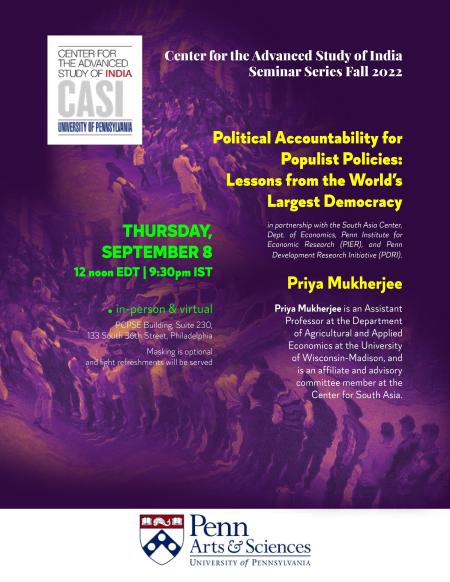

Political Accountability for Populist Policies: Lessons from the World’s Largest Democracy

Center for the Advanced Study of India

Ronald O. Perelman Center for Political Science & Economics

133 South 36th Street, Suite 230

Philadelphia PA 19104-6215

(English captions & Hindi subtitles available)

About the Seminar:

We know little about the electoral effects of policies with broad appeal that are implemented by popular leaders, but which have adverse economics effects. In this seminar, Dr. Mukherjee analyzes voter behavior following one such policy implemented in the world’s largest democracy — India’s 2016 "Demonetization" which unexpectedly made 86 percent of the currency-in-circulation redundant overnight, and led to severe cash shortages and economic hardship in subsequent months. Yet, the policy appealed to a majority of voters and was framed as one that would combat corruption. She leverages a discontinuity in the number of bank branches arising from a nationwide, district-level bank expansion policy. Using the fact that districts with fewer banks had greater cash shortages, she identifies the impacts of demonetization’s economic severity at the bank-expansion cutoff. Regression discontinuity estimates show that following demonetization, voters in places with more severe demonetization had less favorable views of the policy. Using a difference-in-discontinuity design, she finds that the ruling party performed relatively worse in regions with more severe demonetization, receiving a 4.7 percentage point lower fraction of votes, and were relatively less likely to win seats in state legislatures. Areas that were historically strongly aligned with the ruling party were nearly unresponsive in voting behavior, despite having a less favorable view of the policy itself.

About the Speaker: Priya Mukherjee is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and is an affiliate and advisory committee member at the Center for South Asia. Dr. Mukherjee’s primary research interests are in development economics, with an emphasis on human capital and political economy. She utilizes both field experiments and non-experimental methods in her work, and her current research projects are based in India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Nepal. She earned a B.A. (honors) in mathematics from Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi University (India), an MSc in economics from the London School of Economics (London, UK), and a Ph.D. in economics from Cornell University (Ithaca, NY). She was previously an Assistant Professor at William & Mary (Williamsburg, VA), and a Visiting Scholar at Boston University's Institute for Economic Development.

Priya Mukherjee is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and is an affiliate and advisory committee member at the Center for South Asia. Dr. Mukherjee’s primary research interests are in development economics, with an emphasis on human capital and political economy. She utilizes both field experiments and non-experimental methods in her work, and her current research projects are based in India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Nepal. She earned a B.A. (honors) in mathematics from Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi University (India), an MSc in economics from the London School of Economics (London, UK), and a Ph.D. in economics from Cornell University (Ithaca, NY). She was previously an Assistant Professor at William & Mary (Williamsburg, VA), and a Visiting Scholar at Boston University's Institute for Economic Development.

FULL PAPER

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Tariq Thachil:

Welcome. Just wanted to, before I hand it over to Sarath to introduce our speaker. I just wanted to welcome you all for coming. Thank you all for coming. Welcome to CASI. I know all of you so I'm not going to introduce myself, but well maybe for online. I'm Tariq Thachil the director of CASI and we're delighted to be able to do some stuff in person after long absence of in-person events and mostly doing stuff virtually, which we have now retained. But it's just great to see people actually using this table for purposes other than me taking a nap. Thank you all again for coming. I just wanted to highlight that we have three new posts docs here at CASI this year. New members of the CASI community, Amrita Kurian. I don't know if you guys can see her. There she is. She's waving.

Amrita Kurian is a anthropologist who's come joined us from UCSD, and she works on a number of topics relating to Agrarian social relations. Sarath Pillai is a historian who joined us from Chicago and works on the history of Indian federalism and many other topics relatedly. Shikhar Singh over there who's staring at his marble tea is a political scientist who's joined us from Yale and works on questions of distributive politics and now on India, small towns. So just delighted to have them all join our community and they especially Sarath and Amrita are really curating this series, so thanks to them for all their organizational work. I'll turn it over to Sarath to introduce Priya our speaker.

Sarath Pillai:

Well thank you Tariq for that. The speaker for today is Priya Mukherjee and we are extremely delighted to be able to host her here. Today's talk is held in partnership with four other units on campus. They are the Department of Economics, Penn Institute for Economic Research and Penn Development Research Initiative and the South Asia Center. We are extremely grateful to all of them for cosponsoring this talk. Priya Mukherjee is an assistant professor at the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at the University of Wisconsin Madison.

She's basically a development economist with a focus on human capital and political economy. She's an accomplished author and academic who's published many research papers including in journals like the Review of Economics and Statistics, Economtrica and the Journal of Development Economics. In fact, I actually recommend you visit her personal website where you'll find a lot of her current projects as well as previous published papers. She also taught at the College of William and Mary before joining Wisconsin. Today she'll be speaking to us about a very important topic which is how do people behave electorally or react electorally even in the face of economic policies that don't make any sense seemingly.

The title of her talk is Political Accountability for Populist Policies, Lessons from the World's Largest Democracy. Before I hand over to Priya, just a word about the law and order situation in the room. She'll speak for about 30 to 35 minutes and she's also happy to be interrupted while she speaks and take question, which she will do herself. There will be a Q&A which I'll moderate after the talk. If you're online, the recommended way to ask question is by typing it in the chat box along with your name and affiliation and my colleague Amridha will read out. Over to you.

