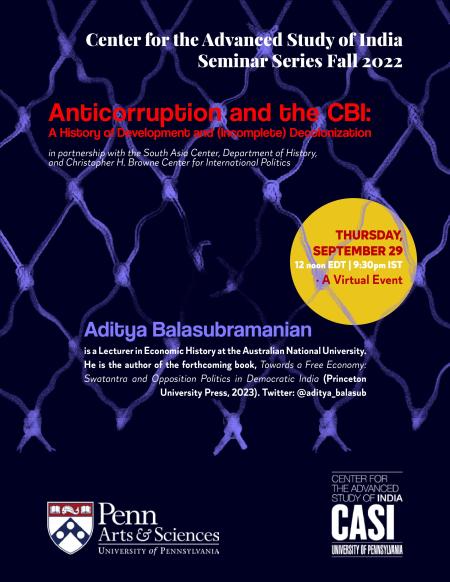

Anticorruption and the CBI: A History of Development and (Incomplete) Decolonization

(English captions & Hindi subtitles available)

About the Seminar:

Despite its dubious constitutionality highlighted by the judiciary and calls for major reform that date to the 1960s, India’s Central Bureau of Investigation continues to operate as an appendage of the executive branch that loyally does the bidding of the government of the day. How did things get this way? This seminar examines the surprising transformation of a minor Special Police Staff created to deal with officials pilfering supplies and awarding fake contracts during World War II into the Central Bureau of Investigation, a body enjoying criminal investigative powers over the whole citizenry and across a vast range of offenses. The broadening of this institution’s ambit can only be explained in the context of the interplay of two competing logics articulated as such by the postcolonial theorist Sudipta Kaviraj. The first was the logic of bureaucracy, which saw the retention of colonial era laws and expansion of existing institutions to deal with the “emergencies” of decolonization, statist economic development among the most powerful. The second was the logic of democracy, and the increasingly vocal demands of accountability and discourses about corruption voiced by an enfranchised citizenry. As these logics competed, governmental rationality grew increasingly complex, sometimes more performative than substantive. Over time, the anticorruption apparatus itself became corrupted. Building on recent scholarship on decolonization, economic development, and corruption in South Asia, and making use of a vast range of sources, this seminar illuminates one of the paradoxes of the Indian present.

About the Speaker: Aditya Balasubramanian is a Lecturer in Economic History at the Australian National University and the author of the forthcoming book, Towards a Free Economy: Swatantra and Opposition Politics in Democratic India (Princeton University Press, 2023). The book challenges accounts of the rise of neoliberalism as an anti-democratic, expert-driven phenomenon projected from the North Atlantic onto the rest of the world. Instead, it presents a case of how actors responding to the concerns of the local political economy in the decolonizing world drew on the idioms and practices of anticolonial nationalism and neoliberalism to articulate an Indian economic conservatism. Aditya has also published several articles on the social, economic, and intellectual history of mid-20th century India. He is currently starting a project on the modern history of roads and road transport in South Asia and a long-term history of family businesses operating between South and Southeast Asia.

Aditya Balasubramanian is a Lecturer in Economic History at the Australian National University and the author of the forthcoming book, Towards a Free Economy: Swatantra and Opposition Politics in Democratic India (Princeton University Press, 2023). The book challenges accounts of the rise of neoliberalism as an anti-democratic, expert-driven phenomenon projected from the North Atlantic onto the rest of the world. Instead, it presents a case of how actors responding to the concerns of the local political economy in the decolonizing world drew on the idioms and practices of anticolonial nationalism and neoliberalism to articulate an Indian economic conservatism. Aditya has also published several articles on the social, economic, and intellectual history of mid-20th century India. He is currently starting a project on the modern history of roads and road transport in South Asia and a long-term history of family businesses operating between South and Southeast Asia.

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Sarath Pillai:

Hello and welcome, everyone, to CASI’s seminar series. My name is Sarath Pillai. I'm a postdoctoral fellow at CASI and one of the organizers of the seminar series along with Amrita Kurian and Tariq Thachil.

I want to make two quick announcements before I go to the speaker for today. The first is a CASI celebrating its 30th anniversary in two weeks time. In order to celebrate the anniversary, we have organized a day long symposium on October 13th. The symposium will take place on campus in person, so if you're in Philadelphia or in the nearby areas, please come and attend it. This is a public event. Anyone can attend it and all the details about the symposium and the exciting lineup of speakers is on our website. The second is the usual Thursday seminar will resume on October 20th. So the next Thursday seminar will be on October 20th where we will have Smitha Radhakrishnan from Wellesley College speaking to us about gender and finance. That will be a fully online event as well.

So today we are extremely delighted to be able to host Aditya Balasubramanian. He's a lecturer in economic history at Australia National University. He's currently a fellow at the Center for History and Economics at Harvard University. Aditya is not new to Harvard. He received his undergraduate degree there and then he went on to do his MPhil and PhD in Cambridge University as a Marshall Scholar. He is the author of the forthcoming book Towards a Free Economy: Swatantra and Opposition Politics in Democratic India. This is forthcoming with Princeton University Press in just a few months. The book already has a website. If you are interested, please check it out. He's the author of many articles and especially noteworthy is this article on Economic Conservatism and Democracy and License Raj that came out with Past and Present in 2021.

Today he's going to be speaking to us about the CBI and corruption in India and the title of his talk is Anti-Corruption and the CBI: A History of Development and (Incomplete) Decolonization. So most of you're familiar with the format. Aditya will speak for about 30 to 35 minutes after which there will be Q&A. If you want to ask questions, please type in a personal message to me, Sarath Pillai, and I will call on you to ask your question. You can come online and ask the question. And the talk is being recorded, so please stay muted with no interruptions unless you're speaking or asking a question. Thank you. Over to you out Aditya.

