms that aren't doing enough thinking through, this can end up being newsrooms that are... or data teams that are extremely well powered to do cool stuff without a grownup sitting at the table trying to think of what are the big questions we're there trying to answer.

One of the reasons I think COVID work by a whole host of journalists stands out because I don't think data journalism has been in the forefront of trying to answer the big questions about India in the last few years. I can't think of other big questions that we could hear someone's great data reporting answer. Perhaps we could even say that about parts of social science academia, I mean, they know that it's not coming from their reader, and perhaps was one of those cases where everybody did do their jobs. But that's my sort of unformed answer to all of this. Get some students.

Tariq Thachil:

Yeah.

Speaker 4:

First, thank you. It's a second time hearing your talk in one week, but I still learned so much from today. My question will be about gender. I'm curious, you mentioned last time actually, as a woman who is working on data journalism that it is a very... I don't know if I've characterized right, but a usual thing in India right now. So I wonder among your colleagues, what are the current percentage of the female data journalist? Does their work significantly contribute to challenge the data bias in terms of what to look at, where to look at, and how to get data? Also, how to ensure their, say, personal safety and all those kind of issues, because I'm sure there are so many social structures that actually prohibit women from getting data on the ground. If you could speak to that, that would be great.

Rukmini S:

Yeah. Great question. One of the interesting things that's happened in English newsrooms in particular, but also in many non-English newsrooms, is a huge influx of women. Indian newsrooms continue to be extremely upper-caste dominated, but they are now perhaps more gender equal than they've ever been. This still doesn't mean that we have any significant number of women editors. I would be hard-pressed to think of one at the top of... in the newsroom. So that glass ceiling most certainly exists.

Another interesting thing that happened in the last two years, going into the pandemic most newsrooms had women covering health because of the socialization that means that women are assigned what are seen as soft beats which include things like health. You see this even in politics, our health ministers are often women because it's seen like a womanly thing to do. But what that ended up meaning was that the most important path-making, exciting reporting of the last two or three years was being done by women because they were in these positions already. So whether that'll mean some sort of reckoning in Indian newsrooms around what beats women should be given, how fast they can rise, what it means to their future paths to be an editor, I don't know if all of that is going to outlast the pandemic. But that was certainly an important moment there.

At the moment, the cohort of data journalists in India is quite small, but within that, yes some of the top individuals are women. These are sometimes people who come from a design background, which also sometimes is a interesting socialization of what fields women are encouraged to pursue or not. I do wonder what will happen with the growing techification of data journalism, because this means that women and people from marginalized backgrounds are much less likely to have these skills, and what this means for the future of data journalism is something we'll have to see.

In terms of safety, I think across the board women journalists face safety risks, including data journalists. I think isn't enough thinking around Indian newsrooms around how to keep women safe, apart from saying things like, "If you're going out late, you get a car." Or that sort of very one small sliver of how you do it. There's also not enough attention paid to keeping women safe online. This is something that women journalists end up having to navigate entirely by themselves, and leads many of them to burn out entirely. Because if you don't do what I do, which is never read my mentions on any social media ever, it's a lot and it leads some women to be pushed out of the profession entirely.

Speaker 5:

Thanks for this presentation, Rukmini. You started your presentation with the image of Nehru and Mahalanobis and the structure that they set up. I'm just wondering if you can give us your thoughts on [inaudible 00:52:19] of the current [inaudible 00:52:21] who actually upholding the values that was set out, with respect to data collection in India, given what we've seen. I'm also wondering... I mean, I don't know if you have any thoughts on this, but the reports that were being suppressed and also the kind of data that was coming out from the government with respect to COVID, has that in any way perfected how the outside... or internationally Indian data is viewed vis-à-vis with Europe. Yeah.