Priya Mukherjee:

Okay thank you so much for inviting me. This is my first visit. I'm really happy to be here. It's great to be here at CASI and I believe this is your first in-person seminar, so that's really exciting. It's my second in-person seminar since 2020, so it's exciting for me as well. Really happy to present this joint work with joint work with Gaurav Khanna who's my really great co-author at UCSD. As the title maybe doesn't completely suggest or maybe does suggest, and as Sarath mentioned we're looking at how voters respond to a specific type of policy that was implemented in India in particular. This is India's Demonetization and we're going to look at the electoral effects of this. I'll get started right away. Okay, so these are just some of the newspaper headlines that came out right after the Demonetization, and I will, for those of you in the room that maybe don't remember or aren't completely familiar, but I'm guessing most of you did hear of this. This was something that happened in November of 2016. Demonetization was suddenly announced by the PM and essentially it was something... it was a very sudden announcement, unexpected that was announced on TV which invalidated 86% of currency in circulation in the country, and a country where most economic transaction, at least at that point in time were done in cash.

Speaker 5:

So Priya that's 86% of the value of currency or of the number of currency numbers?

Priya Mukherjee:

The value. Yeah. Actually I should say yeah, 86% of value of currency and I forget what fraction of economic transactions, but a really, really large fraction. Yeah. Essentially what happened was that 500 and 1000 rupee notes were invalidated essentially overnight. There was issuance of new 500 2,000 rupee note in exchange for these older currency notes and one could draw up to 4,000 per person per day at that time, although there were some changes in these rules that were announced throughout the next several weeks. There's a paper where [inaudible 00:06:05] managing co-authors where they didn't information RCT in one part of India where in their appendix they really lay out all of the changes in the rules that occurred.

The takeaway being that this was a fairly confusing time in addition to the fact that depositing and getting cash out was really challenging soon after this happened. And you were supposed to deposit notes by the end of the year. What was the goal of this? Now I should say that this type of demonetization or just demonetization general is not something that's that uncommon. So, for example, in the EU when countries transitioned into the Euro, some sort of demonetization happened, especially when you're bringing in different types of bills. What was unique about this was it's sudden and drastic the way it was implemented. What could've been the goal of this.

This is a government stated goal and in the TV announcement that happened that evening, this was stated not just that evening but also in the subsequent weeks that this was done to curtail the shadow economy, fight terrorism, tackle counterfeit currency. As I will show you, a lot of voters likely could agree with this. There was actually broad support for this policy despite all of the negative impacts that happened immediately after. For instance, as one might expect the stock market crashed the next day, GDP growth projections were lower. This is just a photo from all of the newspapers where this is a really large market in Delhi called [inaudible 00:07:44] you can see lines. This was the story in most parts of the country where there were bank branches to make lines outside of places where you have less access to bank branches that's even more challenging.

There were lots of academics or [inaudible 00:08:01] used to be the Chief Economic Advisor, people like him and others that anticipated that this would lead to huge economic costs. Our focus in this paper is on the electoral consequences, and I'll talk about how we get at the causal effects and how we look at electoral consequences. But I will also give you a sense of what the immediate economic impacts were. That's not a focus of this paper, but there have been other papers and we also look into that a little bit before getting into the electoral consequences. Anecdotally what was happening if you were just following politics and the... for example in 2017 if you're looking at state elections that were taking place, the BJP, which is the government's, the prime minister's party was doing fairly well.

If you just look at for example, the states between 2014 and 2017, there's two different snapshots. You can see the number of states just switching from being ruled by other parties to being ruled by BJP's coalition. Without objectively collecting data and really looking into this carefully, you might think that maybe this actually, this particular policy maybe helped the BJP. Well I'll show you soon what we find. But this was some of the stuff that people were saying. For example, the Gujarat Chief Minister said elections for the gram panchayats were held immunity after demonetization. 80% of the gram panchayats were won by the BJP. Thereafter elections were held Maharashtra where BJP won. Congress was swept away clearly shows that Congress does not enjoy people's support on the issue of demonetization.

So despite negative economic consequences, the policy was actually popular. In addition to the anecdotes, we looked at data from a survey run by CSDS in Delhi called the Mood of the Nation Survey. This is a survey that we do use in our analysis as well. The survey was conducted in May, 2017 and respondents [inaudible 00:10:14] from nationally representative dataset, we asked what they thought of the monetization. In that data percent felt that it was a bad policy, 45% thought it was a good policy and 32% it was a good policy that could have been implemented better. There was broad appeal and why there might be this broad appeal, one can think of different things. It could be a combination of the policies moral appeal tackling counterfeit money going after terrorism and on. Also there was quite a bit of strong messaging undertaken by a broadly popular prime minister.

And indeed, like I'd mentioned, the policy was framed as one that will corruption and black money, which turns out were popular concerns of the electorate. What's happening on the economic side though Central Bank has shown [inaudible 00:11:13] has a paper on this that such objectives tackling of black money and moving away from just using cash, these objectives were not actually met? Instead what happened was soon after the policy led to severe shortages and access to cash and negative economic effects. Okay, so what does our paper try to get at? We tried to see using the methods that I'll describe very soon was to see if the prime minister's party was actually hurt in regions that had more severe demonetization. We're going to use variation in severity of demonetization to see if places this with more severe demonetization reacted differently. How do we define that?

We're going to specifically look at regions with fewer banks. We're claiming that regions with fewer access to banks were more adversely affected because the access to cash was even more curtailed in those places. In such places did the voters punish the party that implement the policy? And are there other factors that banner support for the policy despite it hurting economically? So specifically what do we do? How do we get this variation in severity of demonetization? We leverage a policy experiment. We're really going to get a causal effects of demonetization by using this variation. You go back in history and we find that in 2005, and we're not the first to use this, there's another paper that had used it to look at different research questions. The opposition party of the congress had implemented a policy several more than a decade earlier that increased access to banking facilities and therefore cash as well by encouraging private sector banks and generally banks to enter certain types of districts.

In particular, there was some quasi random variation in particular. There was a discontinuity that was used. I'll get into the details of this a little bit, but essentially districts whose number of banks per person was less than the national average got more banks and other districts did not. Okay, so I'll... describing it very briefly, districts on one side of that threshold should arguably be similar to districts on the other side of the threshold, at least back when this policy was implemented. If we compare those two kinds of districts, they're likely very similar on average and that the control and treatment approach that we're taking. We're going to use an RV design and actually we're going use a difference in this community design, which I'll describe in just a moment.