Aditya Subramanian:

Well thank you so much for having me. It's really a delight to be able to be here and weekly present in this sort of 30th anniversary seminar, sorry, seminar series. Let me, there we go. See how this works. One second.

Yeah, so I guess I was saying before we started that the work of people attached to CASI over the last 30 years has been very important to me. Chief among them, your founding director, Francine Frankel and it's been in many ways so foundational for my work and the work of others. So absolutely sort of thrilled. So with that, I'll kind of get started because we don't have too much time.

So in 2013, the Guwahati High Court in the Indian state of Assam declared the existence of the country's apex investigating body, the CBI to be unconstitutional. 50 years previously in 1963, this agency had been brought into being by resolution of the home ministry as the Central Bureau of Investigation and as a police force dedicated to anti-corruption. Its powers quickly widened beyond anti-corruption to cover crimes like murders, kidnapping, and terrorism. Crucially, for categories of crime that did not merely implicate public servants included within the body's purview, the state was given license to investigate private citizens from 1965 onwards. The 2013 court judgment asserted that because the resolution creating the CBI had been passed only by the home ministry and not the cabinet and done so without the ascent of the president, its creation had been illegal. And even though there was a constitutional provision for a Central Bureau of Intelligence and Investigation at the constituent assembly, the definition of investigation discussed was general inquiry that was distinct from criminal investigation, which only police have the power to conduct and police under the seventh schedule of the Indian Constitution is a state rather than the union subject, meaning that states raise such forces and their consent is required to have in the investigation within their borders.

Although the CBI is commonly understood to derive its powers from the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act of 1946, the resolution creating the CBI never referred to this as antecedents. More problematically the only police force that the Delhi SPE could raise under the 1946 act would be for a union territory, not for the central government. After the judgment, the case was sent for a hearing by the Supreme Court of India. For about a decade, the court has stayed the case and it remains to be heard. Meanwhile, the fate of over 9,000 investigations and 1000 trials hangs in the balance. Especially since the 1970s governments in power have used the CBI to go after their enemies. P. Chidambaram, who arrested Amit Shah, and Amit Shah who had P. Chidambaram arrested are the two latest in this game. The retired Supreme Court Justice R.M. Lodha in 2013 called the CBI quote, "A caged parrot speaking in its master's voice." Unquote. Since 2018, 9 non BJP states have declined to give their consent to CBI to probe for crimes allegedly committed in their territory. More recently [inaudible 00:06:37] the executive the Supreme Court has expressed concern over these withdrawals of consent.

In this talk I want to address two questions. One, how does one account for the persistence of corruption discourse, the evolution of anti-corruption institutions and the bizarre phenomenon that the investigative body for anti-corruption against state officials has been turned against the people of India today? Taking a step back, I want to ask, how does governmental rationality or governmentality evolve in a postcolonial society where you have the dual inheritance of colonial institutions and anticolonial nationalist leaders as masters of those institutions as often with emancipatory aims or politics? In India, this is further complicated by the fact that the state begins to reckon with democratic demands under the conditions of universal enfranchisement and accountability to their citizenry and assumes increasing and increasingly vague responsibility for the phenomenon of development.

Through this history of development as embodied in an institution like the CBI and its antecedents, I seek to link the new history of decolonization in South Asia and I'm thinking of the work of Kalyani Ramnath, Rotem Geva, Radha kumar, Ornid Shani, Rohit Dey, and the history of development, I'm thinking of Nikhil Menon, Ben Siegel, David Angerman, Matthew Subsher to the social scientific work on corruption and accountability done by scholars like Pranb Vardhan, Akhil Gupta, Nainika Mathur, William Gould.

My focus is the relatively under explored topic of anti-corruption. What do I mean by embodied? I mean one that at an embodied history it concerns an institution. The focus here is so that we get to everyday practices and consequences of development rather than merely the discourse of development or overarching development strategy that has tended to be the focus of these literatures. To address these questions, we have to go back to the transformation of the relationship between state and economy in World War II. The three parts of this paper move chronologically and hinge on major points, periods of change in anti-corruption. The first is world War II. The second spans postwar demobilization to the early 1950s, inauguration of five year planning. The third is during the 1960s during the sort of crisis of planning. Each of these is a stage in the evolution of a more complex governmentality.

The Special Police Establishment and the issue of anti-corruption in the central government service is a thread that runs throughout. I examine how discourses of corruption evolve with examples from popular discourse at every stage to suggest that these institutional dynamics are connected to society at large. Guided by Akhil Gupta's point, the discourses of corruption are constitutive of the understanding of the state.

So stage one, World War II brought an economic transformation of the subcontinent. It launched a period of lopsided partial industrialization led to the exhaustion of the railways, major deforestation and the recruitment of over 2 million troops, something that is demonstrated in many time CASI [inaudible 00:10:06] Srinath Raghavan's book, India's War. India became the arsenal for the British War in Asia, contributing supplies and manpower across central, south and southeast Asia. For the first time, especially after the Japanese took Burma, the Government of India actively assumed control and management over the food supply and instituted control prices. However, this came in the aftermath of, or at least well into, while the Bengal famine was unfolding. It was a case of too little, too late. Fortunately...

Just a second, the air in this room is a bit loud, so I apologize in advance for that, but I'll try to speak over it and hopefully it's not too distracting.

So the movement of manpower and supplies during the war also required the quick construction and repair of roads and rail lines, barracks and storehouses. To manage these processes the Government of India created various new departments, recruited new personnel and passed emergency wartime laws under the Defense of India rules. In the interest of time, I'll leave out the sort of quantitative details and I won't bore you with the charts, but structurally this created new instances of what economists like to call the principal agent problem. A conflict between one entity like the state and the representative authorized to act on its behalf. Social scientists have expanded this framework to consider the person on the receiving end of the activity as well. And so for my purposes, I want to use a slightly reworked framework of the social scientist Diego Gambetta, a tripartite relationship between trusters, fiduciaries and recipients in which the trusters are the Government of India. The fiduciaries, the bureaucrats, and the Indian people are the recipients as you see on the slide.