Rukmini S:

Great. Thank you. Yes, they're both related so I can take them together. I'm keen to think about structures, because structures can outlast individual governments. One of the reasons I pulled up that picture of Nehru and Mahalanobis is to think about what were the structures that were put in place, and what have they meant in terms of still having good data, and what was not put in place and we perhaps need some work now. The sample surveys that Mahalanobis pioneered and Nehru supported means that we have this huge body of comparable research over time. But I don't think that we've done enough work on thinking about independent, autonomous oversight mechanisms, so of the office of national statistics a new game variety which are truly autonomous. I think not having a national statistical commission that could do anything worthwhile in stopping the delay and then suppression of two NSS reports, is a good indication of the cracks in house that Nehru and Mahalanobis built, and the stuff that needs to be fixed. That's certainly a place that we wait right now.

Another thing I often think of is the spirit of innovation that drove some [inaudible 00:54:15] there. There's a story about how when government was trying to figure out crops... sorry, plot sized and crop yields, and whatever our presidency did was essentially, there was this argument there about sample surveys at all, "Is it a good thing, does it work? It's just a sample, how would it work?" So they an open competition. Their own state department did plot by plot census and that the team from iron side did a survey, and the survey came closer to the real numbers. So that made a great on-the-ground case for sample surveys. This spirit of innovation which we could easily do in smaller pilots is not something that I think enough is happening right. It is something that this government could do well as well.

After the suppressed NSS report on consumption, the government has said that it's changed its methodology to some extent, and there's a new one that should be out, in fact it began in July. On that count, I do like to... the international community sometimes behaves... We should all criticize the fact that that report was suppressed. But let's not believe as if India never going to produce any numbers on consumption every again, and the poverty estimation project is dead in the water. There's no reason to go that far. There is a new report in process. When it comes out, let's argue about the methodology and perhaps we'll feel that it wasn't the right one. But I don't think we need to despair so heavily of it as well.

Around when that methodology was changed, why didn't we have an open pilot where we tried out like six types of how to estimate consumption? Why is it that the same criticism of national account statistics has gone virtually unanswered for decades now and then has become sort of argument of the right, because not enough on the left engage with it. I do feel like that spirit of innovation has not really taken up at all in the last few years. We also struggle for not having a well trained enough committed cadre, so part-time enumerators which is increasingly something we've seen also damages the original architecture.

I think it is good that the international community made a loud noise about the access of consumption data, as well as problems with the COVID data. It also ends up strengthening people within India who are doing this work when you feel like there is international support. But I don't think there's grounds for people to give up, it just means that we do now very specific area that we need to be paying better attention to. I think it's unfortunate that the international criticism was taken so poorly within India, because then it set up an adversarial tone that didn't necessarily need to be it. I mean, everyone on both sides of that argument is just committed to more and better data.

Tariq Thachil:

Let's get a couple of questions from undergrads. I see one at the back. Asha, go ahead.

Asha:

My question's about [inaudible 00:57:29]. Especially we've seen recently zap words was like Allah and COVID, that recently they tried implementing. But obviously the criticisms that I hear is [inaudible 00:57:39] but that's our data collection. But at some level [inaudible 00:57:45] data that's [inaudible 00:57:47] offline. So what do you think is a good trade-off between come into action, try to stay especially [inaudible 00:57:52]?

Rukmini S:

Such a great question. Essentially, I am at the place where you and your question are, which is, I see these two sides and I'm not sure how it's going to go. I felt this very strongly during the pandemic as well, which is when we had one dataset that had to do with COVID tests, another entirely to do with hospitalizations, and a third on health outcomes. All of our understanding around things like vaccine effectiveness has come from the UK, because they used the vaccines for some time. But it's also because they had... The NSH ID allows you to aggregate all these three and then say, "The person has had a test, you can track what their outcome is." Of course, it's anonymized and protected and which is why it's valuable information, and so we need to have that essential conversation about privacy just for the earlier reason that you mentioned as well, which is an even more dangerous one since it has to do with voter rights.