Speaker 5:

Were part of the banks encouraged generally or were they particularly encouraged in areas of that lower banking?

Priya Mukherjee:

Only in areas that had lower bank. They changed the policies and rules. There was lots of red tape in them entering. In districts that were just below the threshold, I mean actually all districts below the threshold banks have access for entry. Okay, so before going the details of how we do what we do, I'll give you a preview of the findings. After demonetization the implementing policy, the prime ministers party in more severe or less bank regions with more severe demonetization his party did have lower vote share. The BJP was hurt in those places. We also show along the way that those places had worse economic up outcomes even though that's not a focus of our paper, there's other work on this. In those places with more severe demonetization there was less support for the policy. There's electoral effects and we see significant heterogeneous effects.

There were some places that were completely unresponsive even though they were economically hurt, they did not vote any less for the BJP. Okay. What kinds of places are these? These are political stronghold or basically places that have had support for BJP in the past, and I'll tell you how we define stronghold. But essentially places that have historically had support for BJP they were actually muted or no impacts in electorally as a result of more severe monetization. These are essentially places where voters are more aligned on just the policy bundle that this party has. The possible explanation we can directly test for this is that there's issue bundling in context like this in democracies where you're voting for just a party rather than for a particular policy, you're going to vote for the party in any case. That's our guess, that's likely what's happening here. We look at other things like incumbency. Voting for incumbent or whether effects on turnout and we don't see anything there.

Given that this is a slightly shorter presentation, I won't spend much time on the electoral chart here, so I'll likely to skip it. In any case, this was not an exhaustive list of all of the relevant literature. But there is a really large literature I guess, or growing on how voters respond to different kinds of fiscal policy, populous policy. We're framing this as a populist policy in the sense it was popular whereas it was not really... where it actually hurt, materially hurt our voters. There's some growing work on this in economics and there's likely more in political science and other disciplines as well. I'll jump straight into the empirical strategy. As an economist getting at the causal effect using data is sort of a key. It's really important. In general what we want to do is have quasi random or plausibly exogenous variation in this variable, which is exposure to demonetization or severity of demonetization and see the effect of that on water behavior.

This is not the specification we have, this is just a toy model of what we would like to get at. That's what we need a exogenous variation in. The way we get at that, like I had mentioned is we look at variation and access to banks, cash or ATMs. And we're leveraging this banking reform that the congress the opposition party had implemented several years ago that made bank branch licensing much easier in underbanked district. What is an underbanked district? The district where the branches per person is less than the national average. It's a sharp discontinuity. And so we use that, but in addition because since 2005 maybe these two types of districts might have evolved in different ways, we additionally wanted to do a pre-post difference. We have data on elections before demonetization, after demonetization on both types of districts. Differences across districts and also difference out any preexisting differences. That's what I'm calling a difference in discontinuity. Yeah?

Speaker X:

Just clarify, you have districts where there are fewer banks and then you have the national average and the districts that are more banks. And it's districts that have fewer than the national average got the policies for bank expansion. It's actually what's on the other side of this continuity that are districts with fewer banks. Is that it?

Priya Mukherjee:

Exactly. That's a great question because when I show you the graphs and the regressions it can be a little bit confusing, that's exactly right. So we're going to use difference in this continuity and the same banking reform has been looked at in this paper by Young user in thesis at BU and he found some economic effects. Yes.

Speaker X:

Could you just speak to the importance of banks as a way of disseminating cash in lower areas? Because for example in [inaudible 00:19:36] sometimes they use individuals who carry cash to religions to disperse against an [inaudible 00:19:43] authentication rather than people meeting at a focal point like a bank to do this. Was it an important way of disseminating cash to begin with?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, so I don't recall exact numbers of this, but it is the primary way, especially if you want to deposit old currency notes and then withdraw that type of transaction, you really need a bank branch. I mean there is to some extent you could do this in maybe in post offices, but banks were really key. Yeah, that's why we feel relatively convinced.

Speaker X:

And there no discontinuity post office coverage-

Priya Mukherjee:

No, yeah.

Speaker X:

... in the design?

Priya Mukherjee:

... this was just purely... Exactly, exactly. Nothing else should be different around the threshold.

Speaker X:

And I know you looked at this in paper just to remind everyone. Did you find good compliance with this in terms of was it that there was also some kind of favoritism appeared where the licenses were granted or some other factors that determined the distribution where the banks came up?

Priya Mukherjee:

So that's a really good question and I do have a few slides which I will likely go over. I won't spend too much time, but that's a really important point. Did this policy actually have bite? Was there good enforcement? It was very good enforcement. Not only were there effects like banks coming in right after 2005, there was growth over time and in 2016 there's a significant discontinuity still. In terms of favoritism, we did not specifically look at that. But what we see is compliance is very, very high and the favoritism would've been around Congress likely because Congress was the party implementing it. That's how we prefer the difference in discontinuity.

Speaker X:

Totally. I think it may just be helpful to know... because you look at just compliance with the rule, but whether there's any other basis where you could maintain compliance with the population threshold but still have some other dimension that determining just what the implication... Just even having a note on that. You may not be able to have data on that, but I think it would be nice to know.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, that would be really interesting. They use the intent to treat in any case, so-

Speaker X:

And yeah so just the working [inaudible 00:21:47] from state or nationally?

Priya Mukherjee:

State. We look at national as well. If I have time to talk about, there's issues with national, with matching parliament [inaudible 00:21:56] and then we're less power, so with less power we find the price a little bit more easy. Yeah, that's a good question.

Speaker 7:

So in practice, does this mean that the places that we're initially underbanked then come to look like the ones that were not underbanked by the time? So does this essentially mean that across India things are relatively even or that they just haven't began?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, so the ones that got the banks, they got significantly more by the time we look at them. Yeah [inaudible 00:22:25].

Speaker 7:

Okay, so [inaudible 00:22:27] so it's flipped by [inaudible 00:22:29].

Priya Mukherjee:

It's flipped. It's totally flipped.

Speaker X:

They become overbanked by national standards.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yes, by national standards.