The government endorses the bureaucrat to distribute a resource, issue a contract, or manage some process with broader purpose. The Indian person can be anybody from a recipient of food at a controlled price to a contractor building a makeshift shelter. Economic theories have shown that [inaudible 00:12:23], conditions of scarcity and equality and inequality can increase incentive for the abuse of office by raising the rent seeking potential of the bureaucrat. I'm thinking especially of the essay by Abhijit Banerjee in 1997 called the Theory of Misgovernance. This was certainly the case in India and more so in the war. Over the course of the war, the number of these truster fiduciary recipient relationships multiplied. Given the UK's kind of battered financial position and Japan's steady progress into maritime and mainland Southeast Asia scrutiny turned to the supply base of British India. Apart from the bribery of officials, the issue of fake contracts and weaseling away of resources for sale on the black market became a serious concern.

So to combat this bribery and foul play associated with the vast increase in government activity during war and to bring government officials to trial, the Government of India created a Special Police Staff in 1941. Under powers of emergency war time legislation, it was placed under the exclusive authority of the governor general and empowered to act swiftly. As the war proceeded, the staff was legally reconstituted, expanded, and given greater powers. In 1943, an ordinance formerly constituted this body as a Special Police Establishment of the war department. That legislation created a special tribunal for prosecuting crime related to store, supplies or work connected with the war and widened the body's powers to include investigating railways related corruption. Most of the cases the SPE investigated focused on activity that curb the strength of military operations or indirectly increased wartime expenditures. By far the most common offense was contractors supplying inferior quality materials to the military and paying off military officers to look the other way.

Mainly isolated incidents, the odd case might unearth large rings of corrupt contractors to be blacklisted from army supply jobs in the future. Contractors also paid bureaucrats to fudge accounts and show deliveries at a higher price then was actually paid and then split the difference. For their part wayward officials might sell military goods to civilians via the black market. Once these got into the hands of traders, they could be hoarded and allow prices to further rise. The federal provisions of the 1935 Government of India Act created challenges for the SPE because the act devolved powers like those over the police forces to the provinces. This created complications for recruitment to an all India organization like the SPE. Provincial forces themselves constrained by an inadequate number of qualified officials had little incentive to part with their staff. In fact, the SPE managed to secure less than half of the officers requested on secondment from the provincial police forces. However, once trial proceedings did commence conviction outcomes were satisfactory. The documentary record points to a concentration of cases in Northwest India where crucial transport routes lay for supplies to efforts in the Middle East, there was constant insecurity due to tribal unrest. Mostly, officers were charged under the Indian Penal Code of 1860 or the Wartime Defense of India rules. Conviction typically led to imprisonment or fines.

So far as the Indian public was concerned, the corruption of these officials was not a serious concern. Rather, the major popular issue was hoarding which was one of the contributors to the Bengal famine. Indeed, this was one of the major themes of the 1946 realist film, Dharti Ke Lal, Student of the Earth, of which you see a flyer in the slide and it was brought out by Indian people's theaters association. It captures how the protagonist farmer family sells their grain to a hoarder to finance a family wedding. Once scarcity hits, the farmer has to repurchase the grain at a much higher price and soon faces destitution. To seek better fortunes the protagonist moves to the city of Calcutta. There he finds that hoarded grain enters the homes of the rich while destitute migrants from villages starve on the streets. However, the colonial state was not necessarily interested in that problem. Another sort of piece of trivia is that Dharti Ke Lal is Zohra Sehgal's first movie. So for the film buffs out there.

To take a step back, what can we say about this period? Well, right as part of India's development history, this is a period of a significant shift where the state assumed new powers in economic life. In various domains, the Government of India demarcated the legal and created its other, the illegal, whether that was the illegal black market price, the illicit possession of foreign exchange, the fudge contract or whatever. The expansion of the state and its activities created new truster fiduciary recipient relationships and choke points for activity understood to be corrupt. Anti-corruption wasn't a concern so far as a concern connected to the war efforts. Indian's welfare was not important and it mattered only it overlapped with those more objectives. Institutionally, the state created an influential apparatus that sought to eliminate bribery and corruption. This is in a sense the most elementary form of governmentality and I'm using it in the same way as in Foucault's treatment articulated in security, terror and population and in the birth of bio politics.

So the state identifies a problem and then it seeks to eliminate it. That's the most sort of crude form. The greater complexity as we shall see arises later. And it's the war that sets the template for what happens in part two. So now we get to transitions. So on 15th of August 1947, as I'm sure all of you are aware, India became formally independent from Britain. Nevertheless, in the interest of managing political dissent and various [inaudible 00:18:40] pressures, the interim Government of India and dominion government, so '46 to '47 and '47 to '50 refrained from loosening the grips of wartime power as it contended with the partition, the integration of princely states, various separate [inaudible 00:18:54] and other challenges.

So well into the 1950s, two crucial features of wartime political economy persisted. First, the size of the state's personnel continued to expand the government economic activity. New departments of the government and positions of employment sprung up creating additional layers of the bureaucracy. Second, to manage scarcities, the Government of India retains specific laws controlling economic resources. So new fiduciaries with more powers were inserted between trusters and recipients who are transitioning crucially from subjects and decision. Government assumed responsibility not merely for controlling the pattern of production, but also bringing the poor along and ensuring a modicum of equality and distribution or modicum of equity and distribution. And because Nehru was hemmed in by a largely conservative balance of power in the Congress party organization, which blocked progressive developmental legislation, the sort of long and sad story of land reform, he relied increasingly on the bureaucracy to perform developmental roles often by executive fiat. And this is what Professor Kaviraj has called the logic of bureaucracy, which takes its antecedents in the colonial period. Pursuing economic plannings towards these objectives required recasting policies like rationing and price control of commodities as part of redistributive justice.