But I don't think that we can not have this conversation either. I do think that I've brought this up, for example, there's so much push back against the notion of say that universal health idea that the government was talking about. Some of it is around questions of privacy, but some of it is also reflexively, "You shouldn't be counting more people, we shouldn't be doing more of this. Why do we need more IDs?" This is one more example where I feel like the two sides need to be talking to each other much more, and I really am on the side of more integration of some of these things. We cannot answer such fundamental things. State governments cannot direct schemes properly, because they do not have integration between datasets for different benefits. So they can't figure out who's being left out of what. Hey, I'm in a lucky place of not having to come up with actual solutions, so I can say that I see both sides of this, but it needs fixing. Yeah.

Tariq Thachil:

Any other student questions then we take a couple round? Any other student questions?

Speaker 4:

I wanted to ask, Rukmini, particularly you began talking about qual and quant data, and how you put the two together for thinking about COVID and doctors from Kerala as an example. Obviously that's really painstaking work emitted by scale. I'm curious if you have seen on your or other examples where the qual really speaks to the quant, either at a larger scale or outside of certain emergency of [inaudible 01:00:36].

Rukmini S:

Yeah. I think the way that this is largely happening is through machine learning around techs, some with better results and some with worse results. I think one of the very promising directions for this is around judicial data which is so... I mean, a complete black box in India, for the very basic reason that every court case is designated to an entirely different classification system across Indian states. It's been virtually impossible to compare judicial outcomes as well as... data make it to courts between Indian states. This has meant that machine learning led initiatives like people like the CivicDataLab, Duchs, Algami, others, most of them based out of Bangalore, are leading to very promising directions where I hope in the not-so-distant future we're going to be able to answer questions very simply.

Basic questions about India like what is in the docket of the current judges? Who is more likely to convict? Data algorithms that are actually like algorithms now in the US, because they're able to quantify it so well. This is really essential stuff about India that we've not been able to answer so far. I think just a large number of people dedicating tech and time to this for 15 years quietly, has led to a place now where I feel like we're going to have some movement on this in the next couple of years. I think fields in which there are also incentives well aligned for the private sector allow tech adoption that then others can take a hold of. So lawyers need to know about [inaudible 01:02:24]. So private sector pretty much solved this problem a long time ago, for paid databases, and I think that's helped tech adoption for people who read the public good as well. That's what [inaudible 01:02:37].

Tariq Thachil:

Okay. Let's take two at a time. So go ahead.

Speaker 8:

My question is around the area of call it democratic backsliding. There's a lot of data on that, the Freedom House, the read democracy. But I think this is data something where you can test it. If you had to convince a non-academic, or I mean, that how do you say that India's democracy is kind of eroding. What kind of data would be useful to take that?

Tariq Thachil:

Let's also take Akura's question, and you can answer them jointly. Akura.

Akura:

I was wondering, and maybe this is less about data but access. If you had any clearance at all perhaps you think the right to inclusion... I mean, to get data that exists, but also to figure out why if something has not been released or if it doesn't even exist, why is it that it's gone missing or it hasn't been collected or correlated. Is there anything you can tell us about it? I know it's been weakening over the last nine years, but have you been surprised, has it worked for you ever at all, any such information?

Rukmini S:

Okay. I think most of these indexes need better work on the individual components of it. This applies to democracy, this also applies to advances around wealth development, hunger, any of that. I think when you do a slightly clumsy job of composing the index, it's so much easier to batt away that that's backsliding. You actually set the conversation back when it's not a great index. This is always going to be hard and I think I feel for international agencies because it's going to differ so much within individual context. For example, if you wanted to use communal violence as an indicator in India, we know that the official police data on communal violence is in such bad shape that you're not going to get good outcomes from it. No, I don't have a solution for it, but i do have a... I mean, I think reporting on indexes is quite hard and it needs much more work looking at individual indicators, because sometimes it just ends up being counterproductive in a way.