Speaker X:

By national standards, yeah.

Speaker 5:

So would we expect there to be more use of currency if there are more banks or if there are less banks?

Priya Mukherjee:

So the thing that using here that it's more banks, they're able to deposit the old currency notes and take out the new currency notes. It's right after demonetization happened the ease of transitioning was just better for people that had... In general in terms of transactions later, you know that's the question mark, it depends on how many people are switching to more digital payments, which is also something that [inaudible 00:23:16] later on, but is very [inaudible 00:23:18].

Speaker 5:

But it might be in underbanked areas currency per capita once you control [inaudible 00:23:24] you couldn't use the banking system.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah there might have been some differences. That's right. Because this paper did find some differences around the threshold, which is why we really rely on the difference in this community. Yeah.

Speaker X:

So did you have a sense of the LICO market because they were allowed to accept old currency notes during this interim period?

Priya Mukherjee:

No.

Speaker X:

They could be a set of people who were allowed to accept currency in old denomination, so the exposure LICO markets is asymmetric than maybe of [inaudible 00:23:59].

Priya Mukherjee:

Okay. Yeah, I do not have data on that and that's not something [inaudible 00:24:11]. Okay, yeah, maybe that's something that might be going on, although not... Yeah. We still believe our estimates and all that, but that's an interesting point. I had not heard of that. I won't, again, spend too much time on data. I would say that we have banking data that's publicly available. The list of district there is a memo essentially that has the list of districts that were supposed to get more banks and that's the data that we actually use. Then we use this other data to look at the first stage, did the policy actually have bite and so on. Then we have election data also publicly available.

We create variables on coalitions and things like this. We have data on nightlights of the months around demonetization. Then this survey is really nice. It's called the Mode of the Nation. It's from May, 2017 where they are specific questions about support from all the economics conditions, banking access. The important one for us is actual views on demonetization. You have a question? Okay, so this is the question that was asked, what does the first stage look like? So places that had... so if everything's normalized to zero, that's basically the threshold. You don't have banks so you are far more likely to get more... or to be assigned to be considered an unbanked district. This is based on the actual list that was in the memo. Then we look at other things as well.

For example around the cutoff, again this is the same thing. This the table format is showing that you're considered unbanked if indeed you're below the average. Then we look at actual new branches like growth and branches and those were all significantly higher. We have more in the paper now, it's... The paper is currently under revision so we've added even more things for our referees showing that yes, the policy had bite all the way to 2016. Then we go further to show that the banking policy actually did increase access to banks. I won't spend much time on this, but essentially this is just showing that places on left of threshold had a lot more growth than branches relative to places just on the other side of the threshold. Number of accounts, credit limit, everything was significantly different.

Similarly, we also wanted to see how it looks in the CSDS data, which is the voter survey. They were asked questions also about having a bank account or post office account or debit or credit card. It's possible that between demonetization and May, 2017 they got some of these things because they were more badly affected. It's possible this is a combined effect, but this one also shows that around the [inaudible 00:27:02] there are significant differences in the survey data as well. That's all sort of preliminary before I want to show you before getting to the electoral effects. But along the way we did do some more work just to check a few things. For example the Congress, the other party was the one that did the banking expansion policy.

Were there any electoral effects of that? My prior was that probably not, because when a private bank comes in it's not salient to the voter's mind that, oh here's a private bank, Congress is responsible. That's likely not what happened. This is a policy that the congress never even campaigned on. We find nothing. Essentially for district receive banks, the congress or the coalition UPA is not any more likely to win elections and nothing happens to vote shares as well.

Speaker 5:

Was there any evidence of impact on the economy?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yes. That's not our paper. That's the other paper by Young, I think Nathaniel Young. And he found some [inaudible 00:28:05].

Speaker 5:

[inaudible 00:28:05] of the same [inaudible 00:28:06].

Priya Mukherjee:

Exactly. This policy we came across at someplace but then he wrote a paper first as part of his dissertation [inaudible 00:28:16]. So there's no discontinuity, just pre demonetization as well on vote shares in the pre period. Like I was saying, why was the congress party not rewarded, maybe gained manifest over time, but it's really not salient. Maybe voters don't know how to attribute credit, but that's not something we can really identify in our paper. There's other work looking at the economic impacts of the monetization using different kinds of identification strategies. We wanted to make sure that we can replicate some of those results using our sample and our identification strategies.

Similar to some other work that [inaudible 00:28:57] and others have done, we do find that economic activity as proxy by nightlights was less or was worse in places with more severe demonetization as defined for us. We do a difference in discontinuity looking at monthly nightlight data before and after demonetization around the threshold for districts and this is the specification that we have. What we find is that places with more banks after demonetization have relatively more economic activity if you believe nightlights as a proxy for it as others have done. Now that brings me finally to the electoral effects and I think I'm like maybe have 10 minutes?

Speaker X:

Sure.

Priya Mukherjee:

Or five more?

Speaker X:

10. That's right.

Priya Mukherjee:

I'll try to rush through the main effects. We have this data on was demonetization the right move? Do they like the policy and so on. We did some descriptive work that I won't spend much time on. What are the correlates of support? This is a regression with support on the left hand side with all of these on the right hand side, it's conditional. We can run these separately as well, but it's fairly consistent that it was a little surprising to me. I actually thought that if you're a formal sector worker, maybe you would support it more relative to informal, but that's not really what we see. Some of these other religiosity and religion that seem to correlate with support for the policy.

Before going electoral effects we want to look at voter views and what we find is that voter... This is just a cross section. We can't do difference in this continuity here because we only had that one point in time it was measured what the voter views were in May, 2017. This one's a little bit noisy, but what this shows is that around the cutoff voters that were less badly, or they had more banks, so less severe monetization were more likely to say this was a good policy relative to people that were worse hit. It's the opposite if the person is saying that it was done with bad preparation.

Speaker 7:

What about if they just said it was bad?

Priya Mukherjee:

It was I think similar [inaudible 00:31:27] it was just a much smaller fraction, so it's a little bit noisier.

Speaker 5:

So the difference between two columns are the bandwidths?

Priya Mukherjee:

The difference these two? Yes, that's right. Yeah.

Speaker X:

These are [inaudible 00:31:39] optimal bank rates.