Quotas on exports and imports, capital issues, regulation of foreign exchange and high levels of taxation channelized resources for the first five year plan to stabilize the Indian economy after war and the partition of British India into India and Pakistan. As Rohit Dey has shown, post colonial economic laws cast India's under development as a permanent economic emergency. So you have the retention of emergency powers as you move from wartime emergency to dominion emergency and development as emergency. The Government of India continues to control prices of essential commodities and as part of this welfare imperative, it regulates the production, distribution, sale and storage of these commodities. However, the emphasis is on the provision of goods by the state rather than citizens rights to these goods. And so mirroring colonial privileges of the administrator, the post-colonial economic bureaucrat was given the arbitrary power to grant and revoke licenses and to impose and exempt licenses from certain conditions. The state invents the category of the socioeconomic offense and bureaucrats go after traders mercilessly as possible criminals.

Courts generally delivered guilty verdicts when these matters went to trial. So what kind of bureaucratic practices that you see connoting some kind of abuse of office? Well, you continue to see bureaucrats evolve in activities commenced during World War II. Hoarding, dealings on the black market, tax evasion, food adulteration, illegal trading and licenses and permits. These take on new life in the post colony. Railways are a site of corrupt activity that are particularly prominent, especially when there is more civilian travel that resumes in this period. The upgrade of infrastructure after wartime devastation, movement of traffic and freight schedules, contracts for siding in new tracks.

And so in popular discourse and in government inquiry reports, we hear accounts of railway bureaucrats harassing customers and over invoicing them. One such was the short story, Upar Ki Kamai by the travel writer and Buddhist scholar Bhadant Anand Kausalyayan, in which the narrator's friend in a third class compartment comes to see the author in a second class compartment just before the train stops. The ticket checker asked the friend for extra fair because a ticket and the class do not match. Although the friend tries to explain that his belongings and seat are in the other compartment and that he has just come to look in on Kausalyayan, who is, I mean it's the first person narrator who assumes that he's the author as well. So the ticket checker will have none of this explanation. Upon arrival at the next station, the checker turns the friend over to the gate clerk, and the friend ends up having to pay both the ticket checker and the gate clerk for his alleged infraction.

In the second incident, the narrator decides to extend his ticket and get off at a further away station. To do so, he alights from the train temporarily at an immediate stop. However, the ticket clerk introduced delays and keep calming off his request to other clerks until he is almost out of time to get back on the train. He gives him the request, that sum and then gets back on the train. And at that point, right as this train is pulling out of the station, one of the clerks gives him a receipt and the revised ticket. However, when he looks at it, the receipt is for much less than the amount that he has paid. Using these methods, patient ticket clerks and inspectors make upar ki kamai. Top ups.

What does this mean for the anti-corruption apparatus? So after the ordinance responsible for creating the SPE lapsed, the interim government passes the Delhi Special Police Establishment Act of 1946. Now that act gives the government power to constitute a special police establishment in federal territories administered directly by the Indian government and it also transfers the SPE to the home ministry where its future incarnation continues to reside. Four years after that act, the Republican constitution gave the center with consent of the relevant state government power to extend the jurisdiction of the police from one state to another so you can conduct interstate investigations. The government also expanded the personnel and categories of crime dealt with by the anti-corruption unit. The prevention of Corruption Act of 1947 supplemented the Indian Penal Code and defined a new category of criminal misconduct in discharge of official duty. This included offenses relating to postwar reconstruction schemes, contract termination, and the disposal of government stores after the war. While the police remained a state subject in the 1935 act, the SPE now had a much wider set of responsibilities.

Crucially, three economic laws of wartime provenance that became pillars of the planned economy or planned economic life came under the SPE's purview. These were the commodity price controls, foreign exchange regulation and import and export control. The SPE increasingly focused its energies on related violations and became busier and busier. By 1960, it had 16 branches, a central investigating agency, a new enforcement wing to deal with breaches of import and export regulations and a fraud squad tasked primarily with handling violations of the New Company Act concerning joint stock companies. In 1963, the SPE investigated eight times as many cases as it had in 1945. Apart from the expansion of activities, there was also the beginnings of a new performativity related to a kind of having to account to the Indian people, as in franchise subjects and you can see in my very bad Photoshop skills, I've put a dotted line reaching out from the recipients to the trusters to suggest there's some kind of influence pressure. But it's dotted so it's like not that strong.

So this kind of connoted... Well, apart from doing more, the SPE also began to write monthly press releases, the director wrote monthly press releases and invited citizens to contribute leads about possibly wayward officials. And when these leads grew beyond what the SPE could handle, the home ministry created the administrative vigilance division to sort through them and adjudicate which ones to investigate. That's the sort of forerunner of today's Central Vigilance Commission. The Government of India began to do investigations into corruption to try to diagnose its nature and it created an improved metrics of its case convictions by tweaking its administrative procedures, for example, making bribe payers immune from penalty and therefore incentivizing into report and streamlining certain kinds of cases through summary trials.

However, it continued to be dogged by a few issues. First, it had to recruit from state forces like before, and provincial officials didn't like moving to other parts of the country, especially because the time spent in the SPE didn't necessarily help with promotions or building one's reputation locally. Second, it was risky for business people to speak up because of the high protection of officials and compromised future access to licenses and challenges in dealing with the state when trying to do business. And finally scarce staff as before meant inefficiency in dealing with complaints and an ever increasing roster of matters to handle.

So to take a step back again in this second stage, anti-corruption, the discourse and practice of corruption concerned the management of resources involving the planned economy and the emergence of a new class of public officials associated with this resource management. Corruption continued to be defined by the state specifically as bureaucratic and something to be eradicated. And there's no reason to think that in popular disclosure this was seriously contested. But practical constraints to total eradication emerged. We see a kind of path dependence here in so far as there were wartime antecedents to what takes place.