I haven't had enough use of using that yet for data. Perhaps I should do more a bit. I think one of the good examples of it has been, again, some of it and this was during the pandemic for city administration. Sometimes it works best from municipal corporations who essentially have this data but have not put it on their website. If I'm reporting on national data it's extremely unlikely the datas that's not already available either on the government website or by my contacting someone in the government and asking it, would be made available throughout the year.

What does happen is as you say, a good paper trail for where is this and why has it not been reached? Just as I find parliament questions an extremely useful [inaudible 01:05:55]. It's not that data that everybody is seeking will be put out in parliament question, but that explanation of, "We haven't collected it because..." is valuable as well. But from a long-term data access point of view, it's less satisfying. It provides that one headline that, "Government said X doesn't exist because of..." But haven't yet seen it as a source of data that's not otherwise available. Though I think using it for individual administrations is perhaps a promising way to use it.

Tariq Thachil:

Maybe we'll take the final set.

Shikhar:

I'll read out two questions. First one is from Abhishek Mor. He asked, "What is your opinion about the quality of National Family Health Survey, NFHS, data since it is used widely by governments, policy makers, and researchers. There's some skepticism about anemia data of NFHS with research cycle since it is showing quite sharp increase." The second one is from Sanjay Mishra, and he asked, "Some observations during pandemic and otherwise indicated that data collection tracking and interpretation were hugely influenced by the rhetorics of electro-politics, thus impacting good quality root cause analysis and fixing issues. What are your thoughts?"

Rukmini S:

Okay. One of the great parts of... Broadly I think NFHS data is good, it follows international conventions because it is within the BHS, which is think is actually an important way to think about data and meaning or having it follow broad international conventions. Yes, I think when people look more closely, particularly at more granular NFHS data, there are often fluctuations that are inexplicable. Two members of Tamil Nadu's planning commission, for example, wrote about how there were inexplicable fluctuations in the most recent NFHS, and it wasn't a case of, "This data is making us look worse than we are," which often is governments respond. It actually was... this is not making sense.

In one case this data is making us look better than makes sense because the pandemic would have ended up in these schemes, so I think that was a valuable intervention also because this sort of criticism should come from the state government sources who understand much better the context in which this data is being reports. So I do think we need to look more closely at it. Another inexplicable area, to me, often in NFHS data has been around the sex ratio, both at birth and [inaudible 01:08:51] which doesn't in some ways correspond with some broad trends in the Indian demography. Yes, I mean, let's ask questions. It doesn't lead me to feel there's some wholesale issue [inaudible 01:09:04], but sure, there are some unexplained fluctuations.

Tariq Thachil:

There's been this dramatic improvement in the sex ratio [inaudible 01:09:05]-

Rukmini S:

In some places, and dramatic decline in... Kerala for example, the sex ratio at birth as per the new NFHS is lower than Punjab and Haryana. [inaudible 01:09:20] really embarked upon something massive that went on in the state, and that maybe it did, but it doesn't seem in line with other things that we know. So it needs more looking at, particularly at the state level.

The role of current politic... It's one of those things that because it's unquantifiable, I'm not very sure what to make of it. There was some argument that some release or some data was held back before this election or that election. I think in way, I mean, if the implication is that elections can be swung by data releases, then wonderful, that means we were doing such a great job.

Tariq Thachil:

We're all in the same [inaudible 01:10:04].

Rukmini S:

We've done such a great job, the data journalism swings outcomes. I mean, I know this is a more serious question than that. I don't think that this is something quantifiable, but yes, the cherry picking of data and it's presentation for electoral purposes is undeniable, happens as per suspected. Is a very important part of how data on religion, in particular, is reported. It's a very important part of why we are having this entirely demographically, idiotic conversation around the control of family sizes, which is actually the opposite of the problem we have been to be thinking about right now. It is clear that it is driven by the instrumental anti-Muslim sentiment, so it's important to call out when that happens as well and not pretend as if data is happening in this apolitical vacuum. Yeah.