Priya Mukherjee:

So this one is not for the state RV. We are doing different types of optimal bandwidth including MSC. This one we just made a consistent with our electoral results. Remember the electoral results are different in this continuity for which I'm not aware of any method to choose optimal bandwidths. For those we do different, we use these and I'll show you robustness to different bandwidths for those results as well. This particular table is consistent with what we have there, where we could do upload with this one as well. Since this is a cross section. Finally, was the BJP punished for demonetization? The answer is yes, they got relatively fewer votes and effect sizes were significant.

This is a specification we have, which I won't repeat again, it's a difference in this continuity and this is not the difference in this continuity table. This is just looking at differences around the cutoff in changes as the outcome variable. Just visually what you will see is if you got more banks or if you have less banks and more severe demonetization, the BJP is essentially less likely to win. But maybe this one is little bit easier. Sure you have the optimal bandwidths, but this is not a preferred specification. This is just the simple difference with simple RV. If you receive more banks, you are more likely to vote for BJP or an ally. On the flip side, if you received less banks, more sever demonetization, you're going to punish BJP.

Speaker X:

Can you give a sense of the... Well, okay, do these actually close? Yeah, that's fine. No, you can go ahead. Go ahead.

Priya Mukherjee:

So sorry, go ahead. [inaudible 00:33:38].

Speaker X:

No, no, go ahead. It's fine.

Priya Mukherjee:

Okay. Yeah, so we have board shares, we have probabilities. The difference in this continuity... So this is our most conservative estimate essentially. Vote shares for BJP is higher with less severe modernization or we can say lower with more severe demonetization by almost five percentage points. Then it's even higher if you look at coalition, [inaudible 00:33:53] coalition, probability of winning is also pretty large effects as you see. We wanted to give a sense of what's happening before demonetization. We don't have a whole lot of elections afterwards and because you have very few elections for your very few states, we group them in bundles of years and it's relatively flat before, so we were happy to see that.

The last thing I'll say is that is our robust to different things, bandwidth selection. We do different falsification tests just set 2014 randomly as a demonetization year and just run the same analysis. We don't see anything there. We include constituencies based on how the outcome variable is defined. If a party doesn't feel the candidate, do you treat that as zero vote share or do you treat that as missing? We do it both ways. It's fine and then it's robust. Then we also... This is the most recent thing, it's not in the paper yet. We did it for our revisions. We do different types of fixed effects, and there's reasons to thank this could matter and our results are robust to this as well.

This is just showing for different bandwidths what's happening to the effects as we would expect for the smallest bandwidth it just gets a lot more noisy. The very last thing I'll say is nothing happened in strongholds. In stronghold... This is a difference in this continuity with a further difference where we're interacting with whether a constituency is a stronghold or not, coalition versus BJP. It's essentially wiping out any differences that we're coming from the severity of demonetization. We have some conjecture on why this might be the case. But the way we're defining stronghold, it's actually a fairly large traction of the country.

What this is saying is for big chunks of the country, even if you're negatively impacted, which we check for... So if you're in a stronghold with more severe demonetization less night lights, and what we've looked into now for our revisions is it's not the case they're getting more [inaudible 00:36:08] jobs, it's not the case that you're getting other transfers. You are negatively impacted but you're still not responding electorally to being economically hard.

Speaker 7:

[inaudible 00:36:19] stronghold?

Priya Mukherjee:

Which one? Yeah. In this particular... We can do it in different ways. For these estimates, I simply look at the number BGP wins or NDA wins pre demonetization and I just split into above and below median. Sorry.

Speaker 7:

[inaudible 00:36:35] is that the constituency level?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yes. I just split it into above and below median. It's a split. You could do it in different ways and it's actually not very different. And yeah-

Speaker X:

But all ACs in a district basically got assign the district score of [inaudible 00:36:51]?

Priya Mukherjee:

No. This is by ACs. On the left the data is at the AC level, the treatment is at the district by year level.

Speaker X:

Right. But so all ACs are basically assigned to that. I mean all the ACs in the district.

Priya Mukherjee:

No AC by AC actually.

Speaker X:

Oh, okay.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, so shat particular AC, it's a number of million that AC.

Speaker X:

Oh no, no, I'm saying in terms of the treatment, the banking thing was for all ACs in that district-

Priya Mukherjee:

Exactly. Sorry yeah.

Speaker X:

... are basically treated the same? Yeah okay.

Priya Mukherjee:

Exactly. Yeah. All the ACs have exact same treatment and that's an assumption that we made.

Speaker X:

And you cluster by the district?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yes, yeah. Like I was saying, night lights, it's not the case that the interactions are any different. They're also impacted, the stronghold are also impacted and so on. I just end, by sort of summarizing and a few conjectures on why we don't see stronghold, maybe that's open for future research. But to summarize, what we did was we used a regression discontinuity design and further more a difference. In addition to that to look at the electoral effects of this fairly popular policy based on all of the data we saw. In fact the fractions were much larger than my priors, and it had significant economic costs, at least in the short run, even if they've gone away over time.

The ruling party had growing support on average, but relatively speaking they had significantly less support as we so showed in districts with less access to cash and banks. It's a little ironic because the party rewarded, BJP was rewarded more in districts with more banks and they had more banks because of the oppositions policy a decade prior. So this one had, we see the total effects, this one not. I don't think we're under powered on this likely because [inaudible 00:38:36] matters, but we can't definitely say anything on that. Then finally the impacts were driven by non-stronghold areas, or areas that have not much history of BJP support. And again conjecturing that policy spaces are multidimensional and citizens get one quote.

That's likely, if you're more aligned, you're not going to be as responsive to one particular policy like this. Then finally, like I mentioned, we looked at some other standard things one could look at and these results are not being driven by turnout or incumbent or anything like this. This question was asked in national elections we find similar but very noisy effects on national elections. That's not too surprising given all of the issues and the assigning treatment to parliamentary [inaudible 00:39:28]. Okay. Thank you. [inaudible 00:39:31].

Sarath Pillai:

Well, we have a good 20 minutes at least, so please have a go if you want to ask questions.