But as Rotem Geva has pointed out in the context of civil liberties in the dominion and early republican era, these are conscious choices that are made to retain or perpetuate old laws and procedures. We need not see continuity as something that comes from ignorance. We can also detect some change with respect to the state self-conscious attempt to give an account for its anti-corruption activity and solution citizen participation. Further, it tried to establish some metrics for its success, but as long as the political legitimacy, or as long as the political legitimacy of the ruling Indian National Congress party and its strategy of bureaucratic centralization was never seriously questioned, this policy broadly worked.

But things fall apart. So by the 1960s, the Indian economy began to lurch towards crisis. I think there's chapter in Francine Frankel's Indian Political Economy called Planning in Crisis. So here we are. So having stabilized the economy by the mid 1950s, India funded the second five year plans, which is 1956 to 1961, ambitious investment pattern to usher in heavy industry led import substituting industrialization, ISI. That process required even tighter bureaucratic control of resources and left consumer goods, sectors and agriculture behind. Second plan also relied on deficits that soaked inflation and was compounded by more food harvests. During the third plan period, 1961 to 1966, per capita income was flat and food inflation rose to over 13%. Government reports showed that income inequality over the previous 10 years had increased substantially. And by this time, fractional infighting had also beset the Congress, which had for the last two decades dominated the country's electoral landscape.

Developmental roles coincided with a discourse of corruption that created a kind of political pressure for changes in anti-corruption policy. In this third state, the discourse of corruption widened to comment not merely on wayward individual or bureaucrats or small groups of chums, but on abuses of powered by elected politicians acting in conjunction with vested interests. So the feminist writer Krishna Sobti's novella Yaaron Ke Yaar is a good example. Whereas Upar Ki Kamai had spoken specifically about a wayward ticket collector or a few of them, this short work uses the chit chat of an office of the central government to paint a picture of a system corrupted from clerk to minister. People get ahead by contacts, nobody plays by the rules, everyone is in it for themselves and advancement in the profession depends on patron client relationships. Bureaucrats authorized licenses for business and are quite literally compensated with food and women. Nepotism in government is endemic. So these novella appeared in the aftermath of well publicized ministerial corruption exposes. So her critique and others can be seen as part of a broader trend of citizen response under the conditions of enfranchisement or the logic of democracy. The other dynamic that compliments what Kaviraj called the logic of bureaucracy. Sometimes it is intention, sometimes it perpetuates.

Opposition parties seized upon cases like these to portray the Congress as corrupt and counter democratic. The right wing swatantra party, which I've spent last decade of my life studying coined a memorable term, permit and license raj, an oligarchy coalition of bureaucrats, Congress politicians and favorite business people who receive permits and licenses required for commercial activity. The bureaucrats are in the pocket of Congress politicians, they get bribes from the business people and the political parties in turn receive financial support from businesses. So the British raj is over, but the new raj of permit licenses, that is to hollow up the content of postcolonial democracy.

So how did the Congress and the state respond? So to have a few prongs, the first prong of the response is to launch investigations that are well publicized into ministerial conduct. The party also planned to have senior ministers resign to sort of stem the rock that had crept in after over a decade of empowered, so is the famous Kamraj plan. And you see some elected leaders who are found to been involved in family aggrandizement are pressured to leave office as pictured, Pratap Singh Kairon of Punjab has dubious distinction of being the first chief minister who leaves for corruption and Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad of Kashmir, who was said to have set up the BBC or the Bakshi Brothers Corporate.

Next, the Congress involved Ghandian ideas of self restrain and morality and the idea of citizenship as duty to solicit popular participation in anti corruption. This was a way of kind of signaling virtue. Towards this stand, the Home Minister, a Ghandian named Gulzarilal Nanda created a Samyukta Sadachar Samiti or United Association for Morality of volunteers from various social and religious organizations around the country. The organization imploded after opposition parties pointed out that the sitting home minister could not be in charge of it and that was the end of that. But finally, and more lastingly, the Congress launched administrative reforms. This involved selectively implementing the voluminous set of recommendations generated by an administrative reforms commission that sat for several years in 1960s. Apart from creating new more stringent laws, these measures included trying to streamline administrative processes so that they would prevent opportunities for abusive office. To go back to Foucault, governmentality evolves from being purely about punishment of crimes to also being about creating an environment in which you prevent.

The key institutional legacies of this period were the creation of the Central Vigilance Commission and the reconstitution of the Special Police Establishment as the Central Bureau of Investigation by home ministry resolution. The two were intended to compliment each other and ultimately be made independent statutory bodies. The CVC or Vigilance Commission is responsible for providing sanction for CBI investigations from complaints received and recommending prosecutions to the home ministry after the investigations were concluded. It also supplied departments of the various ministries with vigilance officers and oversaw punitive processes for non-criminal misdemeanors. At its head sat a central vigilance commissioner appointed for a fixed tenure and barred from subsequently holding public office. The CBI for its part, incorporated the Delhi Special Police Establishment and newly equated Economic Offenses and Food and Drug Offenses wings. It was awarded to sanction to investigate all public sector bodies.

Later developments would expose the Congress's response to be in some ways more performative than substantive. One issue was the non implementation of a number of salient measures recommended by the administrative reforms commission. For example, the Government of India never weakened public servant protections or created the promised Lokayukta or [inaudible 00:36:16] for the centers. Further, during this period, neither the CVC nor the CBI was made an independent statutory commission. So investigation of concerns pursued only when an appointee of the executive branch responsible to the home minister pursued them. And since 1965, as I mentioned in the beginning of the talk, the CBI has powers of investigation not merely over public servants, but in those matters for which it investigates crimes that also entangle the citizenry at large. Although the central vigilance commission was finally made independent in 2003, the CBI remains part of the home ministry.