Tariq Thachil:

Final question and then we will wrap up.

Asha:

I just want to know if you've experienced this problem, when you spoke [inaudible 01:11:24] statistics where a point is targeting, it uses targets. Have you seen something similar happening with other Indian and [inaudible 01:11:29] datasets, specifically the HMIS because it targets something that state governments are monitoring to check the local policy to see that it stops measuring whatever they're supposed to measure and becomes a way... NFHS maybe be reflecting some of it. Like HMIS doesn't.

Ashwin:

[inaudible 01:11:48].

Asha:

Oh, sorry. Health management information system.

Tariq Thachil:

Let's also get this question in and then you answer both of them at once.

Rukmini S:

Yeah. I haven't actually seen this happen. I mean, it's not that it doesn't happen but it's not something I know of.

Tariq Thachil:

Go ahead.

Speaker 10:

What is, in your sense, the prevalence of motivated reasoning amongst Indian consumers of data? I would imagine data journalism has an impact when people don't engage in motivated reasoning. Is there something that data journalism can if that is a problem [inaudible 01:12:28]?

Tariq Thachil:

You want to just explain what motivated reasoning is?

Speaker 10:

Sorry. Motivated reasoning just means people fixing the conclusion and retrofitting information to that, and essentially not updating their beliefs based on new information because they... "I think Party A does great work so the data must look that Party A does great work, and then everything else." Okay. sorry.

Rukmini S:

No, that's a great question and in a way also brings out the point that Ashwin mentioned at the start, because my answer is that I feel like they're not doing enough measuring of this. It also, again, reminds me of Sutra Rabinathan's null finding paper and how to think about broad information and motivated reasoning around it. One example to me of this is the reporting... Let's talk about 2019 when there was extremely high unemployment, and there was also media reporting around unemployment. One of the things that I've seen through opinion polling, political opinion polling, for example, was that people said before the 2019 election that unemployment was an important issue to them. However, this did not mean that these were people who then voted out the incumbent. In a way I feel the data journalism around the opinion polling does a disservice to all of our understanding about Indian voters.

Let's start from the problem that the opinion polling does a disservice by still asking questions about, "List what is the most important issue," and then taking it at face value. Which allows for things like, "Unemployment matters most," and then the incumbent is reelected despite not having a [inaudible 01:14:10] on employment. I don't think we have enough... I don't do any research around whether journalism changes minds in India and whether data can have a role in this. I do find anecdotally that people who do not hold the political positions that are being supported by worker journalism is picking out, other ones who typically push back or call it into question. That does seem to indicate that data journalism do consume along extremely partisan lines. All of which only makes me feel, what do we need to do to push back this? Because what is the point of going on talking, going on preaching to the choir as is happening across the board in Indian journalism.

That is where I try to take some lessons from the COVID reporting, because that is actually one example of having broken through the typical bubbles. For example, that first chart, the Madhya Pradesh one, ran on the front page of the Dainik Bhaskar. It would not have been typically seen as the first home for anti-establishment reporting, but first of all, Dainik Bhaskar have a lot of excellent reporting during the pandemic, all of the gun riot reporting was led by them. But I also think two, three things happened. One is, it was unmissible. The media incentives were such that it was unconscionable not to talk about it, and perhaps that also allowed for the consumption of it. When you see it all around you and it's reflected in the numbers, then even if the party you support is not saying that, it becomes hard to disbelieve that.

Additionally, I do feel that data that ultimately allows dignity to people who have robbed of their dignity in other ways is sort of accepted in a way, and people reach out to us after this to say exactly this, that they felt that their loved ones were being left out of the numbers and that this sort of reporting in some ways restored dignity toward what we have gone through. Maybe thinking of that as a broad principle on which to think about journalism that can break through motivated reasoning, maybe that would help in newsrooms.