Speaker 7:

This might be more of an interpretation question, but as understood it, the districts that got a lot of banks were also growing faster. If you're growing faster than your economic circumstances are improving marginally over time, so they might be less sensitive to a negative shock than you would be if you had been growing facts. So in a way it seems like that would be very correlated then with the policy that you have, which makes it a little hard to know whether it's access to change out your cash or it's that you're just hurt less by the policy in the sense that you don't notice it's impact left on you because you feel richer.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, so we had... I didn't talk as much about it. Before, after difference and some controls district fixed effects would get at some of this but not-

Speaker 4:

Not growth though. It would [inaudible 00:40:37].

Priya Mukherjee:

But not, yeah, not growth yeah.

Speaker 4:

[inaudible 00:40:38] I don't think it matters fundamentally to the end result. I think what it does alter the interpretation [inaudible 00:40:43].

Priya Mukherjee:

It does, yeah, yeah, yeah. Depending on how much [inaudible 00:40:47].

Speaker 4:

[inaudible 00:40:47] also helps you rule out maybe a little bit. But one way you could test that is to see whether stronghold are economically better off or not. Because it's not then it would argue against what I just shared as a channel.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah. We can look more into what's happening to growth versus different kinds of districts yeah. Yeah?

Speaker X:

Thank you so much for this. Could you help us really understand the political impact of what the result is? So in the paper you say that were 10% decrease in bank branches is associated with a 0.9 percentage point increase in BJP's vote share. What was the typical discontinuity bank branches in the country and what was the BJP's winning margin? Because of 1% decrease in the BJP's vote share in 2014 and '19 does not... I don't think it would've moved the needle all that much.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, I think that's a really great question. I always find it challenging to think about what difference it makes when you're forming a government, especially in a place like India where there are much coalitions happening. I don't have a great... very good answer for it. I mean you can get a sense of what's happening to probability of a candidate winning here, but how this translate to, and I would love to hear your ideas on this for not just this project role, my other projects as well. How do you translate probability of winning to what's happening in state governments, and also at the state level if you were to look at something more aggregated we're currently, totally underpowered.

Speaker X:

May I give a solution?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah sure

Speaker X:

It seems stronghold measure is basically capturing western India. Because if you look at prolonged incumbency in the BJP since let's say 1999, then the states are probably areas where it has a straight contest for the populist. Maybe one story that's going on here is where you don't have a credible opposition, the voters don't punish even a bad policy. Wherever there is some semblance of contest there seems to be a punishment. Maybe the splitting variable is not so much party stronghold but effective or credible opposition and you may see that there's heterogeneity on that [inaudible 00:43:04].

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, I think... Yeah, that's a really interesting point because it comes to how we're interpreting this heterogeneity itself. What is it about the stronghold? So we did something similar on for the state as a BJP rule state, we find similar effects. Maybe if you're right then if you look at is there a strong opposition, and we put it up that maybe we'll get something similar. What we have not done in this paper and we aren't able to do properly, maybe we could do it in future, is unpack the stronghold really carefully, which we haven't done. Yeah.

Speaker 7:

So I guess on that this, I was thinking about I, one of the way... My intuition on how to interpret the stronghold is in some sense these are places where you perhaps have fewer sort of elastics voters who are willing to switch back and forth, especially when think about like [inaudible 00:43:55] for the BJP so we think about a pretty short period in which a lot of people are shifted toward national level, but broadly the [inaudible 00:44:04] states as well right? A lot of people are shifting to the BJP prior to the monetization. So if we think in it's precisely in not stronghold and weakholds if you will, that you see more of this recent shift. It seems plausible that those are the people that are much more willing to then shift back in response to this as opposed to places where there's stronghold, where [inaudible 00:44:25] pretty deep [inaudible 00:44:28].

I would interpret it as the sharing the electorate is relatively elastic and so a bit more responsive, these types of things. And then it's somewhat related, maybe not. In terms of the framing I guess as I read the first couple pages of this idea of a framing of popular [inaudible 00:44:49] popular policy, I guess thinking about a lot of the work on public opinion that shows how much partisan identity shapes attitudes on issues which we do in relatively complex ones. I guess I would approach the responses on something like this cross-sectional survey with a healthy dose of skepticism that that's getting it a real genuine preference and it's not just reflecting underlying support for Modi. Especially given when you talk about right, it wasn't actually sort of economic benefit, right sort the formal sector.

It was stuff that seems like it's pretty strongly correlated with Modi support. So just in terms of thinking about how you frame the paper, I actually thought it equally a different but equally interesting framing would be sort of like what is the impact of bad policies from popular politicians? So it's not the populism per se, it's still getting [inaudible 00:45:43] how latitude do popular politicians have to essentially do things that harm voters? I think your answer is basically in places where that policy is really where that leader is extremely popular, there are pretty minimal effects. In places where maybe some of that sort of support is a bit shallower in the sense that more people that have recently switched there are impacts some electoral [inaudible 00:46:08].

Priya Mukherjee:

That's really helpful yeah.

Speaker 7:

I think that to me that's on a little more solid footing and you're not sort of worried that... Someone could come along and say I don't think this is a real, [inaudible 00:46:19] but that's fine. We're not hanging our hats on that in the way that... I worry a little that sort of the current framing, you really sort have to buy the idea that people really like this policy, [inaudible 00:46:29] all you need is accept that they buy that Modi said it was a good policy.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, that actually really helpful because we're currently in the process of revising the introduction so it's like that's really helpful. Yeah. Thank you.

Speaker X:

Speaking [inaudible 00:46:44].

Speaker X:

Oh sorry Rajit. Rajit was raising up your hand and [inaudible 00:46:47].

Speaker X:

Sorry. I had one thought, I don't know if it actually [inaudible 00:46:52] but a lot of the conversation around demonetization was also how it teamed out [inaudible 00:47:16] because the BJP had [inaudible 00:47:16]. Just in relation to [inaudible 00:47:16] point about stronghold and where [inaudible 00:47:16] is was able to perform better or was [inaudible 00:47:16]. I don't know if there's any measurements of like how much the [inaudible 00:47:16] was able to spend. But something like that, I don't mind being [inaudible 00:47:24] unpack the stronghold [inaudible 00:47:24].