So what can we say about this period? You see from our trusters fiduciary recipient handy dandy chart, the line from recipients to trusters is going a little bit thicker. The recipients, the Indian citizens and the truster fiduciary recipient relationships are now exerting a kind of political and electoral pressure upwards rather than the downward pressure applied by the executive. How exactly that place I'm not particularly invested in, but basically I'm just pointing out that political parties are dealing [inaudible 00:37:28], pushing. The discourse of corruption broadens to critique the system at large and the performative dimension of anti-corruption grows more powerful as a response.

But perversely it was done so in a way, in the case of the CBI in a way that the anti-corruption apparatus is later kind of turned on its citizenry and then corrupted itself. Governmental rationality at this stage evolves in a manner that there seems to be a tacit understanding that the anti-corruption body can really try to keep corruption within adequate limits rather than eradicated. So that's the kind of third stage in pocolian governmentality where we move from elimination to prevention to management of the activity within suitable limits.

So there's also a period when from the 1967 elections, Congress failed to form governments in 9 states and opposition parties did quite well paving the way for something that continues to this day where anti-corruption begins to have a political balance that exists for non Congress, often anti incumbent politicians. Key recent examples being Arwind Kejriwal and Narendra Modi.

So what do we make of all this? I want to make a few points in conclusion. The first is that adopting the status model created new truster fiduciary recipient relationships with more choke points for abuse of office, the template for which was World War II. Those wartime efforts created a kind of path dependence for what came later. An institutional continuity underpins anti-corruption efforts, but in response to changing rationales of emergency, war as emergency, integrity of the nation during the interim government and dominion period as emergency and then development as emergency. And finally anti-corruptions evolution from eliminate by punished to prevent to keep within manageable limits, to take the sort of pocolian framework takes place in a somewhat reflexive relationship to changing discourses of corruption and as anti-corruption politics start to take on democratic contours. But my own treatment is slightly different from the classic kind of pocolian case because the different stages are kind of contemporaneous, in that you have eliminate, prevent and keep within manageable limits kind of coexisting in different ways.

So to conclude, the politician J. B. Kripalani asserted in the constituent assembly that we must have a police state before having a welfare state. Such a state will be the surest foundation for a welfare state. As many scholars have shown, Colonial India was not quite a police state, but as Rotem Geva, Somnath Lahiri, the sole communist delegate to the constituent assembly, the fundamental rights were framed from the eyes of a police constable in his opinion. What I want to suggest is it would be perhaps surprising that the mechanisms of police power would prove so resilient as to resist decades of pressure for their dismantling in the post colony.

Why have I called this incomplete decolonization? What was so colonial about this? Well, the state adopted a colonial attitude and template by asserting this power, using colonial era emergency procedures over its citizens and ultimately making them all possible criminals. This was codified into a law in the colonial era, and it's not debated later on, despite its ability to be repressive of the citizenry and not adequately sensitive to their notional sovereignty. Speaks to the Janus face nature of the post-colonial state should one seeks to emancipate its citizens from the chains of the past and at times tighten them to prosecute its will. And I'd submit that it continues to persist in this particular instance because political leads find it useful. That's all. So thank you.

Sarath Pillai:

Thank you Aditya. Okay. We will get into questions right away. Amrita.

Amrita Kurian:

Hi Aditya. Thank you so much for this conversation. I mean, I work a little bit on this in contemporary India and so you've bought a lot of things that I'm still trying to process. But fundamentally, my question to you is, and this might sound a little, again, psychological, a lot of the idea of accountability and transparency post '60s and '70s comes from IMF and World Bank and the idea that post-colonial nations are not transparent enough. They're not good enough to be a democracy. A lot of what you are saying seems to suggest and which has also been written a little bit about at the moment of independence, India itself has its anxieties that it's a poor nation, is a nation of scarcity. Can you speak a little bit towards this idea of transparency that's currently in vogue? And the other question is, can you think of anti-corruption discourses that's prevalent in at the turn of independence to the moment right now as a sort of cry against the loss of hegemony of the ones who have traditional power, the ones who could sequester resources but now have to depend on the welfare state? I mean, not to undermine corruption as perpetuating structural inequality, but that's the way mostly poor people get resources, which is otherwise sequestered by people in power. Thank you so much for your talk.

Aditya Subramanian:

So, I think those are really important questions and I think the challenge is of course, trying to account for exactly what you say, which is the sort of fetishizing of accountability, transparency. I mean as Nayanika Mathur shows in her work, it is precisely these transparency processes that are the ones that arrest the policy from being executed. So I think a kind of skepticism about that is important, but at the same time I think it's a difficult, and ultimately you are looking at just the discourses that are produced by the state about itself and so that has to be read with that kind of critical attitude. So what I've tried here is to think about at the time, sort of restore it to the historical context in which it's read.

But I think that it would be a mistake to say that in the period that I'm looking at, that this is something that is purely driven or driven, especially from overseas interests. And I think in the 1960s you do have this whole, all over the world, you have administrative reforms committees, you have the United Nations decade of development and people in Malaysia are looking at India's corruption report and thinking about all of this sort of stuff happening. So I think that there are those global dynamics, but I think that they fit well with, or they kind of intersect with dynamics that are taking place within India. And I think that you're absolutely right. The discourse of corruption is often used by upper caste privileged elites. And even when we think of the Nehru era, they kind of look at the assertion of political power by people from other caste and class communities and certain kind of changing norms or whatever. No longer is polite English of the Queen spoken in the government office as symptomatic.

And so I think that's absolutely right and anti-corruption is also a way in politics, sort of period that I don't take up, I'm just kind of gesturing to, in which people who have got other kinds of political interests are using it as a code word to bring together a much more sinister agenda. I think we all know what I'm kind of talking about. So I think that is absolutely the case. But I guess in trying to historicize it, I want to think about, rather than get into the whole corruption and what it is thing, and I mean there's a lot of great theoretical work on this, is to think about the more limited problem as it's coming in here, but then again as you say, but not to keep it so disconnected that it looks like here's a history of the SPE from start to finish.

Sarath Pillai:

Shikhar.

Shikhar Singh:

Aditya, I had two questions for you. One was, you trace a history that culminates in what I see to be two organizations. One is the CVC, the other is the CBI. Are there any differential implications for the CVC as compared to the CBI in the emergence of this kind of narrative in the way it is set up or conceptualized? Because these are different bodies and have come under different use. And so one is the CVC, CBI comparison. The other is I think you abstract a way into a kind of colonial context. So has the experience of combating corruption through these kind of institutional tools been the same in some other colonies, even within the former colonies and within the sub subcontinent for example. And could you give us a comparative sense of how the Indian experience sits with say that in Pakistan or Bangladesh? Thank you.

Aditya Subramanian:

Thank you. Those are both really excellent questions. I mean I think the sort of key point is that the CVC, as I see it, traces its origins to the administrative vigilance division. I think it's all good to see it as kind of subservient and doing some of the leg work for CBI, sort of one without teeth and that one that does, I would say the first pass through the complaints and that sort of thing. And it's more about an organization for promoting good practice, whereas CBI is more right when crime has been committed, you go and you pursue the investigation. So that's the kind of distinction. And as a result, if you were to look at articles about the CBI versus the Central Vigilance Commission, you'll see that one is much more prominent the other and that nobody considered the great victory for anybody that when the CVC became independent. And to go back to Amrita's point, I think it's important to be sensitive to the fact that these are institutions that even if they have the most rigid setup, I'm conscious of this, the most rigid independent setup, they can very easily be kind of corrupted or whatever, misused.

The second point is regarding the sort of post colonial transitions. I mean this is something that I'd like to develop much further and part of it is questions of access and whatnot and that. I'm not particularly well schooled in the comparative method, but what I can definitely tell you is that there's a lot that parallels Malaysia and India and the sort of wartime transformation under the Japanese that Chris Bailey and Tim Harper have written about. And actually in the '60s, Syed Hussein Alatas who wrote the Myth of the Lazy Native was a contemporary of Edward Said, et cetera, wrote a number of influential works on corruption where he says that this all goes back to World War II and you see a lot of things taking place that are quite paralleled, very closely parallel what takes place in the Indian case without, of course, the sort of final stage, democratization, crisis of the state kind of thing because there you have a fairly different political process but they're also in that country interested in administrative reforms of the '60s.

Sarath Pillai:

Tariq.

Tariq Thachil:

Aditya, thanks so much for that talk and just thinking through the importance of understanding this specific history. You had quoted a couple of times Kavirajan. It was funny. There was an article of his in EPW that came out I think in the late '80s where he talked about the story of Indian politics can be told in two quite different ways. I think he says one is the story of structures and then one would be actual political actors and he says these are not at odds with each other, they can be mutually enforcing. But the reason I was thinking about that is that I thought while there was a lot that I kind of gleaned from your presentation, I did find it oddly unpeopled in some ways and you said at the end that was you're not particularly interested in highlighting individual biographies.

That said, I do wonder if the overall effect of the argument misses something by... I mean there's a lot of institutional path dependence here, which maybe the general point you want to make about, especially into wartime time moment. But it's a little bit hard to fully square that without some sense of the political incentives at play even within the... Were there other... When one bureaucracy is expanding its remit, potentially other bureaucracies are losing out on that. The story of a struggle of particular actors and alignments with people in political office. And because all of that bears very much even on how we understand the CBI today, I think it'll also give the piece a kind of wider readership. I don't know what stage of development it is now to bring at least some of that. And so I was wondering if you could reflect. If there were one or two, either kind of political moments or actors that you would like to inject or you think is very central to this story, who would they be? What would those moments be? I mean I'm putting you on the spot, maybe there's only one or two, but I do think it would in some ways add a lot to the breadth of the analysis to have that folded in some way, even if it's not central.

Aditya Subramanian:

So I think that's a really helpful advice. It is currently in the state of purgatory known as a revise and resubmit as I was telling. And one of the peer reviewer comments was that this reads a little too much inside baseball. So we don't know our peer reviewers, but inside baseball was, I imagine there's somewhere in this country because people in Britain wouldn't talk about baseball and certainly not in India. So I guess I would talk a little bit about a couple of people. I mean the first would be that very enthusiastic first director of the Special Police Establishment, Bambawale. And there's a case to be made that in those early years he kind of puts it on a really foreign footing because I think he's in charge of it for 10 years, which is a fairly long period of time.

And that's also an invitation I think to think about trying to recover certain kinds of private papers or at least trying to trace certain kinds of family networks because you might get some color to who are the kind of people involved in this space. And that also gives you a nice boil when you compare it to sort of Krishna Sobti's novella where there it's a lot of heavily swearing kind of people speaking in very particular kind of Hindi that would make someone blush, that sort of thing. And it gives you that sort of texture. And the other thing would be, I kind of dismissed it as kind of futile, but I think that the kinds of activities or kind of lengths through which Gulzarilal Nanda and these people went through and this samiti is quite interesting. Some of them were businessmen who went around making a pledge saying, "I will not pay a bribe." And there's not audio evidence of this, but I think that it's great and that would kind of enliven what I'm trying to present. So that's really helpful and those points are well taken and as I revise it, we'll definitely try to flesh that stuff out more.

Sarath Pillai:

So I'll jump in and ask a question myself. And both, I have two quick questions and both of them have to do with people as Tariq kind of took us there. I was thinking about CBI as an institution in contemporary India and most of the time, especially at local levels, CBI is seen as a less corrupt institution than a state government institution. For instance, when a sensitive crime happens in a state or something like that, there's a demand that state government refer the case to the CBI because there's a public trust in that institution, which most of the time state institutions lack. So I was wondering how does the public image of this institution as less corrupt would fit into this study that you're doing. Or that might not be true. I mean, I don't know whether there's a public perception that makes this institution less corrupt, but at least a state that I'm familiar with, which is Kerala, if you read the local news, there's always someone demanding that a case be given to CBI because the state government is going to mess it up.