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, I mean that's just a general point that's always hovering in the back. because that was a claim that was made, right? Oh that was one of the reasons why this happened, et cetera. I mean if that is happening like a boring response is that oh that would go against our results, so likely the results are even greater because that... I don't know, I don't have good ideas on how to get it. I mean one, there's probably suggestive things one can look at like are for example, congress candidates less likely to run for a reelection cause now they have less access to cash? Those are things one could look at.

Speaker X:

I also have a follow up question. Do BJP generally change on like election [inaudible 00:48:01] and demonetization [inaudible 00:48:03]. But historically our all people vote at the state level, but just how people vote at a national level, it's different. So you're managing the state [inaudible 00:48:16], I'm curious about, it's not obvious that people would necessarily punish state level politicians for a national level policy and I'm just wondering how you're thinking about that. Now it's different, so now everything is about Modi but [inaudible 00:48:31] like slowly getting there? I don't know. I was just wondering about how you [inaudible 00:48:36] that?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, I mean ideally we would've looked at, had access to more national elections that happened maybe soon after demonetization that could be matched well to districts. I mean this is looking at state elections, not an answer to your question, but looking at state elections is more common in the literature just because of the data constraints. That's really the reason. It's not because it's conceptually better to look at in any way. I mean we could possibly do more to look at voting behavior state versus national. I mean I know that CSDS has other surveys. They do the pre poll and post poll surveys before every national state election, and they do ask questions on state versus national, their views on elections and who they voted for. That's something I could look at.

Speaker X:

And views on Modi.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, and use on... Do they ask in all the elections?

Speaker X:

They were in [inaudible 00:49:35].

Priya Mukherjee:

Okay, I see.

Speaker X:

[inaudible 00:49:35] before that yeah.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, because the mode of the nation is a different one. It wasn't a pre-post poll, it was just a special thing in May, 2017. I don't have a very satisfactory answer for [inaudible 00:49:46]. I do think people are relatively aligned, but that's not a general thing fact at all. If you know the politics of different states. Yeah.

Speaker 4:

There were also some type-

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah. Go ahead, yeah.

Speaker 4:

[inaudible 00:49:59] some state that have examined [inaudible 00:50:00].

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, I mean I guess yeah. I mean to look maybe pulled whatever because constituencies are fully nicely in parliamentary constituencies. One could look at how correlated these things are. They are fairly... At least that's why, that's one of the reasons we looked at coalition as well. I think that's actually important. But yeah, we could probably do more. But I don't think there's a huge misalignment between these two things. The national election results that we have are kind of consistent. I mean depending on how you assign districts to parliamentary constituencies, it gets worse or better politician.

Speaker 4:

[inaudible 00:50:44].

Priya Mukherjee:

Tanya had a question?

Tanya:

Yeah hi. You mention that you [inaudible 00:50:51]?

Priya Mukherjee:

Which one?

Tanya:

[inaudible 00:50:55] effects.

Priya Mukherjee:

No, we have [inaudible 00:50:56] and all, as robustness check, we additionally had district fixed effects and state by your fixed effects.

Tanya:

So did you see a difference in that in yours because you have [inaudible 00:51:08]?

Priya Mukherjee:

I see, I see. Your question is what were the effects over time? We now have done that in our [inaudible 00:51:24] responses. It's very hard because not so many elections afterwards. So what we did is we grouped... So after demonetization we have approximately 18 months. We grouped six months of election, six months of elections, six months of elections. These three. We looked and in non-strong whole, the way we defined it, it affects state. In stronghold there's a slight electoral effect versus basically totally zero, second and third period. That's actually really interesting. I mean if we can extend this, that would be really interesting to look at how quickly things go away because the economic effects indeed were... other things started becoming more up of mind.

Tanya:

Yeah because also from just memories from which is an evolving narrative why demonetization happened. There wasn't a [inaudible 00:52:28].

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah.

Tanya:

Even when [inaudible 00:52:28].

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah. It's not the case that the stronghold... For sure what we see, at least in what we've been able to do, it is not the case that stronghold started responding later, they did not in the way we defined strongholds yeah.

Speaker X:

[inaudible 00:52:41].

Speaker X:

So following up that question of the evolution of the narrative and the dynamics of the time I'm wondering if [inaudible 00:52:50] anecdotally or more systematically if there was any kind of compensation that actually strongholds were getting for the effects?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, that's a really good question. We have tried to look at that now. One thing we can do is we have managed to extend the nightlights data just to see if broadly economically there's any differences in strong areas. At least in the months we looked at there wasn't. We looked at Naraga jobs, people walk, things like that. There was nothing on that. We couldn't think of too... Maybe we looked at, I think banking loans received that data. We didn't see anything different in stronghold areas. If you have other ideas and other things we can look at, we certainly could... But Naraga is the biggest one, and also first credit access.

Tariq Thachil:

Thanks a lot. That is really interesting. Just a couple of quick one, I just wanted to underscore that I don't think my understanding of populism, this is not populist because nobody knew about it. There's no basis for thinking it was popular. It could be then made popular through the reader. Just to support that, I think you have a lot here and you don't need that. That will become a red herring. Second, I want to just come to this coalition's finding.

Because if I'm reading it correctly, it's that, so the BJP alone versus the coalition, I'm just trying to think of what's happening with the coalition partners and the allies and why is that affect seeming it's stronger than a BJP alone effect? And how that then affects our interpretation of not a strong hold, but what's driving this. Why would it be if that's the logic that, if I'm interpreting that correctly. We haven't really talked about the coalition finding vis-à-vis the BJP finding. How do you guys think about that?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, so it's possible that this is something to do with the point raised of state versus national. I don't really know how to impact, I mean I can make some guesses on why [inaudible 00:54:44].

Tariq Thachil:

But if it is a stronger effect when it's BJP versus ally?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah it is.

Tariq Thachil:

That is correct right?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, that's correct.