And the second question is about the transitional period. And you talked a lot about governmentality and all of that is interesting and you also talked about Kaviraj and most of those post-colonial scholars who came in the wake of subaltern studies who studied this transitional period, one of the important things they talked about is the problem of legitimacy when you move from a colonial state which lacked absolute legitimacy in the eyes of the people because it was not representative or democratic. And by the '50s we have a democratic government. So people have written about whether is it a good thing to have satyagraha against a democratic state, for instance. How people reacted to the state in the colonial times as opposed to the post-colonial times. So I wonder when you talk about governmentality or this transitional time period, does the attitude of the people change in ways that are significant to the story? Thank you.

Aditya Subramanian:

So, two things. Yeah, Sarath, absolutely. I mean think those are both really great questions. I think the first is that I would say that I think whether it's the CBI being less corrupt or whether the fact that it's escalation we kind of have to think about. Yes, theoretically the Supreme Court should be less corrupt than the High Court, but is it also the fact that no, I'm going to get this, this is going to be, we are now gone from 5X to 10X and that's one question. But I think that there is definitely a lot that is done whether that is the way in which this publicity is handled in the early years, the fact that they produce these statistics of their conviction rates being high, there's all of that that goes on and it's an interesting thing to take apart that to produce this image of it is a body that actually works fairly well even though there's other evidence to the contrary that I've kind of discussed. So I think there's that.

And the other thing is that I also haven't offered you any comparison because of the limitations of my inquiry to the sort of state level anti corrupting body. So not so well placed to answer that. So on your question of governmentality, I mean I think we're thinking about the article of your supervisor, In the Name of Politics by the Dipesh Chakrabarty in public culture and I think the attitude of the people changing is important towards the state and what that is. And I think that's one of the reasons why in my kind of early state it was more about the hoarding trader and your problem with the British is the fact that they're there, not the fact that the colonial officer is whatever, extracting money. And yes, it's a problem collaterally in that they're colluding with the hoarders and whatnot, but you don't really care that the British war effort is being compromised because some contractors or whatever, there's some contract that's not being obeyed or being allocated in an unpleasant way broadly whereas in the later stages I think that at least in some circles yet I'm not making an argument that everybody [inaudible 00:59:33] franchise is now trying to hold the state accountable, but at least in some instance there's an idea that look, we expect a little more here.

And so there is that. It has more legitimacy but also more is kind of demanded of it. So there's that kind of dynamic as well.

Sarath Pillai:

So we are toward the end of the time, but we will take two questions together and you can answer them together as well. Kim.

Kim Fernandes:

Thanks so much, Sarath. And thank you very much Aditya for this excellent talk. I was actually curious since you used movies as examples and building off of Tariq's and Sarath's discussion of peopling this a little more, as you looked at other materials that talked about how corruption was seen or I guess thinking of movies, newspapers and archival materials that you may have come across in developing this history, what are some of the affective or other ways, people's responses to what corruption was, the thing of corruption itself, but also I guess in some ways the response to it. How did those change over time if at all?

Sarath Pillai:

Vqueeram, do you want to ask your question?

Vqueeram:

Thank you. Thanks Aditya for that. I just wanted maybe by way of this question greater clarity around this idea of development as emergency. So I'm just trying to understand is it that you're trying to suggest that there was, because in the way in which you seem to suggest there seems to be a large scale consensus on development as a project of social transformation. And so is this a legal emergency without actually any social precarity? And because were one to look at the idea of emergency from say other critiques of the development national project like say the Naxalbari, then this emergency takes on a very different perspective. And so I'm just trying to understand what exactly do you mean by this idea of development is emergency and emergency for whom? Emergency in the way in which the law kind of continues as a transformation in the colonial law or emergency as a set of practices that lead to creation of certain kinds of populations?

And that's for me where a rather kind of colonial legacy also continues because it's interesting that you speak about Foucault's governmentality without actually speaking about its productive capacity to create docility and discipline. So say, Tarangini Sriraman's work on petitions and identity documents in colonial India especially documents how the very time of wartime rationing creates the petitioning legal subject and it is the subject that then enters identity documents and legal documents and we see precisely this kind of desire for docility as the continuation of corruption. And so I'm just wondering if you want to speak also in terms of peopling this, also in terms of its idea of what its public or its population looks like. Thanks for that.

Aditya Subramanian:

So, those are both really excellent questions and comments. So thank you both, Kim and Vikram. And so I guess in terms of how does the discourse or the affect of corruption change, I think that at least and in the way that I'm seeing it, you start to see from the '50s, the '60s, the pivot is to one of more outrage and as something that kind flows through to more political pressure. With respect to Vikram's question about development as emergency, I'm kind using it and again, admittedly very kind of narrow way of thinking about the way in which sort of law that is devised for kind of temporary purposes under, for something like war is then actually recodified as something else that is taking place in kind of everyday life. But is because there it is seen to have a particular valance for something that is extremely important to continue and therefore needs to be that much stronger rather than the population controlled creation kind of imperative.

But I think as I expand this paper, this is something that I have to, very useful to think about particularly as you say to the reference to Tariq's question, which is what kind of population is it trying to create and thinking about the sort of life of the CBI who then is the kind of person, I guess the criminal subject or whatever, the criminal citizen who it is then kind of feeding into generating. So that's really helpful and something I'll kind of think about as I move forward.

Sarath Pillai:

Well, that brings to a close this seminar. I think we should all join and thank Aditya for giving this talk.

Aditya Subramanian:

Thank you all of you for hosting me and all of you for your wonderful questions.