Tariq Thachil:

I think at least again, to the degree that this is how you... I think it only matters because of how you're interpreting it. It's not [inaudible 00:54:52]. But I think it does matter because if you're invoking this idea of stronghold and these very fixed partisan, then that doesn't make me think that the allies would be the ones who are driving the results. If the model in the mind are these fixed partisans who certainly become fixed onto this charismatic leader, then that doesn't really square with the ally versus BJP result to me. So I think it does need to be unpacked at that level for interpretation. I'm trying to think, off the topic, I can't think how we'll to do it, but yeah, does that make sense? Is it [inaudible 00:55:22] make sense? Yeah.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah [inaudible 00:55:23] I mean I'd love to hear thoughts on what might... So on the ground, how the demonetization was being explained by a BJP person versus an Allie. Then I think this is also somewhat, the difference is also a little bit sensitive too whether you could have a party not feeling a candidate as a zero or not, which can also make a bit of a difference. But you're right. There's probably stuff to unpack here that we have not at all done in the [inaudible 00:55:52]. This is similar somehow, but yeah, the vote share is for sure.

Speaker X:

So when you do only BJP there were more observations than when you do BJP or Allie?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, because we have some and coding of all of the parties, which for some we were not sure. But if we make the sample the same, it's fairly... I mean it's not very different. Yeah.

Speaker X:

[inaudible 00:56:16].

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah.

Speaker X:

No, that's really good.

Speaker X:

I just have a clarification. Sorry I can't read most of your analysis, but you said that severely impacted regions which are also unbanked regions reacted poorly, right? But if there were strongholds, they continue to react as... they forgive the populist policy. Do you know the intersection between bankable regions versus BJP strongholds? Because I would imagine urban centers, middle class formalized sector, which also support like BJP by the way could also be banked right? So do you know like regional?

Priya Mukherjee:

I see, I don't remember what the correlation was. So the stronghold things that we're looking we're basically seeing among stronghold, if you just focus on stronghold, stronghold districts around the cutoff before and after, that's the comparison we're making. It's within that group. But it's possible that there are some correlations between being a stronghold and other characteristics.

Speaker X:

Right.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah.

Speaker 7:

Just a comment to help you start to price this.

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah.

Speaker 7:

One thing that this suggests, given the difference is much larger in the bottom, is that the vote share change is really happening in places where it is a strong win which is an interesting finding, right? Because otherwise you'd be flipping a lot more to probabilities of winning people who are under margin. So what that's telling you I think is that these effects are biggest, the [inaudible 00:57:56] Allie is biggest in these places where they're already doing [inaudible 00:58:02]. So maybe it has to do with it's interpreted, the policy is interpreted as being an ally [inaudible 00:58:08] the party, which is just crazy in those places where you've already [inaudible 00:58:12]. I don't know enough about politics [inaudible 00:58:14].

Priya Mukherjee:

Okay, yeah, yeah.

Speaker 7:

But I think this gives you some [inaudible 00:58:19] to think about where it's happening, which might tell you [inaudible 00:58:20].

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, Yeah, no, definitely. I think that's really interesting question that's been brought up, that I need to think a lot more, the effects [inaudible 00:58:31] whether that's a possibility.

Speaker 9:

Could I ask just a question that basically comes out of very lay familiarity with this demonetization policy, which is where does the fact of social economic diversity of the orders appear in this project? In the sense of, doesn't matter whether someone is a middle class or a poor or a rich, or does it matter whether someone has a history of party affiliation or what you might call us ideological factors? Or do these factors-

Priya Mukherjee:

I see. Matter in the electoral response?

Speaker X:

Yes.

Priya Mukherjee:

I don't know. We haven't looked at that. We could would have to cut the data more essentially to try and get... So we don't have voter level data, but you could get some measure of what fraction is socioeconomically worse off and look at the heterogeneity that way. Yeah.

Tariq Thachil:

You could potentially look at CSDS constituents. I mean that's again, shrinking example but that's an easy way that doesn't require survey technology to look at and see [inaudible 00:59:37].

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, I mean, yeah, that's true. I mean just looking at the correlates of support, I was like, okay, this is not correlating with things that you would expect on social... I mean, yes, on ideological grounds, but not so much on... We looked at other things, occupation and other things and just because of that we didn't go so much into the heterogeneity of electoral effects just because the correlates were just so unexpected and not along the lines one would think, but that is something that we could do. That's something that we don't have enough. Questions?

Tariq Thachil:

Just one, then just I'll ask it since we're time and I just, I'm genuinely curious, you guys refer to it. The thing is that two years ago I saw a presentation on a paper, which you guys mentioned that has a completely the opposite finding and also looks at a banking reform earlier.

Priya Mukherjee:

That's my colleague [inaudible 01:00:36].

Tariq Thachil:

I know your colleague [inaudible 01:00:36]. I'm not asking you to say who is better or anything. But as a genuine interested observer I want to know how do we... I mean if we're interested in what was the effect of [inaudible 01:00:49] banking reforms or, it's kind of the elephant in the room for me which is, I want know kind how-

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah. What happened? Yeah.

Tariq Thachil:

...to think about this. Is it about... Obviously they have a slightly different methodological approach, like a different banking reform. I'm sure you guys have talked about this, but can you give us some like... what do we do with this when we leave the room? How we spread that circle?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, for sure. I mean I'm obviously completely biased [inaudible 01:01:13].

Speaker X:

We know, as you should be. But-

Priya Mukherjee:

Put it out there, but [inaudible 01:01:16].

Speaker X:

But just intellectually, what do you think is going on there with that?

Priya Mukherjee:

Yeah, okay, so the first is the sample. The huge difference in sample variation that shouldn't make a difference to the answer to the research question of course, but it does because here we have... I mean it's, sure it's RBD difference and discontinuity. It not all of the districts in India, but in that case I think it's 75 districts. It's just one part of the country, far fewer districts. But importantly, the policy that they're using is from the '70s and '80s.

This policy, we believe just flipped that variation, right? The place, the districts... and this is used in [inaudible 01:01:55] paper. The districts that had fewer banks as a result of the old policy were exactly the one that had a lot more here. It's literally the opposite. It's not a surprise to me even with 75 districts because they would have the opposite results. Yeah.

Tariq Thachil:

Okay. So...

Priya Mukherjee:

I think that's what's going on. But yeah, I don't... That's...

Tariq Thachil:

Okay, thanks for indulging question.

Priya Mukherjee:

So I do believe my results.

Tariq Thachil:

That's okay. Thanks for indulging the question. I was just curious because I was reading it as like, okay, I just want to... I have to ask. Then I was like if we're over time I think I can ask. Yeah. All right. Thank you very much.

Priya Mukherjee:

Okay, thank you.